ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am indebted to Professors Takahashi Makoto, Uehara Akira, and Liu Kang-Shih for their assistance in preparing this manuscript, and to Boye De Mente and Frank Hudachek for their invaluable editorial suggestions. I also wish to thank the Asia House for the research grant that made this book possible.

Torrance, CA 2008

AFTERWORD

In reading this book, you will have learned more than 400 kanji, and more than half of the pictographs the Chinese used to compose all of their kanji. With this knowledge you will already know the pictographic meanings of many hundreds more kanji that the Chinese formed from different combinations of the pictographs you have learned.

You will not, of course, know the pronunciation of a new kanji, nor its dictionary meaning, but knowing how the Chinese constructed the kanji will allow you to make a good guess at its meaning. Looking up the kanji in a dictionary should be enough in most cases to connect the meanings of the individual pictographs with the kanjis dictionary meaning. Flashcards and workbooks are available to help cement hard-to-remember kanji in your memory.

For example, the kanji is composed of the pictographs for mouth and bird . A good guess might be that it means the singing of a bird , and that would be correct. Looking up in a dictionary would show that it also means the chirping of an insect like a cricket or the cries of other animals.

The kanji is composed of the pictographs for mountain , cliff , and dry (the clothesline pole) . There are many possible guesses that you could make about the meaning of . All of them would have some basis, but the Chinese saw as the cliffs between the mountains and the water, on the dry side of the dividing line, and meant a riverbank or shore or coast .

To learn the approximately 2,000 kanji that appear in Japanese newspapers you will have to learn the meanings of less than 100 additional pictographs, since not all existing pictographs are used in those 2,000 kanji. Mastering the Japanese language will of course require full knowledge of grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation, for which there are many excellent texts and study guides available, but your present knowledge of the kanji and how they are put together will give you a strong headstart down that road.

APPENDIX A

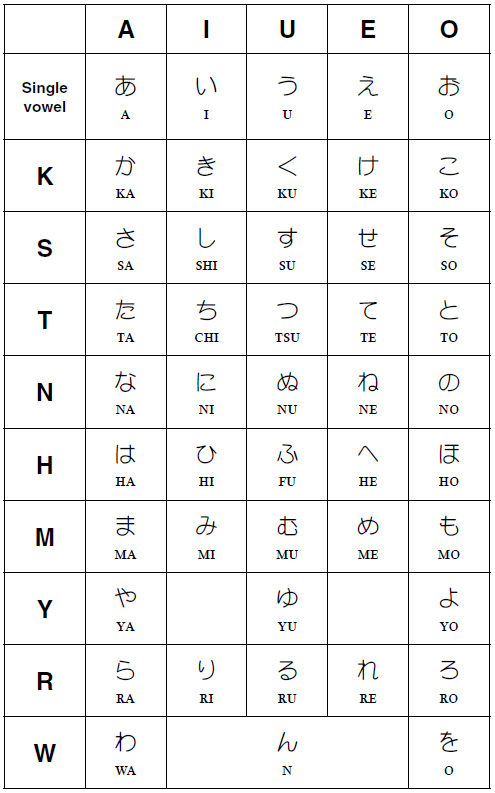

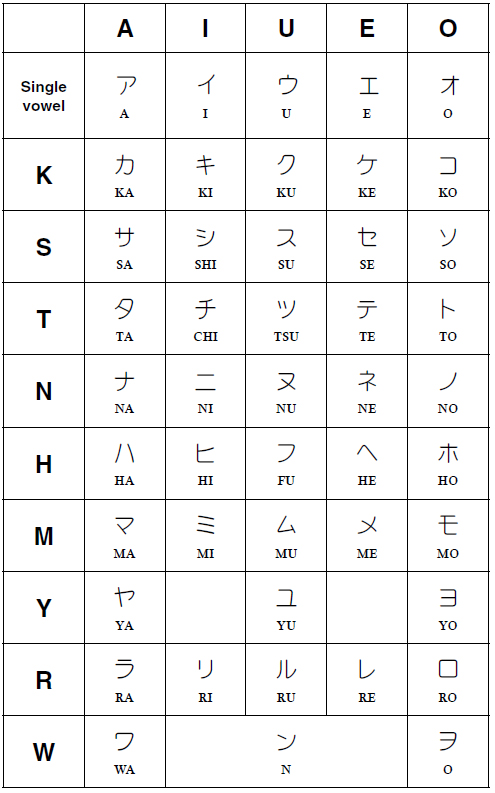

The Kana Syllabaries

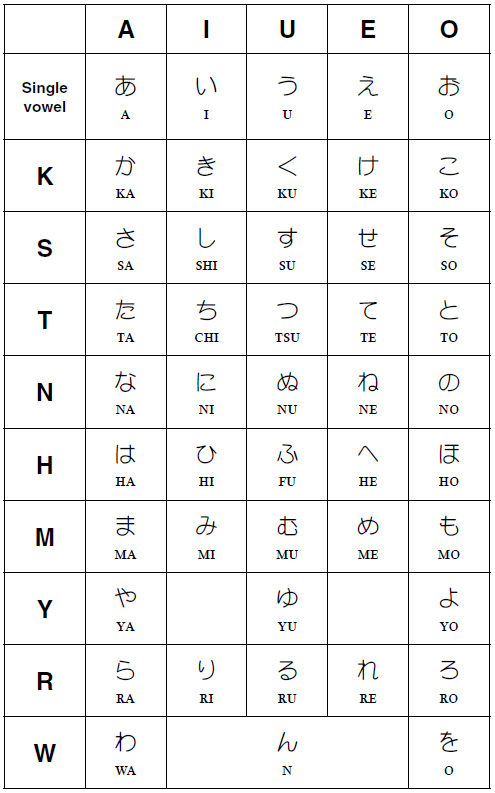

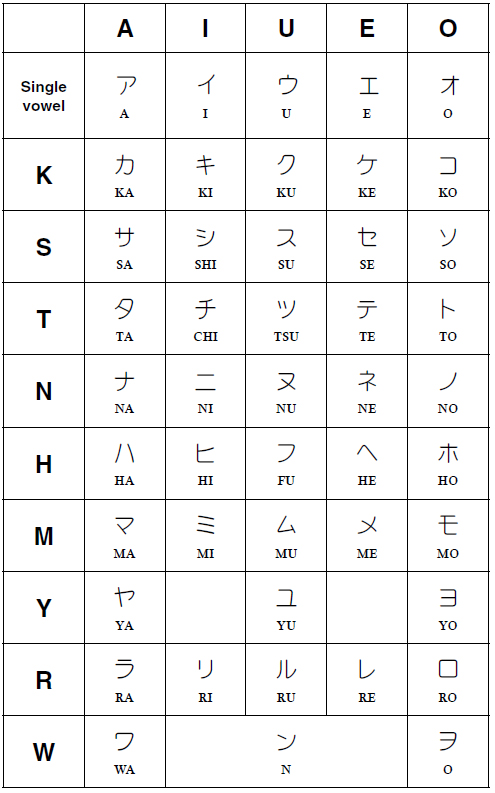

The Japanese writing system includes two sets of kana, each containing 46 characters. One set is called Hiragana and the other is called Katakana , and each set contains the same sounds as the other. As a general practice, the Hiragana are used to form grammatical word endings and the Katakana are used to write in Japanese the foreign loan words that the Japanese have borrowed.

Each kana is a syllable rather than a single letter, and most kana are combinations of one consonant and one vowel. These syllables are formed basically by adding each of the vowels A , I , U , E , and O to each of the consonants K , S , T , N , H , M , Y , R , and W . The A , I , U , E , and O sounds themselves and the N sound complete each set of kana.

Exceptions to this pattern are that the syllable SI is replaced by SHI , the syllable TI is replaced by CHI , and the syllable TU is replaced by TSU (the sounds SI , TI , and TU do not exist in Japanese). Also, the syllables YI , YE , WI , WU , and WE are no longer used.

In addition to the sounds that appear in the accompanying charts, other sounds are formed in one of two ways: by combining two or more kana to form one syllable, or by adding two small lines (called nigori ) or a small circle (called maru ) to certain of the kana to change their pronunciation slightly.

Examples of the first method are the adding of any of the single vowels to the end of a kana to form the long vowels, or the adding of the Y- syllables , , or to the I column syllables to form new syllables in the pattern KYA , KYU , or KYO . The syllable T is written , and the syllable KY is written .

An example of the second method is the forming of the syllables beginning with the consonants G , Z , D , B , and P . Adding nigori to the K -row forms the G -row:

This is the Hiragana chart:

This is the Katakana chart:

GA |

GI |

GU |

GE |

GO |

Adding nigori to the S -row forms the Z -row: |

ZA |

JI |

ZU |

ZE |

ZO |

Adding nigori to the T -row forms the D -row: |

DA |

JI |

ZU |

DE |

DO |

Adding nigori to the H -row forms the B -row: |

BA |

BI |

BU |

BE |

BO |

Adding maru to the H -row forms the P -row: |

PA |

PI |

PU |

PE |

PO |

To form the sounds JI and ZU, and are much more commonly used than or . The latter are used mainly in certain compound words.

Except for the formation of the long vowels, where a line is generally used rather than an extra vowel, these rules apply to katakana as well. In katakana , T is written .

APPENDIX B

Kanji Summary Table

| KANJI | PAGE

NO. | PRONUNCIATION

IN COMPOUNDS | PRONUNCIATION

BY ITSELF | ENGLISH MEANING | EXAMPLE

WORD |

| NICHI, JITSU | hi | Sun |

| MOKU | ki | Tree |

| HON, MOTO | hon, moto | Origin, source, book |

| MI | mada | Immature, not yet there |

| MATSU | sue | The end, extremity, tip |

| T | higashi | East |

| KY, KEI | Capital |

| DEN | ta, da | Rice field |

| RYOKU, RIKI | chikara | Strength, power |

| DAN | otoko | Man |

| JO | onna | Woman |

| MAI | imto | Younger sister |

| BO | oksan, haha | Mother |

| JIN | hito | Person |

| MAI, GOTO | Every |

| KY | yasumu | To rest |

| TAI | karada | Body |

| SHI | ko | Child |

| K | suki, suku, konomu | Love, like, goodness |

| TAI, DAI | kii | Big |

| TEN | ama | Heaven, sky |

| King |

| ZEN | mattaku | Complete, the whole |

| TAI, TA | futoi, futoru | Fat, very big |

| KO, SH | chiisai | Small |

| SH | sukoshi, sukunai | Few, little |

| RITSU | tatsu, tateru, tachi | To stand, to rise up |

| ICHI, HITOTSU | ichi, hitotsu | One |

| NI, FUTATSU | ni, futatsu | Two |

| SAN, MITSU | |

![Eriko Sato - My First Japanese Kanji Book: Learning kanji the fun and easy way! [Downloadable MP3 Audio Included]](/uploads/posts/book/406403/thumbs/eriko-sato-my-first-japanese-kanji-book-learning.jpg)