acknowledgments

M y garden is the foundation for my books, photography, and recipes. For nearly twelve months of the year, we toil to keep it beautiful and bountiful. Unlike most gardensas it is a photo studio and trial plotit must look glorious, be healthy, and produce for the kitchen. To complicate the maintenance, all the beds are changed at least twice a year. Needless to say, it is a large undertaking. For two decades a quartet of talented organic gardener/cooks have not only given it hundreds of hours of loving attention, but they have also been generous with their vast knowledge of plants. Together we have forged our concept of gardening and cooking, much of which I share with you in this series of garden cookbooks.

I wish to thank Wendy Krupnick for giving the garden such a strong foundation and Joe Queirolo for maintaining it for many years and lending it such a gentle and sure hand. For the last decade, Jody Main and Duncan Minalga have helped me expand my garden horizons. No matter how complex the project, they enthusiastically rise to the occasion. In the kitchen, I am most fortunate to have Gudi Riter, a very talented cook who developed many of her skills in Germany and France. I thank her for the help she provides as we create recipes and present them in all their glory. I want to thank Carole Saville, who over the years has generously shared her vast knowledge of unusual plants and exotic cooking techniques; her knowledge of edible flowers is in evidence throughout this book. Alice Waters, of Chez Panisse in Berkeley, California, is to be thanked not only for opening her garden to me and sharing her many ideas on edible flowers, but for the continual inspiration she gives all of us who honor fresh garden produce. Tribute also goes to Andrea Crawford for trialing many varieties of edible flowers for me and sharing her studied evaluation.

I thank Dayna Lane for her steady hand and editorial assistance. In addition to day-to-day compilations, she joins me on our constant search for the most effective organic pest controls, superior herb varieties, and best sources for plants.

I would also like to thank a large supporting cast: my husband, Robert, who gives such quality technical advice and loving support; Nancy Favier for her occasional help in the garden and office; two edible flower mavens who are always on hand to share their expertise and contribute recipes, Renee Shepherd of Renee's Garden and Cathy Barash, editor of Meredith Books; a triumvirate including Jane Whitfield, Linda Gunnarson, and David Humphrey, who were integral to the initial vision of this book; Kathryn Sky-Peck for providing the style and quality of the layout; and Marcie Hawthorne for the lovely drawings. Heartfelt thanks to Eric Oey and to the entire Periplus staff, especially Deane Norton, Jan Johnson, and Sonia MacNeil, for their help. Finally, I would like to thank my editor, Isabelle Bleecker, for her gentle guidance, attention to detail, and thoughtful presence.

appendix A planting and maintenance

C overed in this section are the basics of soil preparation, starting seeds, transplanting, fertilizing, composting, mulching, watering and irrigation, and maintaining most annual, perennial, and woody, edible flowering plants.

Edible flowers are produced by many types of plants. Some, like nasturtiums and calendulas, are annuals. Others, like daylilies, chrysanthemums, dianthus, and many of the flowering herbs, are perennials and hence stay in the garden for a number of years. There are also the "woody" plants, such as apple trees, redbuds, and citrus trees, which might live as long as 100 years. And then there are the roses, which while usually classified as a woody shrub, I put in a category by themselves, as they are such a quirky lot. Each type of plant needs its own planning and planting treatment, and maintenance techniques differ too. A number of these plants, like the citrus and pineapple guava, are quite tender; although they can be grown in a greenhouse, only planting them in the ground in a suitable climate is addressed here, since indoor growing is a science of its own and beyond the scope of this book. The seeds for some annual and perennial edible flowers may need to be started indoors weeks before setting them out in the garden. Refer to "Starting Seeds" for guidelines on starting your seeds early.

Trees and ShrubsThe Woody Plants

Planting

This section covers pineapple guava, elder-berry, redbud, lilac, lemon, orange, and apple trees. Since these plantings are permanent, you need to give a lot of thought to where you plant them. Will they get too large for the location? Is the soil in the area well drained? Is there enough sunlight in the chosen spot? Most woody plants need fast-draining soil and at least six hours of midday sun. Even though homeowners want to plant them in a lawn, they never grow very well surrounded by grass: they must compete for nutrients and water, are damaged by mowers and trimmers, and, if the lawn needs constant irrigation, they eventually develop a number of diseases.

Once you've decided on where to put your tree or shrub, it's time to plant. Woody plants are best planted in the spring when they are most available in nurseries and when they will have a long season to get established before winter cold sets in. Apple trees are available bare root, that is, when they are dormant and the roots are wrapped for protection, but without soil, or in containers. Other trees and shrubs are usually sold only in five-gallon containers.

To prepare the soil for your tree or shrub, dig a hole that is double the width of the root ball and six inches deeper. Mix in a cup or so of bonemeal around the bottom and rough up the sides of the hole with a spade or digging fork. Mix in half a wheelbarrowful of organic matter, but only if the soil is light and sandy. (Contrary to past recommendations to amend the planting hole in heavy soils with copious amounts of organic matter, we now know that the roots of woody plants seldom leave amended fluffy soil to venture out into dense native soils. Instead, they remain confined to the planting hole. When the soil is not ammended, the roots extend far into the parent soil.) Examine the root ball. Use a knife or sharp spade to cut through any thick mat of roots on the sides and bottom. Shovel some of the soil back in the hole and place the tree or shrub in the hole an inch or so higher than it was in the container. Straighten the roots out onto the backfill in the hole. Shovel the soil back in the hole and gently tamp the soil in place with your foot. Build up a small watering basin and water the plant in well by filling the basin full of water three or four times. Apply a mulch of organic matter at least three inches deep and at least six inches away from the trunk, to prevent the crown of the tree (where the bark meets the roots) from staying moist and possibly rotting. Keep the newly planted tree fairly moist for the first month and then start to taper off with the watering. In rainy climates water the tree if it rains less than once a week. In arid climates water deeply with at least one inch of water a week in hot weather. Drip irrigation is ideal for this purpose.

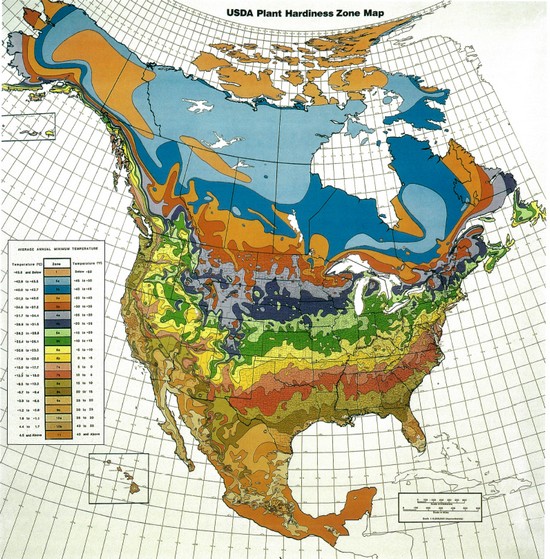

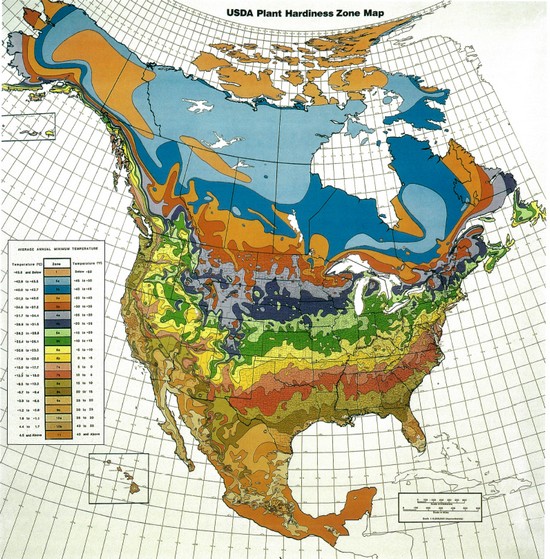

The USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map is most useful when you are growing perennial plants because it indicates how cold a given area will be during an average winter. In order to use the map, locate your geographical area and consult the color code that indicates which zone you are in. When you select plants for your garden, choose ones that grow in your zone. Remember, however, that the zone only indicates how cold your garden will get, but there are many other factors that affect the health of your plants, namely summer highs and your area's soil type.