Copyright 2010 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.

Published simultaneously in Canada.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4744. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permission.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic formats. For more information about Wiley products, visit our web site at www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Cell biology: a short course/ Stephen R. Bolsover ... [et al.]. 3rd ed.

Stephen R. Bolsover Elizabeth A. Shephard Hugh A. White Jeremy S. Hyams

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-470-52699-6 (pbk.)

1. Cytology. I. Bolsover, Stephen R., 1954

QH581.2.C425 2011

571.6dc22

2010040989

Preface

Our aim in previous editions of Cell Biology: A Short Course was to cover a wide area of cell biology in a form especially suitable for first-year undergraduates, keeping the book to a manageable size so that neither the content, the cost, nor the weight were too daunting for the student. We have remained true to this aim while thoroughly revising the book and introducing new sections on cancer and the immune system. Many more medical examples are included, and these concentrate on topics covered in medical courses rather than obscure genetic diseases.

The overall theme for the book is the cell as the unit of life. We begin (Chapters 13) by describing the components of the cell as seen under the microscope. We then (Chapters 48) turn to the central dogma of molecular biology and describe how DNA is used to make RNA, which in turn is used to make protein. The next section (Chapters 911) describes how proteins are delivered to the appropriate location inside or outside the cell, and how proteins perform their many functions. We then (Chapters 1214) describe how cells manipulate and use chemical and electrical energy. Chemical signaling within and between cells is covered in Chapters 15 and 16. The cytoskeleton is described in Chapter 17 and plays a major role in the phenomenon of cell division that, together with cell death, is

the subject of Chapter 18. Chapter 19, new in this edition, describes the immune system. Finally Chapter 20 uses the example of the common and severe genetic disease cystic fibrosis to illustrate many of the themes discussed earlier in the book.

Boxed material throughout the book is divided into examples that illustrate the topics covered in the main text, explanations of the medical relevance of the material, and in-depth discussions that extend the coverage beyond the content of the main text. Extended matching questions at the end of each chapter help readers assess how well they have assimilated and understood the material, while each chapter also poses a thought question that tests concepts rather than facts.

A comprehensive website accompanies the book at www.wileyshortcourse.com/cellbiology. As well as giving additional self-test questions, the website includes a wealth of extra examples, in-depth explanations, and medical discussions for which there was no room in the printed book. The site also provides links to other Internet resources together with references to primary research publications to allow readers to trace the origin of statements in the text. The symbol in the book indicates that a corresponding entry in the website can be consulted for more information.

Chapter 1

Cells and Tissues

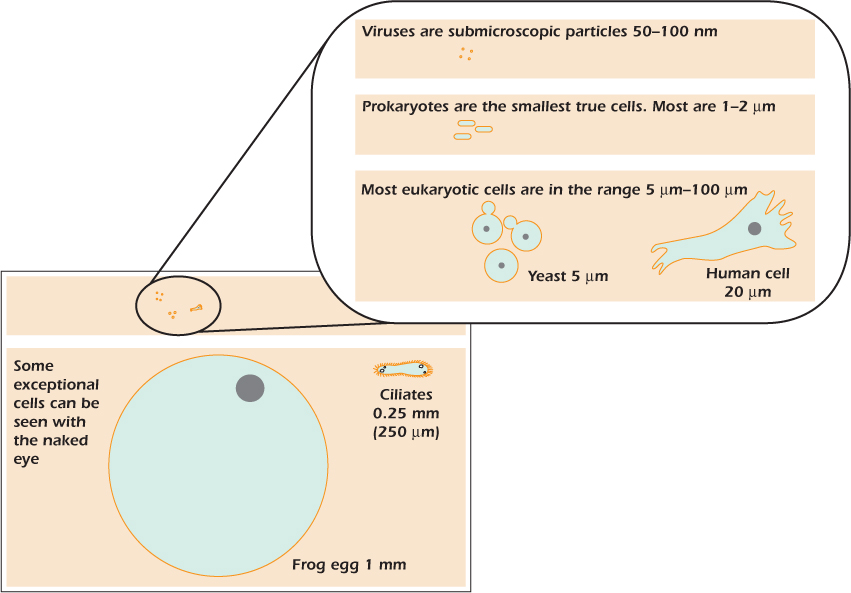

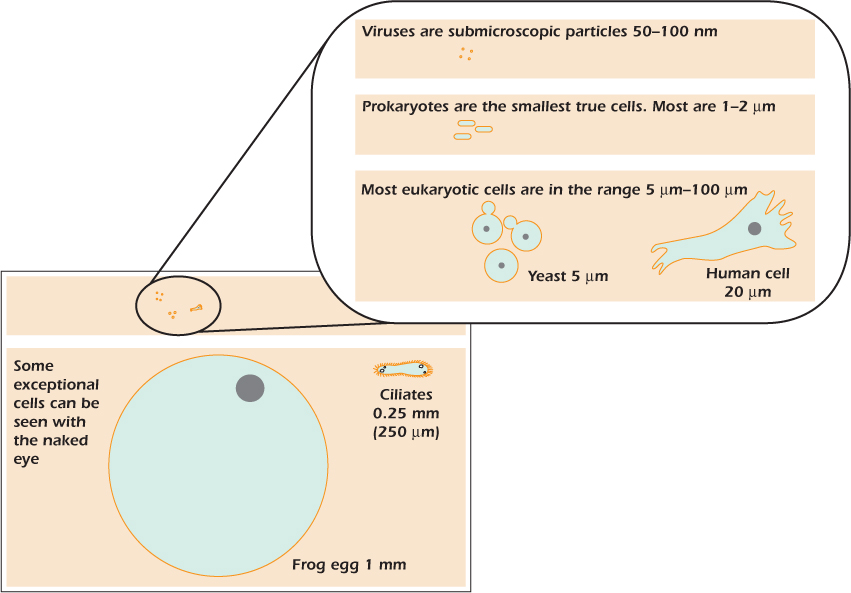

The cell is the basic unit of life. Microorganisms such as bacteria, yeast, and amoebae exist as single cells. By contrast, the adult human is made up of about 30 trillion cells (1 trillion = 10) which are mostly organized into collectives called tissues . Cells are, with a few notable exceptions, small () with dimensions measured in micrometers (m, 1m = 1/1000 mm) and their discovery stemmed from the conviction of a small group of seventeenth-century microscope makers that a new and undiscovered world lay beyond the limits of resolution of the human eye. These pioneers set in motion a science and an industry that continues to the present day.

Dimensions of some example cells. 1 mm = 10m; 1 m = 10m; 1 nm = 10m.

The first person to observe and record cells was Robert Hooke (16351703) who described the cella (open spaces) of plant tissues. But the colossus of this era of discovery was a Dutchman, Anton van Leeuwenhoek (16321723), a man with no scientific training but with unrivaled talents as both a microscope maker and as an observer and recorder of the microscopic living world. van Leeuwenhoek was a contemporary and friend of the Delft artist Johannes Vermeer (16321675) who pioneered the use of light and shade in art at the same time that van Leeuwenhoek was exploring the use of light to discover the microscopic world. Despite van Leeuwenhoek's efforts, which included the discovery of microorganisms and protozoa, red blood cells and spermatozoa, it was to be another 150 years before, in 1838, the botanist Matthias Schleiden and the zoologist Theodor Schwann formally proposed that all living organisms are composed of cells. Their cell theory, which nowadays seems so obvious, was a milestone in the development of modern biology. Nevertheless general acceptance took many years, in large part because the plasma membrane (), the membrane surrounding the cell that divides the living inside from the nonliving extracellular medium , is too thin to be seen using a light microscope.