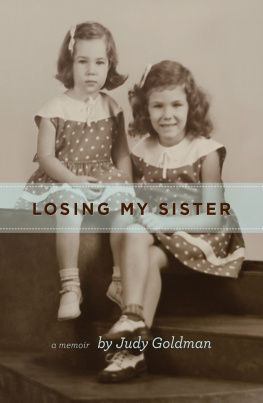

Preface

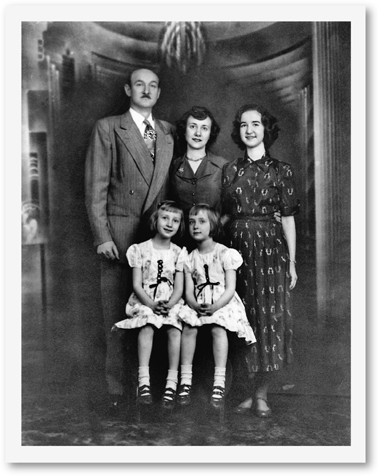

Visitors to my home always notice the framed black-and-white photograph of my family. Pointing to the two seated little girls identically dressed, they ask, Which one is you? I always respond, Guess! They guess right about half the time: Im on the right, my sister Mimi on the left. I love that people cant tell us apart, because in the photo Im six and shes eight. Then they usually ask about the three adults standing behind us. I explain, Thats my parents and my sister Naomi. Shes eight years older than I am. When they look more closely they see how much younger one of the standing women is than the other.

The question, Which one is you? is telling. Many sisters ask it of themselves. They can hardly think about who they are without thinking about how they are like or unlike their sisters. A sister is the person you might have been but arent, by choice or by chance.

The photo also dramatizes the enormous difference that a difference in age makes. A sister close in age is the one you played and fought with; an older sister can be much like a mother. And as with mothers, conversations with sisters can be some of the best and the worst conversations you ever have.

A word from a sister can make you laugh your head off, or giggle and be silly like when you were kids.

A word from a sister can send you into a tailspin because, as one woman put it, Shes part of my being, shes part of the fabric of who I am. So when theres disapproval, you feel it in a place that you dont feel it with other people.

Sisters dont even need words to feel it in that place; sometimes a look is enough.

You know Sadie doesnt approve of me sometimes, said Bessie Delany of her older sister. She frowns at me in her big-sister sort of way. When she said this, Bessie Delany was 101 while Sadie was 103. And Sadie said, I told Bessie that if she lives to 120, then Ill just have to live to 122 so I can take care of her. Sadie explained: The reason I am living is to keep her living.

The Delany sisters comments encapsulate the way sisters combine, in a uniquely intense way, two dynamics that drive all conversations and all relationships: connection and hierarchy. No one is closer than a sister who shares your family, your past, your memories. That connection is always there, whether you live together your whole lives, as the Delanys did, or see each other rarely or not at alleven if one has passed away. And sisters are also immutably arrayed by age, with resulting differences in influence and power that also endure, in obvious or subtle ways, throughout their lives. Those two dynamics, power and connection, work together and cant be pulled apart: The Delany sisters lifelong devotion was inseparable from the fact that one was younger and the other olderand therefore protective, and maybe a tad judgmental.

Sisters are inevitably compared to each other, because they are often together and, in any case, are thought of together. Each ones character or personality tends to be described in contrast to the others: the outgoing one and the shy one; the artist and the athlete; the smart one and the pretty one. And comparison is never far from competition. That too is built into the relationship, because sisters seek support and approval from the same adults, and it can often seem, whether its true or not, that love and attention given to one depletes whats available for the other. The same is true of brothers, and of sisters and brothers. Indeed, much of what I say about sisters applies to brothers too. I am certain that examples I give of sister conversations will remind many readers of their brothers and of other relationships.

Yet there is a particular texture and special complexity of conversations among sisters, because they are women. Women typically talk to their sisters more often than they talk to their brothers or than brothers talk to one another. Womens conversation is more likely to be about personal topicseither emotionally intense concerns or seemingly trivial details of their day-to-day lives. And talk itself typically plays a greater role in girls and womens relationships than it does in boys and mens. Because many women regard the sharing of personal information as a requirement of closeness, sisters often feel left out when they learn of secrets they were not told. But complications and hurt feelings can also result when secrets are revealed.

For all these reasons, conversation is an apt starting point to understandand improverelationships among sisters. And understanding conversations among sisters is a window into dynamics that drive all conversations and, hence, all relationships.

The language of conversation has been the focus of my research in linguistics, the study of language. For this book, in addition to analyzing transcripts of recorded conversations, I interviewed well over a hundred women about their sisterswomen whose ages spanned late teens to early nineties, and who came from a wide range of ethnic, regional, and cultural backgrounds. Most were American, but some were from other countries. Americans included Asian-Americans, African-Americans, Indian-, Italian-, Irish-, German-, and East-European-Jewish-Americans, and so on. They were straight, gay, Deaf, hearing, married, and single. I made a point of including women of these many backgrounds in order to hear a range of experiences. I did not attempt to compare one group with another or to generalize about any group. Readers should not assume that the women I refer to are white and European-American simply because I havent identified them otherwise. The chances are excellent that theyre not.

A woman told me that a friend, a guy, to whom she frequently talked about her sister, remarked, Gee, its like having a serious romantic relationship. He was right; it is. In the same spirit, a woman told me she has a good relationship with her sister but commented, We work on our relationship, like a marriage. She also said, in exasperation, Shouldnt there be some relationship in my life thats just easy