In memory of Helen Stuffins, a great inspiration and a great friend

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Susanna Wadeson, who decided that this books time had come, and the rest of the team at Transworld and Eden who also made it happen: Sarah Emsley, Mike Petty, Gavin Morris and Brenda Updegraff. Thank you too to Gillian Blease for the beautiful illustrations. Being a complete novice in so many of the subjects covered by the book, I have many experts to thank: Simon Saggers, whose beautiful smallholding is an inspiration and whose garden designs in this book will hopefully inspire others; Simon Fairlie for his expert advice on smallholding; Michael and Julia Guerra, who show how to create abundance from small spaces; John Chapple, a bee guru; Tony York for his pig expertise; and Caroline Muir for letting me get to know her urban chickens. Adrian Evans and Helen Stuffins were inspirational and instrumental in shaping my views on sustainability. Peter Harper from the Centre for Alternative Technology provided a pragmatic corrective to the less practical extremes of green thinking. Biologist David Perkins showed how beautiful biodiversity can be created in the most urban of spaces; Penney Poyzer and Gil Schalom demonstrated how a Victorian house can become an eco-home; and Will Anderson shared his experience of creating an eco-friendly house from scratch. Thanks are due, as always, to my agent Sappho Clissitt; and to my wife and sons, Fiona, Finn and Fergus, who were a source of joy and support throughout.

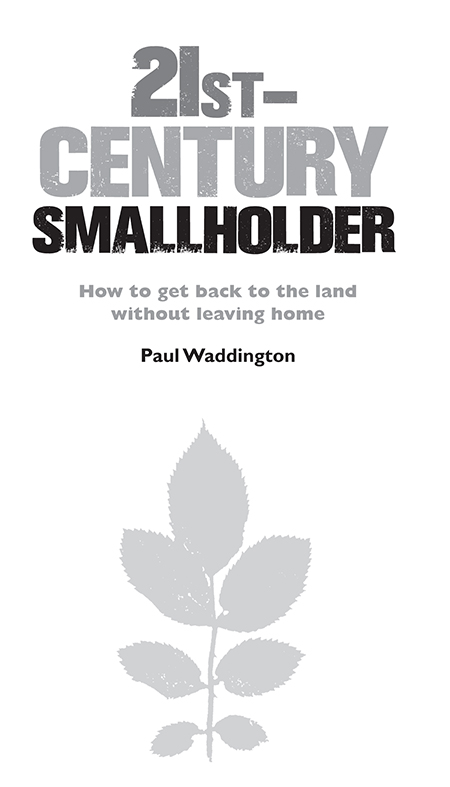

Who wants to be a 21st-Century Smallholder?

Many of us dream of four acres and freedom the idyllic, self-sufficient life in which we flee the city to live in harmony with the land, dependent on no-one. For all but a fortunate few, this is now an impossible dream. Absurd property prices have put four acres and a farmhouse out of reach of anyone lacking a six-figure sum of capital. Today, only the rich can afford to be peasants.

But a way of life that reduces our impact on the planet whilst also improving our quality of life has never been more sorely needed. Look at any aspect of modern living and theres a very good reason for doing things differently.

The food we eat now comes from a handful of gigantic retailers. Their demand for an uninterrupted, year-round supply of cosmetically perfect produce is turning our countryside into an agribusiness factory. Our food chain is now entirely dependent on fossil fuels: first, to manufacture the pesticides and artificial fertilizers without which industrial agriculture fails; and second, to power agricultural machinery and the enormous, road-based transport infrastructure that delivers food from farmer to warehouse to supermarket. As Felicity Lawrence points out in the food industry expos Not on the Label, just a few days without fuel would bring this countrys food supply to a standstill.

So the modern food chain is insecure. Its also killing us: polluting the environment with runoff and residues, decimating biodiversity and as we are now beginning to learn giving us produce that is depleted in the minerals and micronutrients that make it worth eating in the first place. Is a lettuce that is grown with artificial fertilizer, slathered with pesticides, then chilled and trucked around the place for a few days before spending a week in the fridge going to be as good as the one just picked from your garden? The evidence suggests not; and intuition screams it. Growing your own is more than just a nice idea.

Then theres the way we use energy and resources. Our homes are responsible for a third of Britains CO2 emissions. Almost all are highly dependent on energy sources that are not only insecure and nonrenewable but whose use is also the evidence is now overwhelming transforming our climate into something that could even become hostile to much of humanity in our lifetimes. It would take three planet Earths to support the entire worlds population living as the British do. Thinking about reducing energy and resource dependence is no longer the preserve of the thrifty smallholder; its something we could all benefit from, now and in the future.

Many of us dream of living differently because we can see what our Western lifestyles are doing to the environment. But I think we also aspire to peasantry because we instinctively feel that there is deep satisfaction to be gained from tasks that the consumer society would file under drudgery: growing and preserving food, animal husbandry, or managing your own water and energy resources. Our national fondness for gardening and pet ownership scorned by nations that are closer to their pre-industrial pasts surely points to a longing to be closer to nature. We have become de-skilled since we industrialized, losing our ability to live off the land. Today, that de-skilling has accelerated as our needs have become provided for by corporations. Even being a parent can be outsourced today. In a generation, weve forgotten how to grow things, fix things, even cook from scratch. And we are all having to relearn about what food is in season when. If society collapsed tomorrow, only Ray Mears would survive. Skills that were once effortlessly handed down from generation to generation now have to be learnt through piles of books, lengthy courses or painful trial and error. But as I have learnt its worth it. Few things beat the satisfaction of picking your own produce or knocking together your first beehive.

So perhaps we should all attempt to be self-sufficient at home in order to be healthy and happy and save the planet? I dont think so. Genuine self-sufficiency, in which you provide all your own material needs, is very, very tough. As the two case studies at the end of this book show, it requires a vast amount of learning, planning, investment and time, as well as a good-sized plot of land. If you had an immense garden, an iron will, accommodating neighbours and a complicit family, it might just be possible to emulate Tom and Barbara Good. Most of us arent like this, though. And even if it were practical, I doubt whether widespread self-sufficiency is really desirable. For a start, it would put out of business the small-scale farmers who are finding new outlets for seasonal, local and often organic produce through farmers markets and box schemes.

In between the Goods and the people who rampage from shopping mall to ready meal in a monster 4x4 is the 21st-Century Smallholder. You dont need four acres to be one; nor do you need vast amounts of capital and time. You wont be self-sufficient; but youll grow and do the things that suit your home and your life. If you have a small flat, then maybe your window boxes could keep you in salads and herbs. If you have a small garden, perhaps youll use part of it to grow gourmet fruit and veg that are best when just picked, and maybe have some chickens scratching around the place. And if youre fortunate enough to have a lot of outside space, then you may well be eating your own produce for much of the growing season; there might be bees... or even pigs. And wherever you live, you could be harvesting rainwater, making your own compost, saving even generating energy and turning your home into a wildlife haven.