CONTENTS

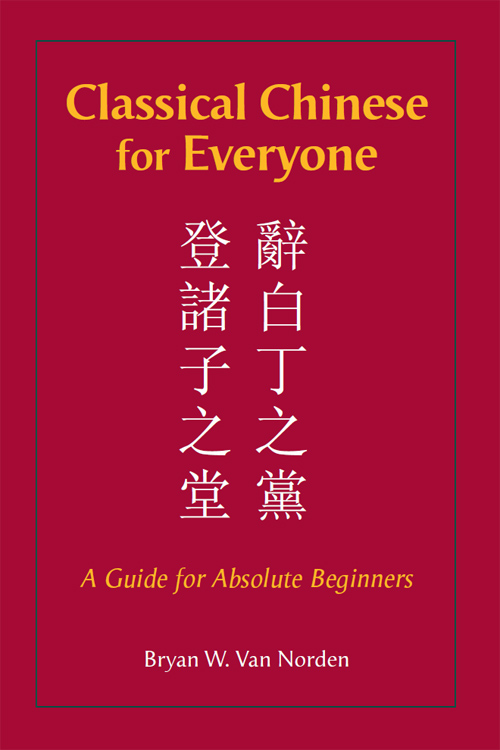

Classical Chinese for Everyone

A Guide for Absolute Beginners

Classical Chinese for Everyone

A Guide for Absolute Beginners

Bryan W. Van Norden

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

Indianapolis/Cambridge

Copyright 2019 by Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

22 21 20 19 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

For further information, please address

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

P.O. Box 44937

Indianapolis, Indiana 46244-0937

www.hackettpublishing.com

Cover design by Rick Todhunter

Interior design by E. L. Wilson

Composition by Aptara, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Van Norden, Bryan W. (Bryan William), author. Title: Classical Chinese for everyone : a guide for absolute beginners / Bryan W. Van Norden.

Description: Indianapolis : Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., [2019] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019010488 | ISBN 9781624668227 (cloth) | ISBN 9781624668210 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Chinese languageTextbooks for foreign speakersEnglish.

Classification: LCC PL1129.E5 V36 2019 | DDC 495.182/421dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019010488

ePub3 ISBN: 978-1-62466-864-7

Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy , Second Edition. Edited by Philip J. Ivanhoe and Bryan W. Van Norden.

Bryan W. Van Norden, Introduction to Classical Chinese Philosophy .

Mengzi, The Essential Mengzi: Selected Passages with Traditional Commentary . Translated, with Introduction and Notes, by Bryan W. Van Norden.

Confucius, The Essential Analects: Selected Passages with Traditional Commentary . Translated, with Introduction, by Edward Slingerland.

Sun Tzu, Master Sun's Art of War . Translated, with Introduction, by Philip J. Ivanhoe.

Lao-Tzu, Tao Te Ching . Translated by Stephen Addiss and Stanley Lombardo. Introduction by Burton Watson. With Ink Drawings by Stephen Addiss.

Contents

The page numbers in curly braces {} correspond to the print edition of this title.

{xi} Preface

This book is designed to introduce Classical Chinese to students with no previous exposure to Modern Chinese. This differs from the approach used in most textbooks, which assumes you already have studied Chinese for at least a couple of years. (Some of these books also seem to assume that you plan on being a Sinologist and already have a masters degree in linguistics!)

I started studying Classical Chinese as an undergraduate (with Nathan Sivin at the University of Pennsylvania), after completing three years of Modern Chinese (studying under Victor Mair and the late A. Ronald Walton, among others). I continued my study as a graduate student in philosophy at Stanford, and translation has been an important part of my research and publications ever since. However, I learned from my teacher, the late David S. Nivison, that it is possible to teach Classical Chinese to students with no previous exposure to the language; he routinely included language instruction as part of his introductory course on ancient Chinese philosophy. Later, I was one of the founders of the Department of Chinese and Japanese at Vassar College, and I offered our first course in Classical Chinese. In the first years of the program, we simply did not have enough students to make two years of Modern Chinese a requirement for Classical Chinese. Consequently, I wrote the first draft of this textbook for our students. The Department of Chinese and Japanese at Vassar has flourished, and I now use Paul Rouzers A New Practical Primer of Literary Chinese to teach students who have already learned Modern Chinese.

I still got some use out of my old textbook, though, sending PDFs to Western-trained philosophers and interested amateurs when they asked for a recommendation for a text to help them learn at least a little of the language of the classics of Confucianism and Daoism. On a whim, I {xii} submitted the manuscript to my editor at Hackett Publishing Company, Rick Todhunter, and he reported that there is a real hunger for a book like this.

So I owe a debt to my own teachers, to my students, and to my colleagues at Vassar, all of whom were essential for the eventual completion of this book. I am also grateful to my colleagues at Yale-NUS College, Scott Cook and Jing Hu, for assistance on some technical issues. Justin Tiwald and four anonymous referees also provided invaluable feedback and corrections to earlier drafts. Rick Todhunter has been very encouraging of this project from the beginning. In addition, Hacketts production director, Liz Wilson, and this books copyeditor, Shannon Cunningham, and its proofreader, Leslie Connor, have made me sound much more articulate than I am. None of these people is responsible for my mistakes, of course.

{xiii}

Classical Chinese is the form of Chinese that was written in the period between roughly 500 BCE and 220 CE. It is the language of classical Confucianism and Daoism. This book is designed to introduce you to the fundamentals of Classical Chinese grammar, some basic vocabulary, and fundamental skills in using a dictionary and classical commentaries. After reading this book, you will still have a lot to learn. However, you should be ready to continue learning from a more conventional textbook. In addition, with perseverance and the help of a good grammar and dictionary, you will be able to work your way through a few elementary Chinese texts on your own.

Two aspects of this book are distinctive. First, most other textbooks of Classical Chinese assume that you have already completed at least two years of Modern Chinese or Japanese. However, this textbook assumes no previous familiarity with the Chinese or Japanese spoken or written languages. Second, from the very first lesson, this book teaches you using selections from actual Chinese philosophical texts. These include readings from the sayings of Confucius, Laozi (the legendary founder of Daoism), and some Tang dynasty poetry. In three lessons I edited the text slightly, but all of the other readings are complete, and none of the readings are artificial or dumbed down.

Classical Chinese is a style of Literary Chinese, the written language used by the educated in China for approximately 2,500 years. It was also adopted as the literary language of premodern Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. In a way, Literary Chinese played a role in East Asia similar to Latin in the West. Latin and Literary Chinese were originally the written form {xiv} of the language spoken natively by a particular group of people. However, the ordinary vernacular language evolved into various spoken dialects, and Latin and Literary Chinese became the common written languages of the educated elites. In the West, books were first printed using vernacular English, German, etc. during the Protestant Reformation (beginning in the sixteenth century), but educated people were expected to know Latin until the beginning of the twentieth century. In China, almost all texts were printed in Literary Chinese until the New Culture movement of the early twentieth century.

Everyone knows that there is something distinctive about the Chinese writing system, but there is considerable ignorance and confusion about how that writing system works. We can illustrate four of these five types using symbols that are familiar to contemporary English readers.

{xv} Pictograms were originally drawings of something: