THE OCEANS

THE OCEANS

A Deep History

EELCO J. ROHLING

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2017 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-16891-3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016960241

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Gotham XNarrow & Sabon Next LT Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For Mark and Sander ,

and all others who were denied a future .

May all recipients of that greatest gift

safeguard it for future generations .

CONTENTS

THE OCEANS

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

You may have been told that we know more about the Moon than about the oceans. It is a claim that I often hear from public relations staff, teachers, schoolchildren, and many others in casual chat at parties or receptions. But I work on ocean science for a living, and I am not convinced that its true. Instead, it strikes me as evidence that most people have no real idea of how much we actually do know about the oceans.

I have been researching and teaching about the oceans for 30 years in the field of paleoceanography. In plain words, paleoceanography studies the ancient oceans and their changes through geologic time, before historical records. In practice it is interpreted to include the associated climate changes because there is a close interaction between the oceans and climateyou cannot research one and not the other. Well over 1000 researchers are currently active in this field worldwide. The number is several times larger if we include the wider ocean sciences, and especially if we include naval research as well. Although this still may not make it a large community, it has been remarkably productive in deciphering the natural, underlying rhythms and processes of ocean and climate change, against which humanitys impacts can be assessed.

A sound general awareness of this knowledge is essential to a well-rounded understanding of the Earth. As such, it is necessary to any meaningful discussion about matters of conservation and policy definition, andindeedto underpin election of knowledgeable government representatives. The apparent lack of such awareness can only mean that my colleagues and I have fallen short; that we have insufficiently communicated our findings beyond the narrow circle of specialists. With this book, I hope to change that.

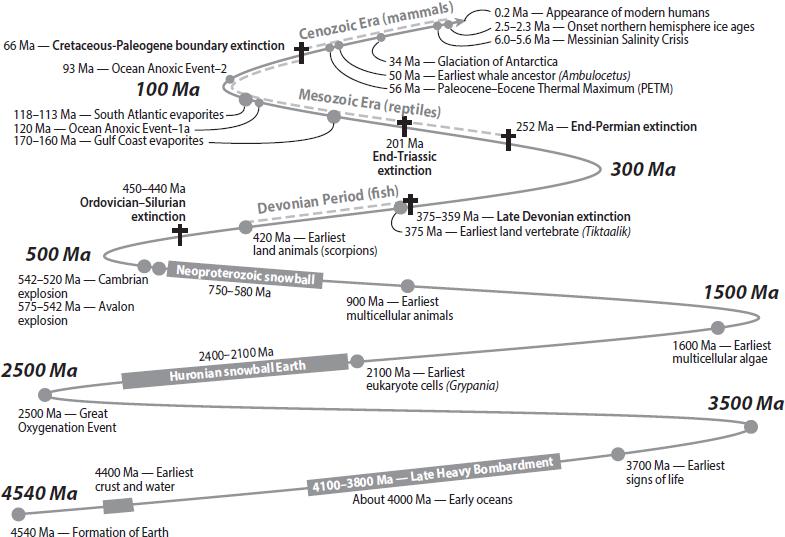

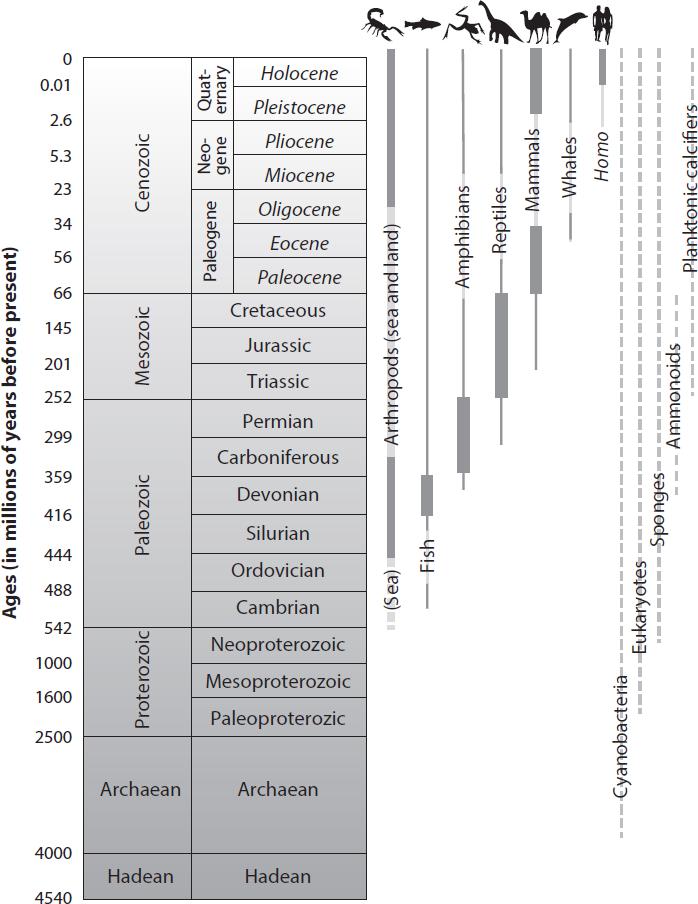

Figure 1. Timeline of events as discussed in this book. For a more formal representation of the geologic time scale, see . Ma stands for millions of years ago.

I venture here outside my scientific comfort zone, aiming to share our understanding of how the oceans have come to be the way they are today. Thus, I aim to offer a foundation upon which you, the reader, can build your own informed opinions about the challenges resulting from humanitys relentless drive to exploit the world ocean and its resources. To achieve this, we will travel through time from the first development of oceans more than four billion (or 4000 million) years ago, to the present. Along the way, we will stop at some of the most remarkable events and developments of life in ocean and Earth history.

We will see that life on Earth, including humanity, is closely intertwined with changes in the oceans and climate, no matter whether these result from natural variability or human impacts. These intricate connections between the oceans, climate, and life have been shaped and refined over four billion years. But we will also see that abrupt and dramatic adjustments which have taken place within this complex network, and may take place again, and that highly developed organisms seem to suffer the consequences most intensely. The explosive growth of humanity and our ever-increasing resource dependence make us especially vulnerable.

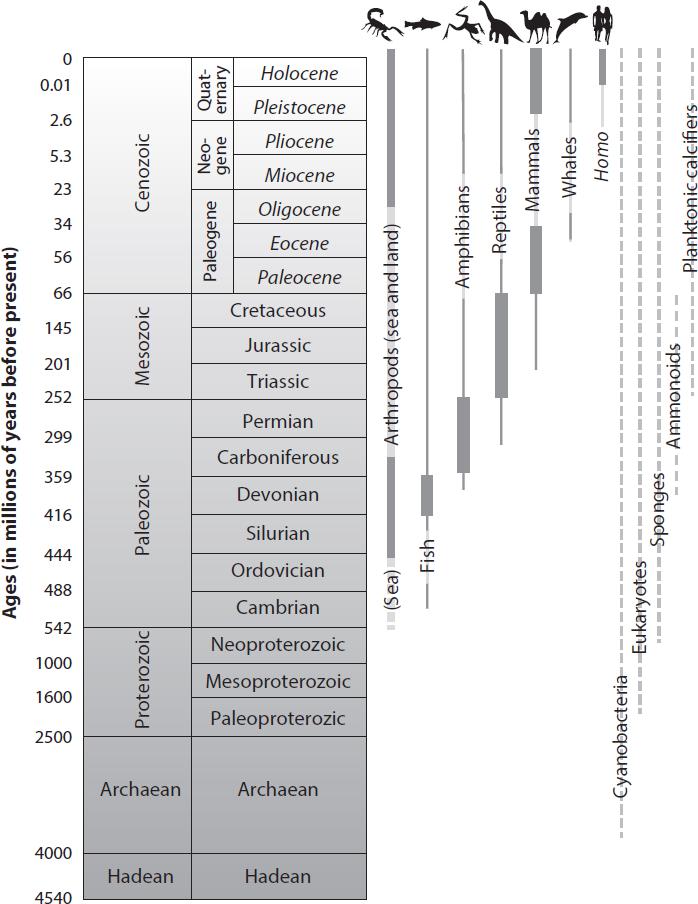

Figure 2. Geologic time scale with time ranges of major organisms discussed in this book. Left column , ages in millions of years ago. Note that the scale is nonlinear, for presentation purposes. From 4540 to 542 Ma, the left-hand gray column gives geologic eons and the right-hand gray column geologic eras. More detail is needed for the Phanerozoic eon, which spans from 542 to 0 Ma, so for that time the left-hand gray column gives geologic eras, and the right-hand gray column geologic periods ( regular font ) and relevant epochs ( italics ). Homo is written in italics as it refers to a specific genus. Bars indicate time ranges, with a continuous thin or dashed line for total range of named groups, and with thicker lines for periods of relative dominance. The arthropodswhich include scorpions, spiders, millipedes, centipedes, insects, trilobites, crabs, lobsters, crayfish, krill, shrimp, woodlice, ticks, mites, etc.have always been immensely numerous. Today, roughly three-quarters of all known animal species are arthropods.

To gauge the potential consequences, we need to understand the natural variability that underlies human impacts. To learn about natural variability, all we can do is study the past before humans became important. To appreciate the scale and rapidity of human impacts, we need to compare and contrast them with a sound understanding of the underlying natural processes. Without the background knowledge, all else is conjecture. With the background, we stand prepared to make knowledgeable decisions for sustainable actions that will both give us what we need and preserve the system for posterity.

It wont surprise anyone who regularly watches the news that humanitys impacts on the oceans are multifaceted and profound. We pollute the oceans with medium- to long-lasting materials such as plastics, netting, radioactive waste, and dumps or wreckage laden with petroleum or chemicals. We disturb their food webs by overfishing, and by harmful fishing practices such as bottom-disturbing trawling and fishing with explosives. We overfeed (eutrophicate) them by pumping unnaturally large amounts of nutrients into their ecosystems by way of agricultural runoff, effluents, and detergents. We acidify them with our massive fossil-fuel-based carbon injection. And we cause unprecedentedly fast warming with our greenhouse-gas emissions, mainly in the form of carbon dioxide (CO ) and methane (CH ).

We have allowed all this to happen because of a deep-seated, historical notion that the world ocean and its resources are limitless, despite frequent warnings from modern scientific assessments that this is a serious mistake. Probably the worst part of it is the rapid acceleration of the problems. Some 500 years ago, the oceans still were pretty much pristine. By and large, they suffered only moderate change until the early 1800s, by which time the worlds human population had reached one billion. Then things changed: large-scale whaling developed from about 1820, and global fish capture started to rise (today, it is well over 10 times higher than in the early 1800s). In the last two centuries, overfishing, pollution, eutrophication, acidification, and warming have risen sharply, on the back of fast human population rise, industrialization, globalization, and consumerism.