FOREWORD DAVID HARRIS

T

he herbarium at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE) houses more

than three million specimens of dried plants collected from all over the world,

covering a period of over three hundred years. And it continues to growwe are

currently adding new specimens, collected by our staff, students, and international

colleagues, at a rate of about ten thousand per year.

Throughout its long history, scientists have used the RBGE herbarium collection

to help them interpret the diversity of plants and fungi. Crops, poisonous plants, garden

plants, medicinal plants, tiny herbs, giant rain-forest treesall kinds of plants and fungi

can be found here. Herbaria such as the one in Edinburgh, by acting as libraries of

plant material, have been crucial in helping us to determine which plants grow where

and how we can differentiate them.

The scientific documentation of the natural history of the world started as

part of the Enlightenment project in the eighteenth century. In Scotland, botanists

had almost all been men, while women and people from other countries who were

involved in the work very rarely had their contributions recorded on the labels or in the

literature. In parallel, there are items in the herbarium that reflect a historical, colonial

approach to the global exploration, acquisition, and exploitation of the worlds natural

resources. It is key that we remain aware of the circumstances in which some specimens

were collected; at the same time, it is critically important that the valuable resources

within the collections are available and used as a global resource. Although our modern

botanical community is very different from how it was three hundred years ago, it is

only by acknowledging the past that we are able to continue to push for more respect

and inclusion.

Now, faced with the twin challenges of climate change and the biodiversity crisis,

researchers are using herbarium specimens in new ways to understand and address

these threats to our planet. For example, old herbarium specimens from Scotland, which

pre-date the Industrial Revolution, provide a snapshot of the environment before

human activities started to have a major impact on it. Plants absorb pollutants from

air and water, and these can remain in the dried specimens. Therefore, by analyzing

herbarium specimens, we can track rises and falls in levels of pollutants from a time

when they were hardly produced. To give another example, by examining herbarium

records of the time of first flowering over two hundred years, we can track plants

response to changing global temperatures. We can also use herbarium records to

track plant migration, and use the information to predict how plants will respond to

climate change in the future.

Over the past ten years, we have digitized a sixth of the collection by capturing

high-resolution technical images of the specimens, each accompanied by a ruler (for

scale) and a color chart, and making them freely available on the Internet. This has

enabled researchers from anywhere in the world to virtually examine the physical

material held in the cupboards here in Edinburgh, and to download the images and

relevant collection data. This is one of a number of international programs that allow

access to the information needed by those working to halt biodiversity loss.

Information from herbarium specimens is used to help determine the

conservation status of plant species, which are included in the International

Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species . This is an

essential source of information on the extinction risk of individual plant, animal,

and fungus species, and as such, informs global efforts to conserve biodiversity.

Based on comprehensive assessments of wild populations, thousands of plants have

been assigned to categories such as Vulnerable or Endangered, or, in the worst cases,

Extinct.

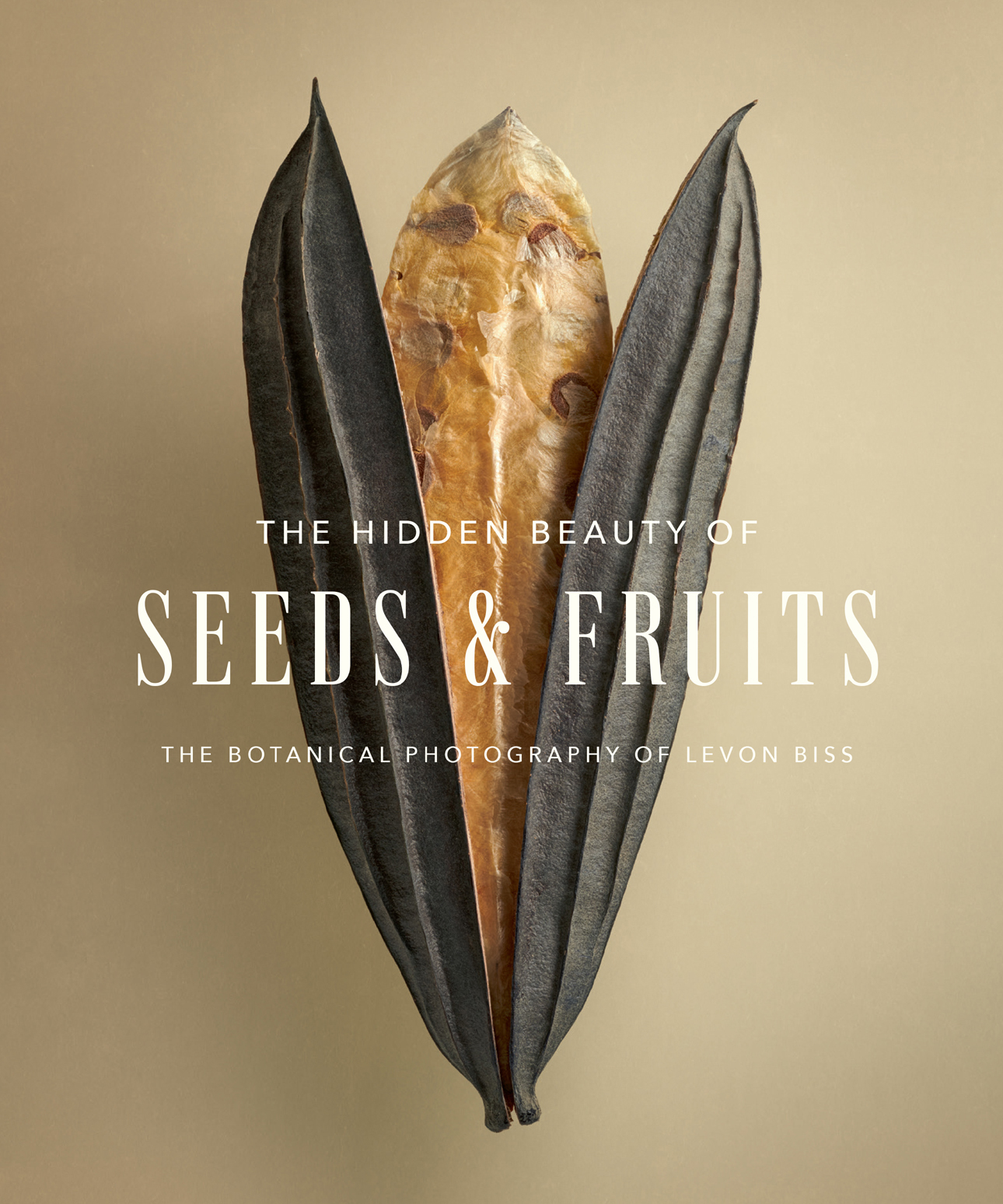

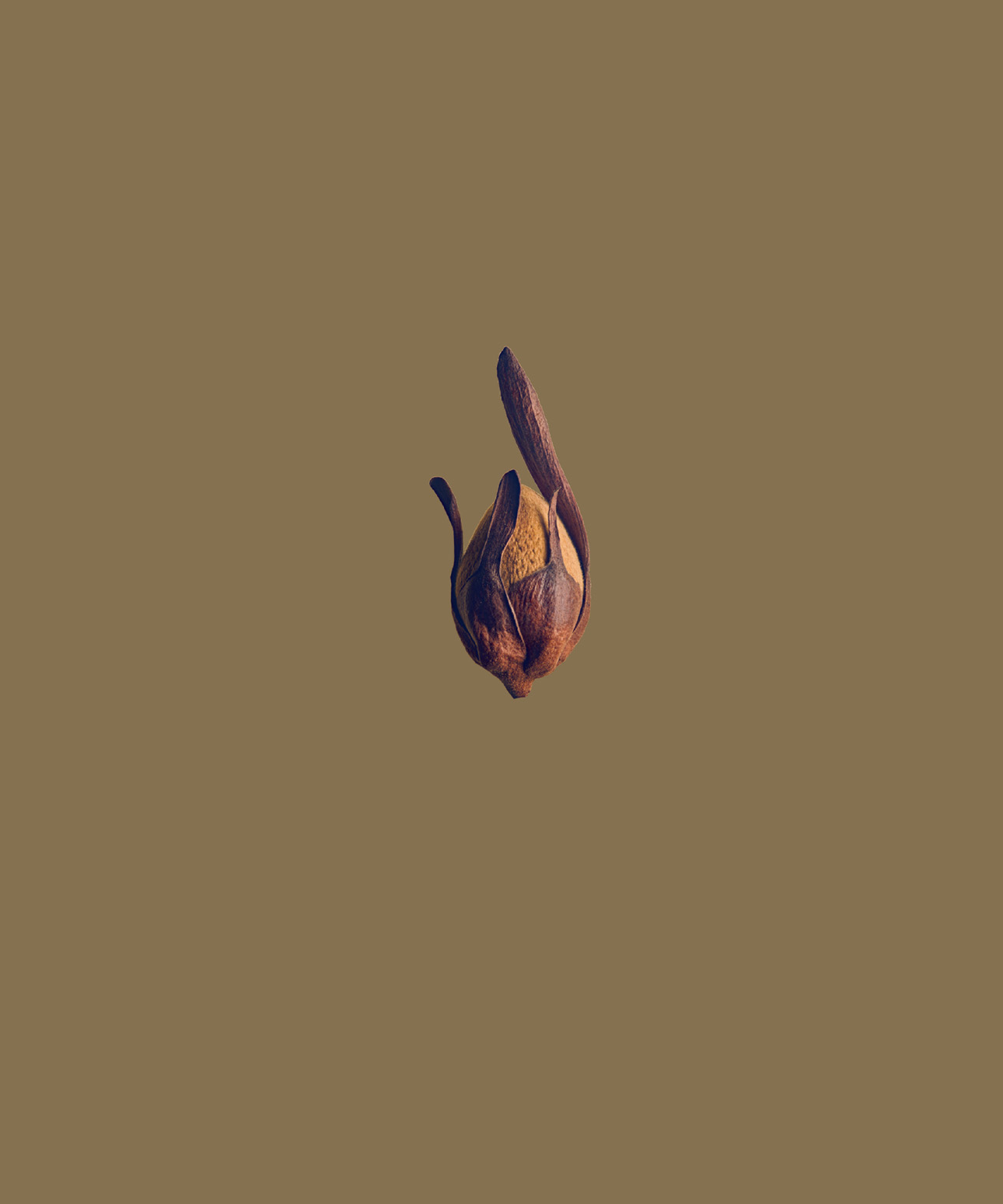

Most herbarium specimens have been pressed flat and affixed to a standard-

size piece of card called an herbarium sheet. Once the specimen has been prepared,

the sheet is placed in a folder. Multiple folders are then stored flat on shelves in

specially designed cupboards. Some specimens, however, are too bulky to fit on

an herbarium sheet; instead, they are stored in boxes and bags of different sizes.

Together, these specimens are called the carpological collection, because they consist

almost entirely of fruits and seeds.

When I visited the Microsculpture exhibition at Inverleith House Gallery last

year, I was struck by the intensity of the jewel-like hues of the insect portraits of

Levon Biss. Therefore, when the possibility of interesting him in taking photographs

of the carpological collection was suggested, I was unsure whether he would find

enough color in the specimens, despite their huge variety of form. However, when he

first visited the herbarium and took his first tour of the carpological collection, we

realized that this idea could come to fruition.