Analysis and evaluation are recognized as crucial skills for all students to master. And for good reason. These skills are required in learning any significant body of content in a non-trivial way. Students are commonly asked to analyze poems, mathematical formulas, biological systems, chapters in textbooks, concepts and ideas, essays, novels, and articlesjust to name a few. Yet how many students can explain what analysis requires? How many have a clear conception of how to think it through? Which of our graduates could complete the sentence: Whenever I am asked to analyze something, I use the following framework:...

The painful fact is that few students have been taught how to analyze. Hence, when they are asked to analyze something scientific, historical, literary, or mathematicallet alone something ethical, political, or personalthey lack a framework to empower them in the task. They muddle through their assignment with only the vaguest sense of what analysis requires. They have no idea how sound analysis can lead the way to sound evaluation and assessment. Of course, students are not alone. Many adults are similarly confused about analysis and assessment as intellectual processes.

Yet what would we think of an auto mechanic who said, Ill do my best to fix your car, but frankly Ive never understood the parts of the engine, or of a grammarian who said, Sorry, but I have always been confused about how to identify the parts of speech. Clearly, students should not be asked to do analysis if they do not have a clear model, and the requisite foundations, for the doing of it. Similarly, we should not ask students to engage in assessment if they have no standards upon which to base their assessment. Subjective reaction should not be confused with objective evaluation.

To the extent that students internalize this framework through practice, they put themselves in a much better position to begin to think historically (in their history classes), mathematically (in their math classes), scientifically (in their science classes), and therefore more skillfully (in all of their classes). When this model is internalized, students become better students because they acquire a powerful system-analyzing-system.

This thinkers guide is a companion to The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools. It supports, and is supported by, all of the other miniature guides in the series. It exemplifies why thinking is best understood and improved when we are able to analyze and assess it EXPLICITLY. The intellectual skills it emphasizes are the same skills needed to reason through the decisions and problems inherent in any and every dimension of human life.

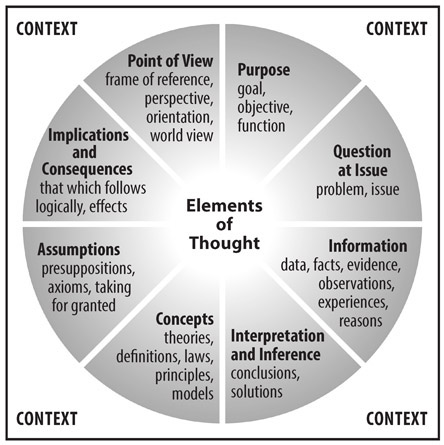

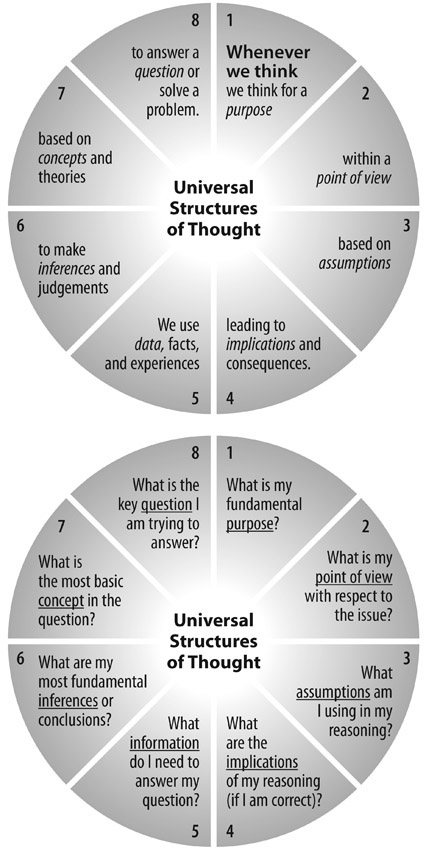

Everyone thinks; it is our nature to do so. But much of our thinking, left to itself, is biased, distorted, partial, uninformed, or downright prejudiced. Yet the quality of our life and of what we produce, make, or build depends precisely on the quality of our thought. Shoddy thinking is costly, both in money and in quality of life. If we want to think well, we must understand at least the rudiments of thought, the most basic structures out of which all thinking is made. We must learn how to take thinking apart.

Eight basic structures are present in all thinking: Whenever we think, we think for a purpose within a point of view based on assumptions leading to implications and consequences. We use concepts, ideas and theories to interpret data, facts, and experiences in order to answer questions, solve problems, and resolve issues.

Thinking, then:

generates purposes

raises questions

uses information

utilizes concepts

makes inferences

makes assumptions

generates implications

embodies a point of view

Each of these structures has implications for the others. If you change your purpose or agenda, you change your questions and problems. If you change your questions and problems, you are forced to seek new information and data. If you collect new information and data...

Essential Idea: There are eight structures that define thinking. Learning to analyze thinking requires practice in identifying these structures in use.

The words thinking and reasoning are used in everyday life as virtual synonyms. Reasoning, however, has a more formal flavor. This is because it highlights the inference-drawing capacity of the mind.

Reasoning occurs whenever the mind draws conclusions on the basis of reasons. We draw conclusions whenever we make sense of things. The result is that whenever we think, we reason. Usually we are not aware of the full scope of reasoning implicit in our minds.

We begin to reason from the moment we wake up in the morning. We reason when we figure out what to eat for breakfast, what to wear, whether to make certain purchases, whether to go with this or that friend to lunch. We reason as we interpret the oncoming flow of traffic, when we react to the decisions of other drivers, when we speed up or slow down. One can draw conclusions, then, about everyday events or, really, about anything at all: about poems, microbes, people, numbers, historical events, social settings, psychological states, character traits, the past, the present, the future.

By reasoning, then, we mean making sense of something by giving it some meaning in our mind. Virtually all thinking is part of our sense-making activities. We hear scratching at the door and think, Its the dog. We see dark clouds in the sky and think, It looks like rain. Some of this activity operates at a subconscious level. For example, all of the sights and sounds about us have meaning for us without our explicitly noticing that they do. Most of our reasoning is unspectacular. Our reasoning tends to become explicit only when someone challenges it and we have to defend it (Why do you say that Jack is obnoxious? I think he is quite funny). Throughout life, we form goals or purposes and then figure out how to pursue them. Reasoning is what enables us to come to these decisions using ideas and meanings.

On the surface, reasoning often looks simple, as if it had no component structures. Looked at more closely, however, it implies the ability to engage in a set of interrelated intellectual processes. This thinkers guide is largely focused on making these intellectual processes explicit. It will enable you to better understand what is going on beneath the surface of your thought.

Essential Idea: Reasoning occurs when we draw conclusions based on reasons. We can upgrade the quality of our reasoning when we understand the intellectual processes that underlie reasoning.

Be aware: When we understand the structures of thought, we ask important questions implied by these structures.

Reasonable people judge reasoning by intellectual standards. When you internalize these standards and explicitly use them in your thinking, your thinking becomes more clear, more accurate, more precise, more relevant, deeper, broader and more fair. You should note that we focus here on a selection of standards. Among others are credibility, sufficiency, reliability, and practicality. The questions that employ these standards are listed on the following page.