Contents

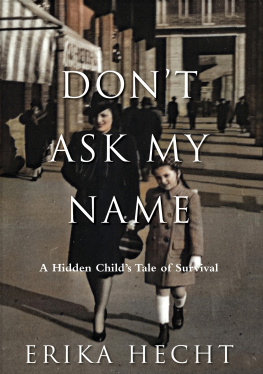

DONT

ASK MY

NAME

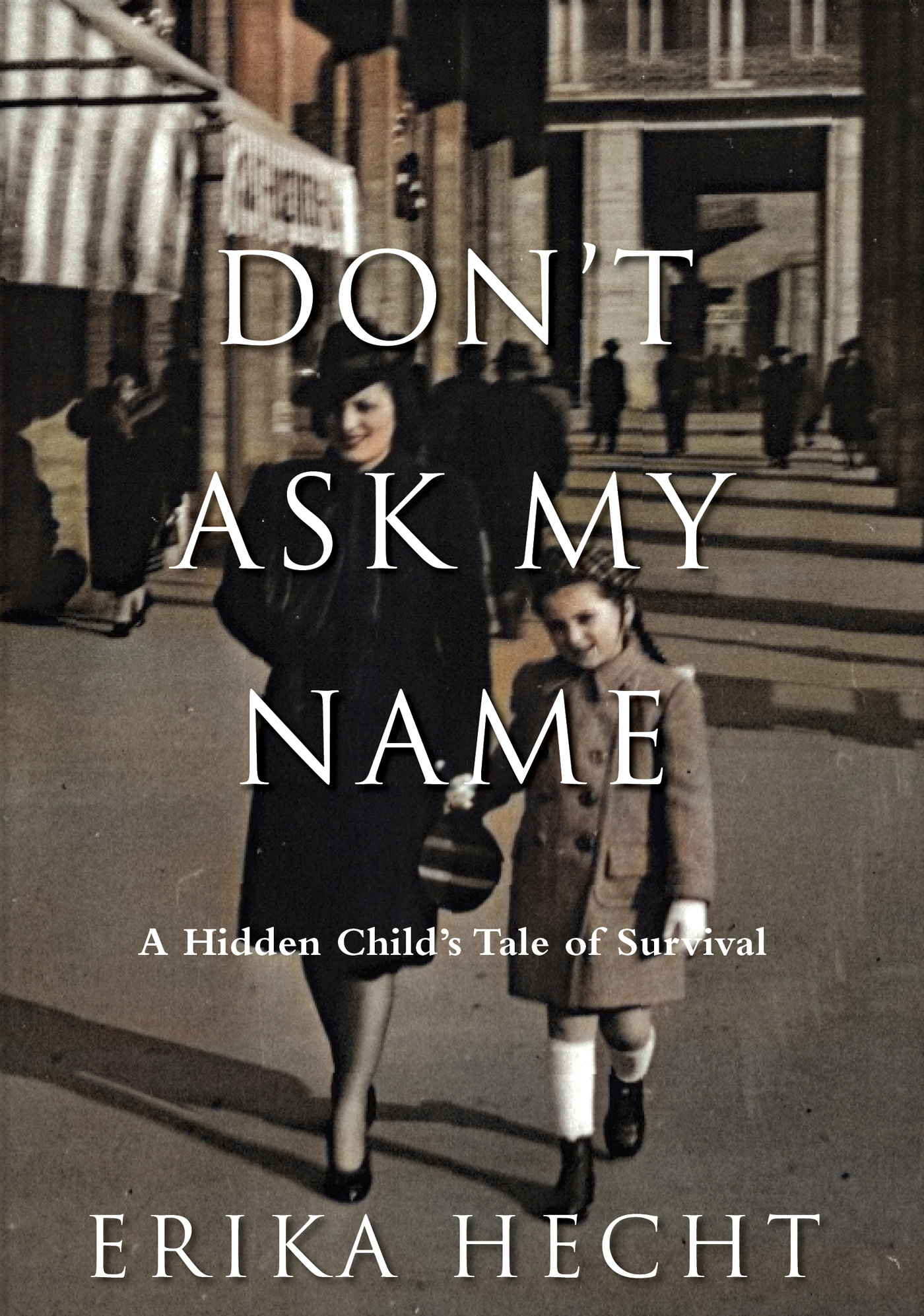

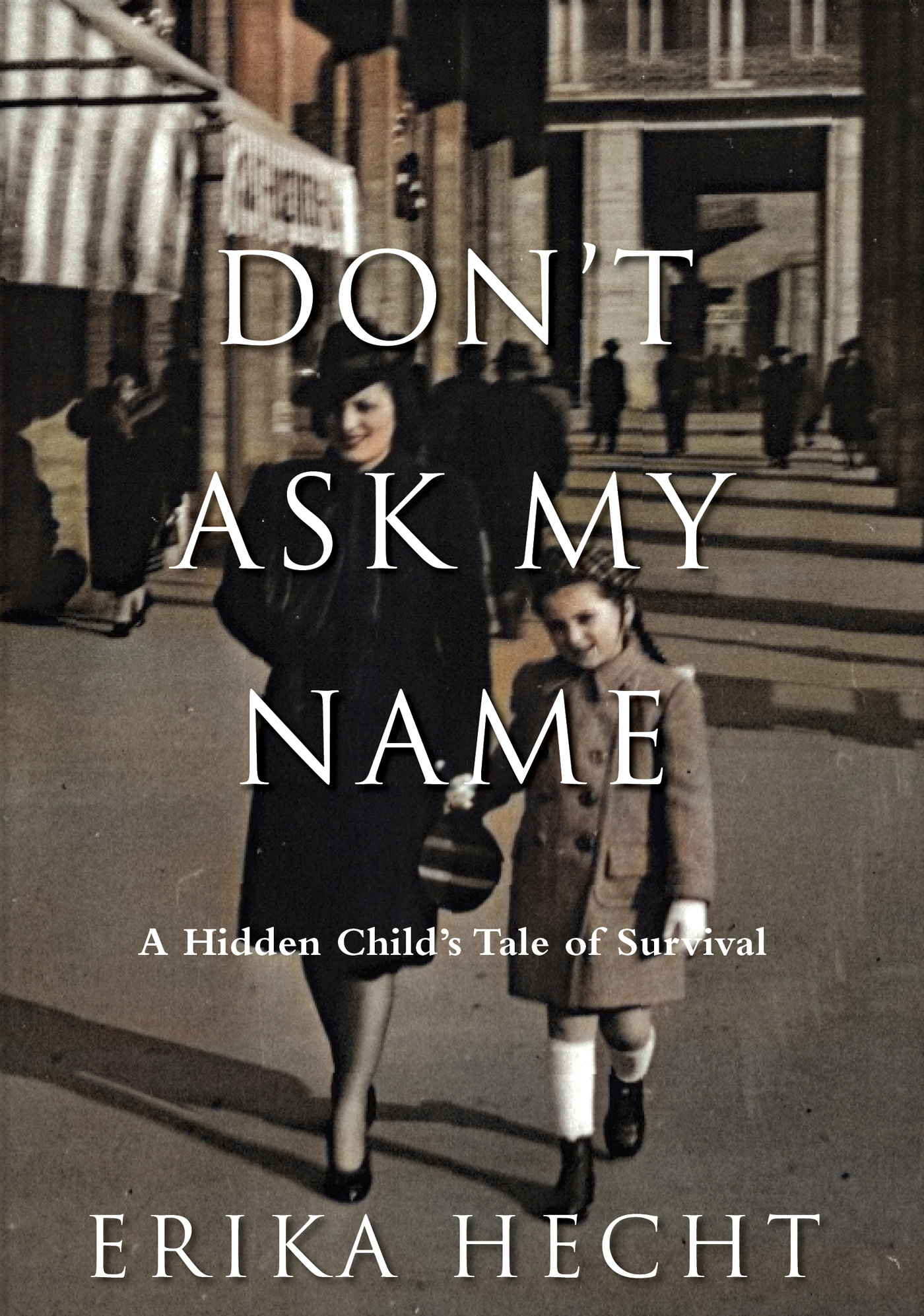

This book is to honor the memory of the children who did not survive the Holocaust and is dedicated to those who lived and had the courage to confront the trauma of their survival.

DONT ASK MY NAME

Copyright 2021 by Erika Hecht

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published by

EAST END PRESS

Bridgehampton, NY

Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-7345268-3-7

eBook ISBN: 978-1-7345268-4-4

first edition

Book and Jacket Design by Pauline Neuwirth, Neuwirth & Associates, Inc.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book could not have come into existence without the support, enthusiasm, and contribution of several committed people.

First and foremost, I want to acknowledge my daughter, Marion, who has been the most supportive and encouraging person since I first began to talk about my experiences. The more stories she heard, the more convinced she became about the necessity for me to write them all down. She accompanied me to Hungary on my roots trip in 1993, which helped me verify all of my memories and was further confirmation that this book had to be written. She remains to this day my most ardent supporter.

Another person without whose expertise and cooperation this book could not have happened is my friend Anne McCormack, a supportive and understanding soul, whose ability with the computer transformed my handwritten stories into a manuscript. It was a long, sometimes difficult process, but she never lost faith in my ability to finish the book. Her patience was endless. As the years went by, she was even able to read my handwriting.

Andrew Skonka has also been a continuing support in many aspects of my life and was always available to help with the technical aspects of putting the book together.

There were other helpful and positive influences over the years, the most notable being the Ashawagh Hall Writing Group, which I belonged to for many years. We met every week over the winters, reading from our manuscripts and receiving criticism and inspiration from our very accomplished peers.

Conversion

1937

Y ou have to behave , my mother says. You have to be very, very good. Her voice is serious, low, and threatening, and her grip on my hand is firm as she pulls me along with her. We are walking toward a big yellow building. This is the church, she says. Watch your step, she says, and, What are you staring at? when I stumble on the steps leading to the churchs entrance. Mother picks me up and impatiently carries me the rest of the way up the stairs. Somehow, I know and understand that she is afraid. I am three-and-a-half years old.

We go inside. It is dark and smells of burning wood, like our stove at home when the fire is about to go out. Many candles are burning near the walls, but it is still too dark to make out the pictures hanging above them. I am cold and frightened and I tell my mother that I want to leave. No, she says, no, no, no. I start to cry, but to no avail. She continues to pull me along with her toward the front. The Pater is waiting for us, she says. Now stop crying, dont ask any questions, and be a good little girl.

Where are the birds? I ask as we pass what looks like a birdbath on the way to the front. It looks exactly like the one in my cousin Marikas garden. Mother stops for a moment and then she says, That is holy water. Now you must really be quiet or else!

The Pater wears a long black dress. He stands on the stairs in front of a railing. I can see two boys standing behind him and wonder why they are wearing nightshirts. The Pater starts to speak to my mother slowly in a low voice. He is very serious. I cannot understand anything he is saying. Mother is listening, nodding, and talking to the Pater without paying any attention to me. I am getting bored. I say, I want to go home. Im hungry, but she continues to listen only to the priest. Suddenly, my mother kneels down on the step in front of him. Why is she doing that? Is there some dirt on the floor she wants to clean? Did she see a bug? No, she is still looking at the priest, listening. I am so frightened that I start to cry again. When the priest puts something in my mothers mouth, my crying turns into a wail, and I continue to wail even as we are leaving the church.

Outside the sun is shining. It is warm, so why is my mother shaking? Two ladies, her friends, are waiting for us. They are speaking to her, comforting her, telling her that everything will be all right. They tell me to be a good girl, to stop crying, but I cannot. Mother lifts me up, and I see that she too is crying. She continues to carry me as we walk away from the church, bouncing me up and down to comfort me, or maybe herself. She keeps repeating the same words louder and louder: We are Christians now. We are Catholics. We are safe. The bastards cannot hurt us. Nobody can hurt us. We are Christians.

Prologue

New York

1991

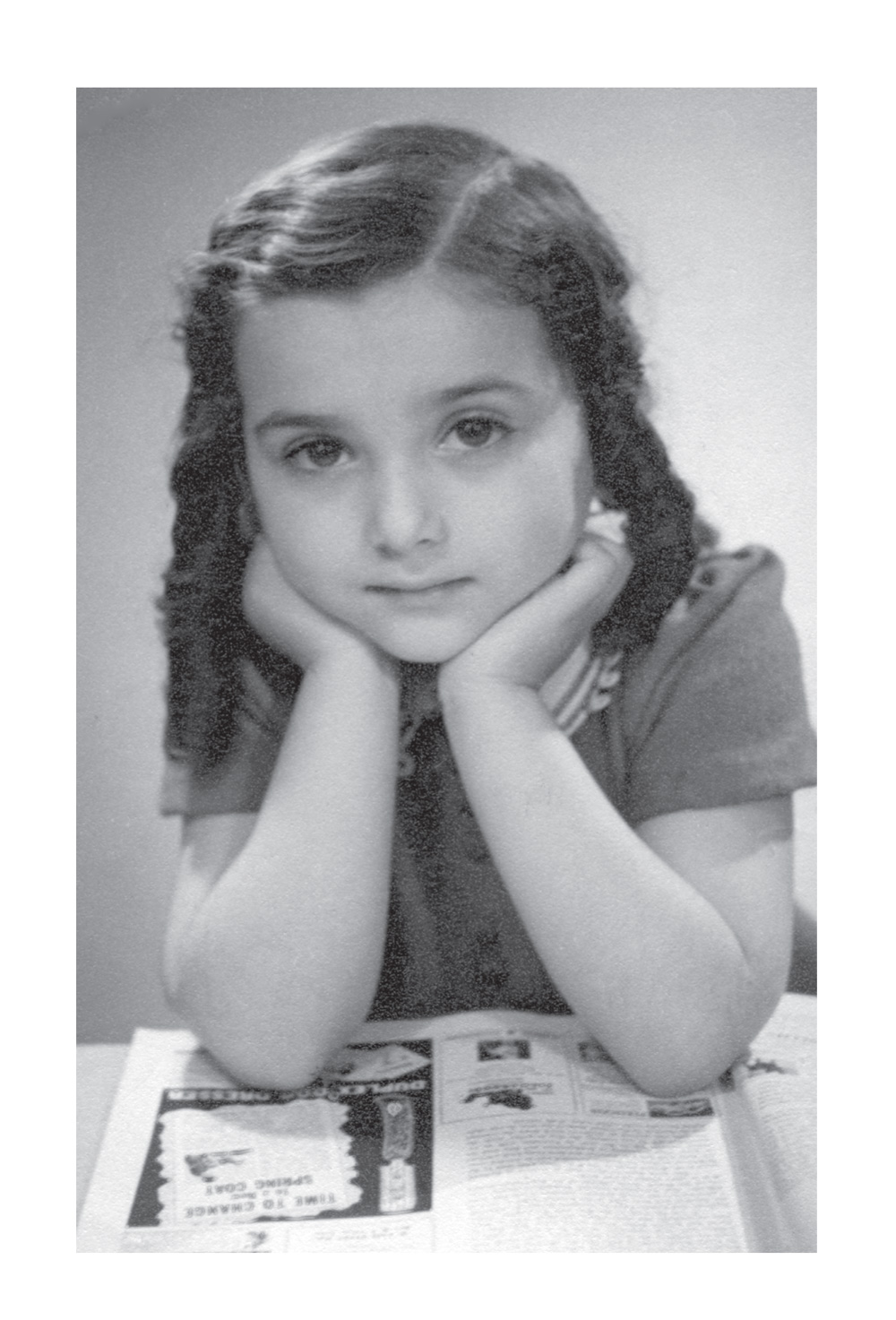

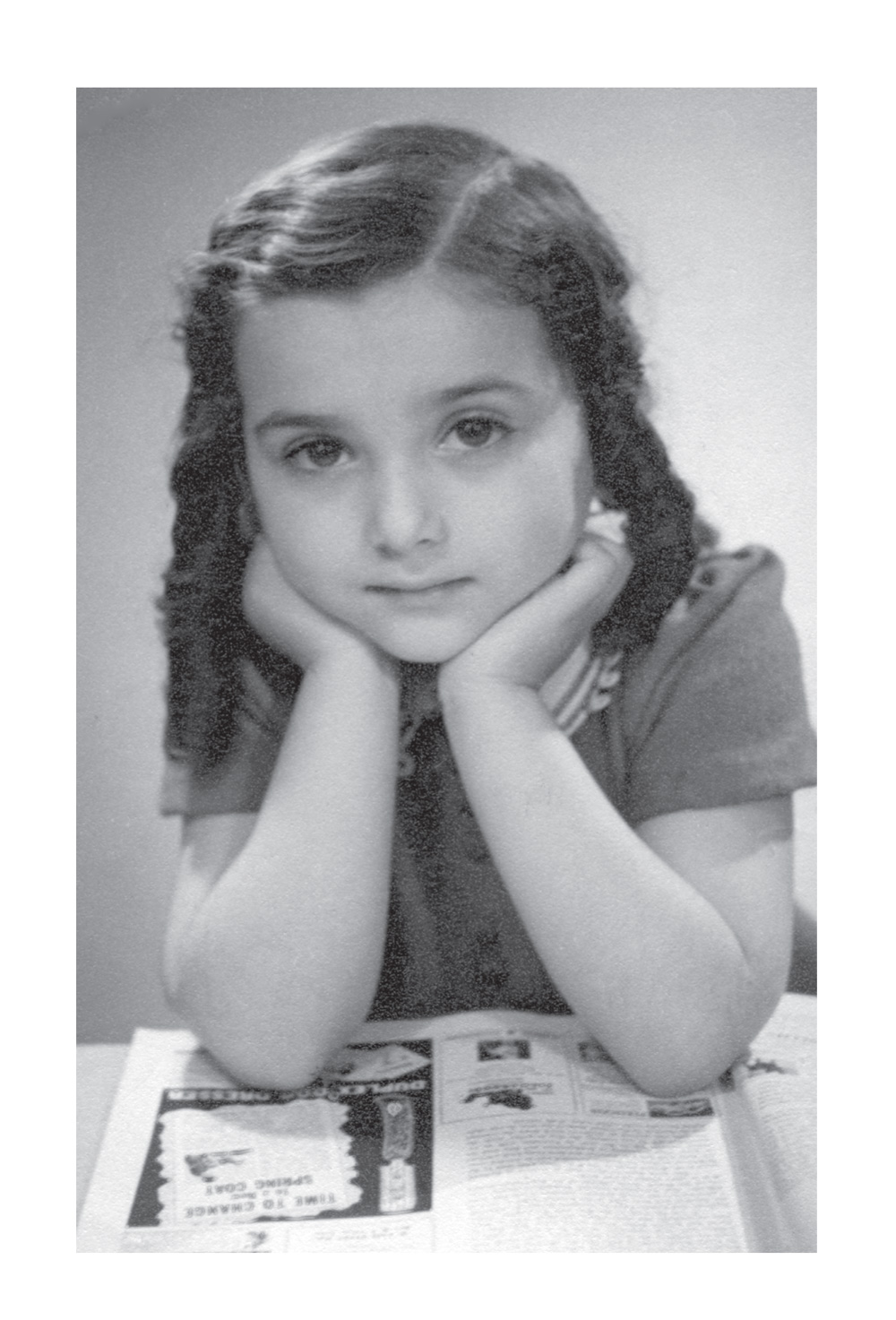

A s I leaf through New York magazine on a sunny Sunday afternoon in Montreal, the picture of a young girl disrupts my musings. She looks like me, or at least what I must have looked like in 1945 when the war ended. The hairdo, strict and orderly; the skirt, the hem just below the knee; and her serious expression staring into the camera brings to mind one particular photograph taken of me at that time. The picture in the magazine accompanies an article describing a forthcoming conference in New York, the very first conference for The Hidden Children of the Holocaust. The article gives a vivid explanation of the term Hidden Children. It refers to Jewish children who were provided false identities and survived World War II as Christians. The lies these children were obliged to tell and the secrets they had to keep accompanied them the rest of their lives, and according to the article, some fifty years later, the now-adult children are finally starting to talk. I have never before seen anything in print about Hidden Children. Reading the article moves me deeply. The girl in the picture was a Hidden Child, and until now, almost fifty years later, she has never talked about how the memories of her experiences have influenced her life. Nor have I.

My peaceful afternoon is shattered. Memories I didnt find necessary to remember are starting to invade my consciousness. Although I was converted to Catholicism with my mother in 1937, when I was three and a half, by 1942 the anti-Jewish laws in Hungary had changed. Our conversion no longer exempted us from being Jewish. By 1942, to be exempt from the anti-Jewish laws, it was required to document four non-Jewish grandparents. Although we were Catholics, my family had to find other ways of posing as non-Jews in order to survive Nazi persecution. We were fortunately able to acquire false identities through fake birth certificates and other pertinent documents and move to a village where we were not known, so that we could live as non-Jews. I was required from a very young age to lie and to keep secrets in order to survive.

Next page