Of all the persistent qualities in American history, the values

attached to property retain the most power.

Patricia Nelson Limerick, The Legacy of Conquest

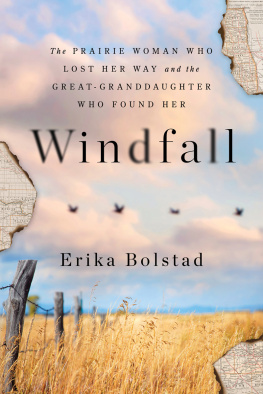

Copyright 2023 by Erika Bolstad

Cover and internal design 2023 by Sourcebooks

Cover design by theBookDesigners

Cover images Encyclopaedia Britannica/UIG/Bridgeman Images, John M. Chase/Getty Images, sbayram/Getty Images

Case images belterz/Getty Images, Flavio Coelho/Getty Images, Nattawut Lakjit/EyeEm/Getty Images

Internal design by Laura Boren/Sourcebooks

Internal images Erika Bolstad

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systemsexcept in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviewswithout permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks.

This book is a memoir. It reflects the authors present recollections of experiences over a period of time. Some names and characteristics have been changed, some events have been compressed, and some dialogue has been re-created.

Published by Sourcebooks

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 605674410

(630) 961-3900

sourcebooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bolstad, Erika, author.

Title: Windfall : the prairie woman who lost her way and the great-granddaughter who found her / Erika Bolstad.

Description: Naperville, Illinois : Sourcebooks, 2023. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: Author Erika Bolstad was shocked to learn she had inherited mineral rights in North Dakota in the throes of an oil bonanza. Determined to unearth the story behind her unexpected inheritance, she followed the trail to her great-grandmother, Anna, who her family had painted to be a courageous homesteader who paved her way in the unforgiving American West. But, Bolstad discovers a darker truth about Anna than her family had ever shared. With journalistic rigor, she unearths a history of environmental exploitation and genocide as well as the modern-day consequences of the Great Plains Dream: we could be rich-- Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022030626 | (hardcover) | (epub) | (adobe pdf)

Subjects: LCSH: Bolstad, Erika. | Petroleum industry--North Dakota. | Mineral rights--North Dakota. | Family secrets.

Classification: LCC HD9567.N9 B65 2023 | DDC 338.2/728209784--dc23/eng/20220715

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022030626

For Nan

CONTENTS

Part I

1

FRACTURED

December 2009

North Dakota crude: $63.96 per barrel

H ER NAME WAS A NNA J OSEPHINE S LETVOLD . T HAT S ABOUT ALL I KNEW when all of this began during the darkest days of the Great Recession.

Anna, my mother told me, was a plucky woman who, on her own, settled the untamed prairies of northwestern North Dakota. The family lore was made even more romantic for what it left out: Anna disappeared from her homestead in 1907, lost to time and the vast plains.

More than a century later, an oil company sent my mother a $2,400 check. The oil company was leasing mineral rights along the edges of the booming Bakken oil fields of North Dakota. From the oil company, my mother learned she was an heir to mineral rights below the surface of the land where Anna once had a homestead. The check arrived in a manila envelope a few days before Christmas in 2009, its auspicious timing further confirmation of a family theory, never articulated but well understood, that unexpected windfalls have a way of showing up when they are most welcome.

In 1951, when my mother was just six years old, her father had signed a lease with an oil company, during the first oil boom in North Dakota. It was on the windswept land where Anna, his mother, once staked her claim. The oil company never drilled on Annas land, but it kept renewing the lease for more than a decade. All that lease money was enough to send my mother to collegeshe was the first person in her family to go.

My mother loved a windfall; how could she not? Her entire life, shed heard the promises blowing across the Great Plains. She bought lottery tickets whenever the jackpots soared and scratch-offs on a whim. She stockpiled pocket change to play the slot machines at the Spirit Mountain Casino near the western Oregon town where she and my father raised us. Do you know how long you can make ten dollars last on penny and five cent slots? she once asked me. She took out loans, secure in the knowledge that there would, somehow, be money to pay them off when the time came. It had always been that way; it had always worked.

Someday, all this will be yours, my mother promised.

We knew she was dying. A few months before the envelope arrived in her mail, an off-duty nurse found our mother passed out in a gym locker room from yet another heart attack. My sister, Stephanie, lived in Miami, and I lived in Washington, DC. By the time we both got to the hospital in Oregon, our mother was alert enough to ask us to bring in her jewelry. She told us she had picked out what she wanted us to have.

In my mothers office was a handwritten ledger on lined notebook paper detailing the $72,000 in medical debt she and my father owed to the hospital, to a cardiologist, and to the ambulance company. The oil companys $2,400 check barely made a dent.

Three months after she learned of her inheritance in North Dakota, my mother died.

The night of her death, I sat on the floor of my cold apartment in Washington, DC, the phone pressed to my ear as my father shared the news. My mothers caregivers, experienced with such transitions, could tell from the way she was breathing that the end was near. They urged my father to stay instead of going home for the night. My father wept as he described my mothers last few breaths. It was the first time I had ever heard him cry.

My grief came wrapped in guilt. I should have been there at the end. I knew it was the loneliest my father had ever been. But I couldnt afford to fly back to Oregon yet again. I had been there twice since my mothers most recent heart attack.

Shortly after the excitement of President Barack Obamas inauguration, the executives at the media company where I worked laid off hundreds of my colleagues across the country, and they cut my pay by more than $350 per month. I tried not to think too much about the collision course of my reality: I worked for a floundering newspaper chain crippled by the recession, and I rented a too-expensive Washington, DC, apartment. Until that point, my life had seemed to be on a steadily upward trajectory. One job always led to another better paying, more prestigious one.

But in 2009, I was never sure whether my rent check would clear, until one day it didnt. I barely had money to get my hair cut anymore let alone afford the honey-colored highlights that made me a little brighter, a little blonder.

The night of my mothers death, I pressed my back into the vertical lines of the radiator, trying to offset the hollowed-out feeling in my belly with warmth and some sort of sharp, physical sensation. The nubs of the carpet pressed into my bottom. I could see all the dog hair under my bed. I put on a favorite black turtleneck and kept it on for several days. It was a warm, cashmere cocoon that insulated me from the assault of a cold March and the ache of loss, deep in my gut.

Next page