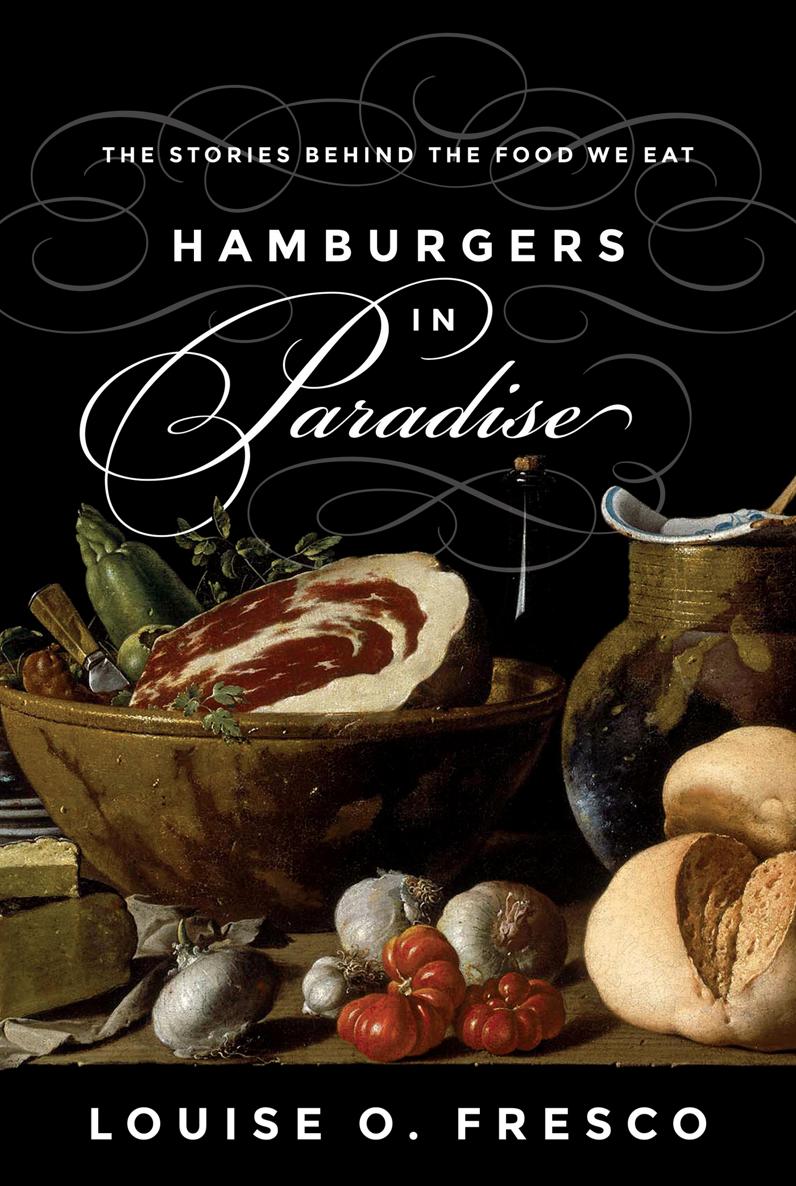

HAMBURGERS

IN

Paradise

THE STORIES BEHIND THE FOOD WE EAT

LOUISE O. FRESCO

Translated by Liz Waters

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton & Oxford

English translation copyright 2016 by Princeton University Press

This is a translation of Hamburgers in het paradijs, copyright 2012 Louise O. Fresco

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

THE HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION, NIV Copyright 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

Jacket art: Detail from Luis Melndez, Still Life with Bread, Ham, Cheese and Vegetables, about 1772. Photograph 2015 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fresco, Louise O., author.

[Hamburgers in het paradijs. English]

Hamburgers in paradise : the stories behind the food we eat / Louise O. Fresco ; translated by Liz Waters.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-16387-1 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Food supplySocial aspects. 2. Food supplyHistory. 3. Food consumption. 4. Food security. I. Waters, Liz, translator. II. Fresco, Louise O. Hamburgers in het paradijs. Translation of (work): III. Title.

HD9000.5.F73513 2015

338.19dc23

2015013030

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

N ederlands letterenfonds dutch foundation for literature | This book was published with the support of the Dutch Foundation for Literature. |

This book has been composed in Sabon Next LT Pro with Montserrat and Bickham Script display by Princeton Editorial Associates Inc., Scottsdale, Arizona.

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

Color plates follow pages .

INTRODUCTION

FoodA Voyage of Discovery

Food is a source of intense confusion these days. Can we justify continuing to eat steak when every cow emits greenhouse gases of the worst kind? How can we opt for cereals instead, if a bowl of muesli entails carbon emissions equivalent to a drive to the supermarket in the next village? Is it really sensible to eat more fruit if it has to be flown in from distant places, where it may have been picked in unhygienic conditions by underpaid workers, simply because the choice of seasonal fruit is inevitably limited in winter in northern latitudes? Is sugar ultimately to blame for all our health problems, and should we switch to honey? Or does honey contain the same molecules? Ought sugar to be banned altogether, or is it a cheap source of calories and a source of employment in poor countries? Anyhow, we can make biofuel from sugar, which is surely good for the environment. Or is it? Perhaps the government ought to regulate and tax the consumption of food as it does tobacco. Except that if fat is rationed or made relatively expensive, then just about everything that tastes good will have a stigma attached to it. In any case, that degree of state interference is incompatible with our love of freedom. We have a right to say what goes on in our own kitchens, at the very least, you might think. All right, so we need better information, and a ban on advertisements aimed at young children. And shouldnt we immediately stop subsidizing farmers, given that it causes poverty in the rest of the world? Or is that not how the world market works? Do we want to buy tomatoes from low-wage countries because that will help to create jobs, or from our own efficient greenhouses? Or from Spain or Italy for solidaritys sake, in light of the economic crisis in member states of the European Union? Should we cease producing meat altogether? Those horrifyingly vast milking parlors, those factory-farmed chickens. Or is large-scale food production a blessing for humanity? And what about the dangers of genetically modified food? Might it soon prove to be our salvation? A small risk is acceptable, isnt it? Are we being manipulated by big business and advertising, or have the food industry and the supermarkets made our food safer and healthier? Speaking of health, how can we live with the knowledge that there are now twice as many overweight people as undernourished people in the world?

This book looks at all these questions and more. Few subjects give rise to such contrasting visions, such uncertainty and fierce emotion. Everyone has an opinion about what we eat and how our food is produced and prepared. No one can remain indifferent to food, not a French housewife or an African politician, a farmer or a baker, a gourmet or a chef, and passions are easily roused by questions about which foods are good or bad. Food evokes profound feelings and old memories. Of course thats because food is essential; eating is something we do every day. We cant survive without it, as individuals or as a species, so its only logical that in all ages food has been subject to value judgments and taboos, and that rulers of the past, like governments today, have always wanted to keep control of food resources, waging war over them if necessary. None of this is new.

Dis-moi ce que tu manges, et je te dirai ce que tu es. (Tell me what you eat and Ill tell you what you arenot who you are, as the expression is sometimes wrongly translated.) Those oft-quoted words were first spoken in 1825 by a French chef named Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, and they have lost none of their relevance. But whereas he focused on a gastronomic code and the pleasures of eating, our concerns about food are now largely a matter of ethics and of knowledge about how the world works. Agriculture and food are bound up with culture and history, wherever and whoever we may be, and therefore with issues of equality and development. It makes no sense to look at our own food choices in isolation.

In the past decade or so, confusion over food has only increased. Who in the past ever asked where their broad beans came from, or what kind of milk they were drinking? Those who worried about hunger in the world were mainly concerned about starving children and drought-ravaged harvests. Today, everything that has to do with foodfrom seed grain and agriculture to food manufacture, supermarkets, and home cookeryis complex and riddled with ambiguities. Behind every peanut butter sandwich lies a long story of prices and feed stocks, climate and politics, big business and small farmers, tradition and scientific innovation, touching on everything from hidden ingredients to thoughtless consumption. Knowledge about that proverbial sandwich reaches the consumer in dribs and drabs, and knowledge only adds to our confusion. After all, what is good, whether for the environment, for our health, for those malnourished children, or for the animals? In this climate of confusion, modern social media provide a platform for everything and everyone: miracle diets and slimming pills, alternative fertilizers for the vegetable plot, traditional recipes for suet pudding, criticism of Europe for its E-numbers policy and its tight regulations, revelations about scientific conspiracies, moving stories by farmers wives, gruesome photographs of battery chickens alongside idyllic shots of cows in flowery meadows. Anyone who feels the urge can have their say.