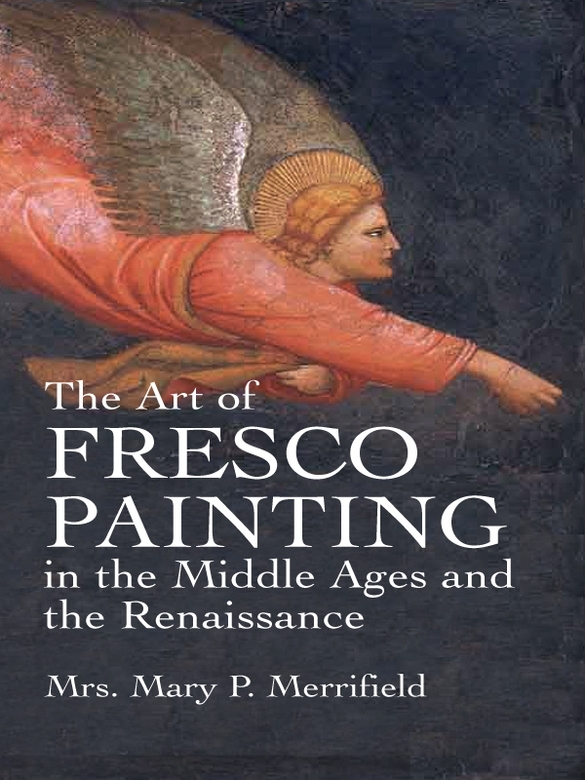

OF GUEVARA.

THE very interesting work from which the following commentary on part of the seventh book of Vitruvius is translated, was written in Spanish, by Don Felipe de Guevara, who has incorporated in his work all that is material and practical in Vitruvius, on the subject of fresco painting. Guevara occupied the post of Gentil - hombre de boca (that is the princes taster) to the Emperor Charles the Fifth.

The period of his birth is unknown; but he mentions, in the course of the work, that he fought in the celebrated victory at Tunis, and was in the island of Sicily in the year 1535. He travelled over Italy and Flanders, and appears to have been well versed in all that relates to the fine arts, which his situation in the court of Charles the Fifth and Philip the Second gave him ample opportunities of studying. Guevara appears to have been one of the greatest antiquaries of his time, and he possessed a valuable collection of medals and coins. He wrote a work, which has never been published, on the medals and coins of the different cities of Spain, which Ambrosio de Morales (who was personally acquainted with our author,) mentions in his Spanish antiquities in terms of the highest praise. The manuscript of this work on coins, to which Guevara alludes in his commentaries, (p. 244) is lost.

The present work, which is entitled Commentaries on Painting, must have been written after the year 1550, because the author mentions the work of Vasari which was published in that year, and before the commencement of the building of the Escurial, which was undertaken to commemorate the victory of St. Quintin in 1557. The work was dedicated to Philip the Second, but was never presented, nor was it ever published by the author, but was found in a booksellers shop by Don Josef Alfonso de Roa, a person eminent for his literary attainments and love for the fine arts, by whom it was sent to Don Antonio Ponz, author of the Viage de Espaa, and a friend of Mengs, who published it in 1788, and who wrote the notes appended to the following pages. to which his name is attached.

DIRECTIONS AND OBSERVATIONS FROM THE COMMENTARIES OF GUEVARA.

OF PREPARING WALLS AND ROOFS.It appears to me, (says Guevara,) that it will not be unseasonable, but on the contrary, necessary, since I have treated of the origin and beginning of painting in fresco, when old and dry is good, because this wood is solid and durable.

These cross pieces are to be nailed with strong nails, which will hold them firmly and prevent warping. But it must be observed, as we learn from Vitruvius, that these are not so durable and safe on flat roofs, as on those that are somewhat vaulted and curved, that in such walls this kind of work, which is called stucco, has great solidity ; and if the vault or ceiling of the apartment be made of bricks or other similar materials, many inconveniences would be avoided, and many things would be unnecessary that wooden roofs require, without covering the roof immediately with the first coating of mortar, as is usual in walls of stones and bricks.

Vitruvius next directs, that in roofs constructed of timber, the cross-pieces being first fixed and firmly nailed, reeds are to be bruised and split, and fastened to the roof (as the curve requires) with rushes or slips of Spanish broom tied firmly, as is now done when roofs are to be covered with gesso, and as was anciently the custom in Spain, and is still in Andalusia and the kingdom of Grenada, on account of the deficiency of wood in some places for this purpose.

The rushes or broom should be fastened to the reeds with great care and skill, for in this operation consists a great part of the perfection of the work, and they should be fastened with nails It appears to me that trusilar has the same meaning as our Spanish term xaharrar, which is the first coat of mortar given to the walls in order to prepare them to receive the whiter coats (blanqueada).

But although the signification of the word trusilar may be what I have said, and which I dare affirm, there arises a new doubt as to the nature of the mixture with which the roof has to be plastered; for it appears clear from Vitruvius, that the word trusilar does not describe either of the three sand coats, or either of the three marble coats, but is a distinct and separate process. Filandro, the interpreter of Vitruvius, suspects that trusilar means a coat of gesso, and Budeo affirms that this is the true signification of the word trusilar.

My opinion is, that trusilar always signifies the first preparation which we call exaharrar, and that it consists sometimes of gesso, and sometimes of other materials, as this does of which Vitruvius now treats; for he expressly directs, that on no consideration should gesso be mixed with this coat of plaster which the moderns call stucco, and he condemns such a mixture as bad and injurious or other similar substances are mixed, for it is well known that such a mixture works better and sets more firmly than one of chalk and sand.

My opinion is confirmed by the authority of Vitruvius himself, who in Book v. chap. x. speaking of roofs of vaults, says, inferior autem pars, qu ad pavimentum spectat, testa primum cum calce trussiletur , deinde opere tectorio sive albario poliatur. The meaning of these words is, that the front part of the roof that corresponds with the floor, should be first plastered with lime and the powder of baked pottery, such as bricks, tiles, &c., and afterwards the whitewash should be applied. This coat of lime and powdered brick having been applied, the roof should receive three other coats of lime and sand. After the application of these three coats, the wall should be smoothed or polished with pieces of smooth wood or other instrument used for burnishing, not liable to injure the surface. All these coats of plaster should be applied by rule and plummet, that no difficulties should afterwards arise when the wall has to be painted.

The plastering, says Vitruvius, which has been applied with care, will be firm and durable, and will never crack, because the burnishing will have given it great firmness and a polish of wonderful brilliancy, and the colours which are applied on it will be very bright and beautiful ; for colours which are employed and used upon roofs and walls that are fresh and just finished will last for ever, and will not fade, because the moisture which was in the lime when it was burnt in the kiln, is dried up and consumed in such a manner that it remains porous, and ready to receive and absorb anything added to it; and thus mixed and united with substances possessing other properties, and the materials and principles of the one being united with those of the others, when dry, the whole solidifies and hardens in such a manner after the mixture, that the lime seems to have recovered its peculiar properties and pristine hardness.

For this reason walls that are well finished, neither become soiled by age, nor, if rubbed or cleaned, do the colours come off or fade, unless they have been applied carelessly or in secco; so that if the coats of plaster have been applied in the manner described, they will be firm and bright, and have the property of resisting the ravages of time, for when only one covering of lime and sand, and another of lime and marble dust is applied, this weak crust cracks and spoils easily, nor does it, from its want of solidity, preserve the polish given to it by friction.

The same thing happens to plastering that is deficient in thickness as to a mirror which is too thin, and which therefore reflects but weak and uncertain images : on the contrary, the wall that has received a thick coat of plaster takes a durable polish, and presents to the spectators distinct and bright images; consequently, thin coats of plaster, which cover the surface but imperfectly, are not only liable to crack, but soon decay, whereas those that are prepared solidly with sand coats and marble coats of good thickness and which are afterwards well polished and burnished, not only cause the colours to appear lively and brilliant, but they present true images to the spectators.