PENGUIN BOOKS

Compose Yourself

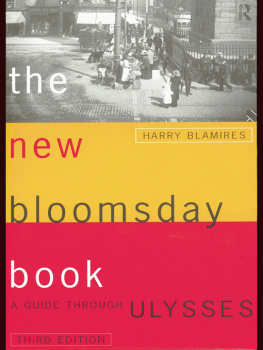

Harry Blamires, a graduate of University College, Oxford, was formerly Dean of Arts and Sciences at King Alfreds College, Winchester. He was Visiting Professor of English Literature at Wheaton College, Illinois, in 1987. The University of Southampton has awarded him a D.Litt. in recognition of his achievements as a writer. His total output of some thirty books includes fiction and theology, but he is widely known for his works of literary history and criticism. These include A Short History of English Literature (Routledge) and Twentieth-Century English Literature (Macmillan). For over three decades students in the USA and the UK have benefited from his classic guide to Joyces Ulysses, The New Bloomsday Book. He is also the author of The Penguin Guide to Plain English.

HARRY BLAMIRES

Compose Yourself

and Write Good English

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, Cnr Rosedale and Airborne Roads, Albany, Auckland, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

First published 2003

1

Copyright Harry Blamires, 2003

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject

to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent,

re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher s

prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in

which it is published and without a similar condition including this

condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-0-14-192264-5

Contents

Introduction

Learning to Write

This book is directed at readers who want to be able to express their thoughts on paper clearly and logically. We first learn to write in the same way as we first learn to speak, by practice and imitation. The human race has been peculiarly successful in handing on the ability to speak. Somehow we succeed in educating the young within the first few years of life to manipulate what is really one of humanitys most complex techniques. The development happens all around us from animal squeaks and dribbles to coherent speech in six years of intellectual immaturity. How is it done? Researchers have counted in thousands the number of words that the average child of three or four utters in a day. Clearly constant practice matters, but that practice is solidly based on imitation, not on formal instruction in How to Speak. We do not introduce our toddlers to grammatical rules or formulations, yet somehow they readily learn that John kicked Jane means something different from Jane kicked John.

The importance of the imitative factor in learning to speak is evident in the different accents, dialects, and indeed degrees of correctness that we hear around us. And since learning to write is equally a matter of practice and imitation, it is obvious that what we read will determine how well or badly we write. Good English usage is picked up by infection from what we hear and read. In the same way, however, bad usage is picked up by infection from what we hear and read. In that respect how healthy is the usage climate that we inhabit? Clearly we cannot expect to progress in expressing ourselves effectively on paper if the printed material we pick up day by day abounds in slovenly and inaccurate usage. Yet of recent years much has been revealed about the increasing faultiness in the English usage of such media as the daily press, magazines and the radio. I have myself made more than one attempt to display in print the kind of errors habitually made and to show how they could be best avoided.

Some of those who have paid attention to this problem have spoken as though it were chiefly due to a general ignorance of grammar. While it cannot be denied that grammatical error plays a part in damaging current usage, it has never seemed to me that the remedy for this situation was to be found simply in stuffing more and more grammatical formulations into the heads of either children or adults. One cannot investigate current usage for its defects without discovering that ignorance of grammar is not the gravest deficiency in it. Some of the faultiest sentences we read and hear nowadays are not in the least ungrammatical.

Getting a correct grammatical structure in a sentence is one thing. Using words meaningfully in a sentence is a different thing. The two matters are of course closely related. It would be difficult to think of a sentence which would be unambiguously sound and precise in the message it conveyed and yet which would be grammatically incorrect. But conversely it is easy to construct grammatically correct sentences which are deficient in meaning and offend common sense. There is nothing grammatically wrong with the following sentences: Three and four make five, Snails often suffer from schizophrenia, If you drink too much tea, you may explode.

Unless we recognize what an enormous amount of error in writing is due to careless thinking, we shall probably overestimate the damage caused by neglect of grammatical formulations. In my years in higher education I found that crude grammatical slips formed a small proportion of the total errors in written English. Indeed I sometimes found an unerring instinct for faultless grammar existing alongside a tendency to lose ones head over simple logical sequences. I remember once setting a test for mature students in which they were asked to improve or correct a series of faulty sentences derived from their own work. One of the sentences ran:

These intelligent and imaginative children are the result of our

educational reforms.

I was astonished to find that most of the improved or corrected versions ran: These intelligent and imaginative children are the results of our educational reforms. It seemed to me that instruction in formal grammar would not meet the crying need of these students. Grammatically, it seemed, they were keenly on the alert. Their need was simply to learn to think clearly; to ask themselves not Should the word result be singular or plural? but What is a result? and Can a child, however intelligent or imaginative, be defined as the result of an educational reform?

The Need for Sound Thinking

It is sound thinking that produces good English; it is unsound thinking that produces incorrect English. And by good English we mean wording that clearly and effectively conveys what we want it to convey. People tend to think that good English is just one of the options on offer for conveying what they have to convey. Indeed one comes across the assumption that good English imposes a rather troublesome demand to do something according to special rules which could be done just as well and much more easily without them. The reasoning is false. You might choose between various options if you had to make a journey to Manchester. You might go by train, by car or even by taxi. The point about these options is that they all deliver the same result. They all get you to Manchester. Faulty English is unlikely to convey exactly the same message as correct English. I have just heard a voice on the radio declaring that applicants for a certain requirement must say where they live and where their postcode is. Might not an applicant respond to this demand by saying: My postcode is in my diary along with my PIN number? The question Where is Johns address? is not the same question as What is Johns address? The same applies to the word postcode. Clearly the speaker should have said where they live and what their postcode is.

Next page