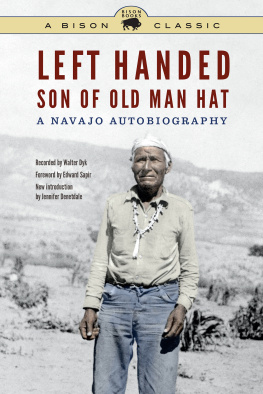

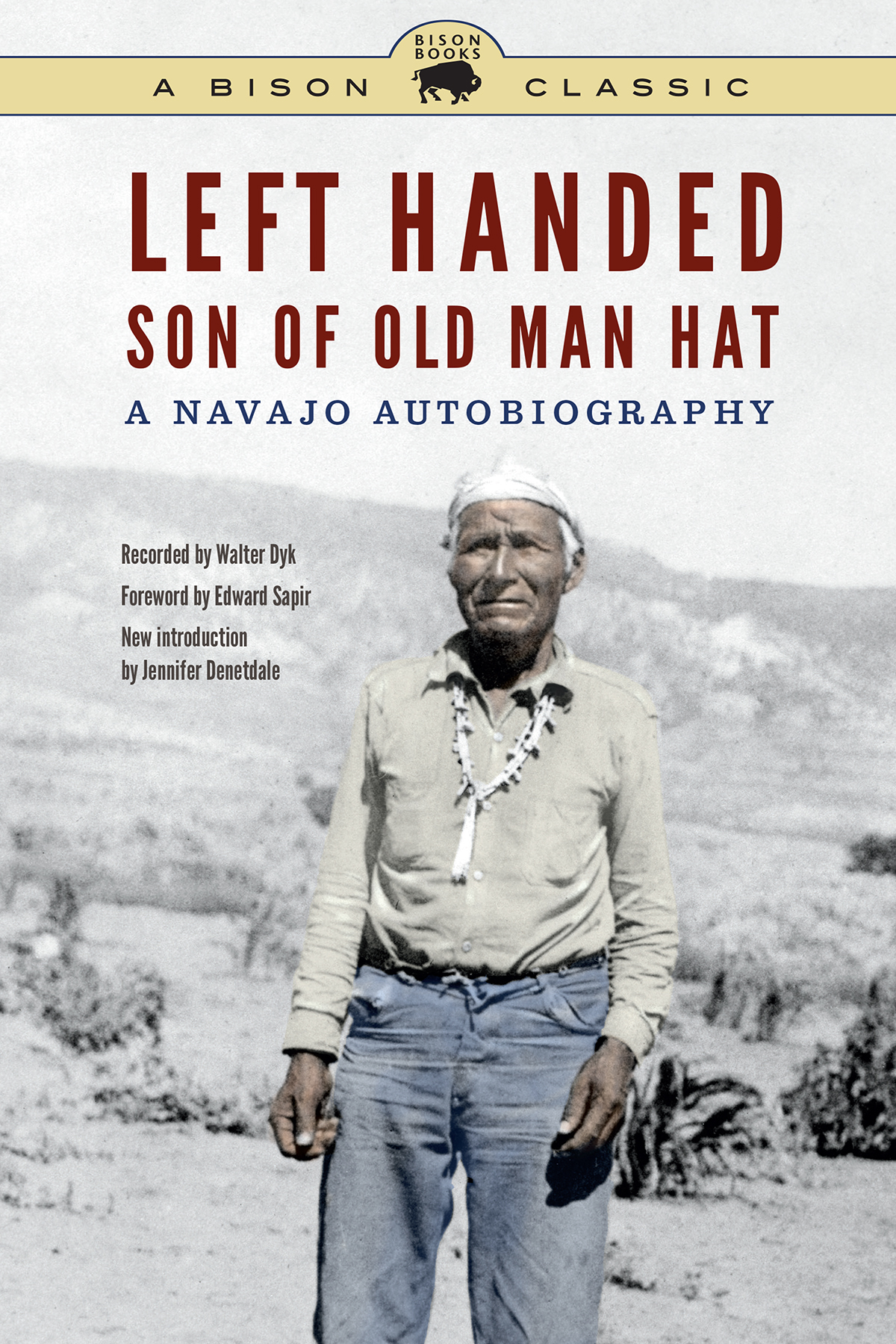

An extraordinarily vivid and detailed story, full of earthily realistic dialogue, told with an amazing storytellers craft.

An entertaining and absorbing story about Indian life.

Left Handed, Son of Old Man Hat

A Navajo Autobiography

Bison Classic Edition

Left Handed

Recorded by Walter Dyk

Foreword by Edward Sapir

New introduction by Jennifer Denetdale

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln and London

1938 by Walter Dyk. renewed 1966 by Walter Dyk.

Introduction to the Bison Classic Edition 2018 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

Previous Bison Books printings: 1967, 1995

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press.

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Left Handed, 1868 author. | Dyk, Walter, interviewer. | Sapir, Edward, 18841939, writer of foreword. | Denetdale, Jennifer, writer of introduction.

Title: Left Handed, son of Old Man Hat: a Navajo autobiography / recorded by Walter Dyk; foreword by Edward Sapir; introduction to the Bison Classic edition by Jennifer Denetdale.

Other titles: Son of Old Man Hat

Description: Bison Classic edition. | Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2018. | Originally published: Son of Old Man Hat. New York: Harcourt Brace, c1938. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017054281

ISBN 9781496205155 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN 9781496206213 (epub)

ISBN 9781496206220 (mobi)

ISBN 9781496206237 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH : Left Handed, 1868 | Navajo IndiansBiography. | Navajo IndiansSocial life and customs. | LCGFT : Autobiographies.

Classification: LCC E 99. N 3 L 545 2018 | DDC 979.1004/97260092 [B]dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017054281

Originally published in 1938 as Son of Old Man Hat: A Navaho Autobiography by Harcourt, Brace & World.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Contents

Jennifer Denetdale

In the twenty-first century the Din remain one of over two hundred Indigenous nations who struggle simultaneously with the mantle of their domestic dependent relationship with the United States and efforts to revitalize their distinctive teachings and values as guides to transforming their own governance and social and cultural institutions. The Navajo nations declaration to return to its traditional principles must also be tempered with the realities of at least three centuries of colonial invasions into Navajo country that have resulted in vast shifts politically, socially, economically, and culturally. Indeed, the last one hundred and seventy years of Navajos under American occupation created the conditions by which we are able to read in print the life story of a Din man who was born at the Bosque Redondo prison camp, where the American military held Navajos from 1863 to 1868, and then returned to the Navajo homeland with his family. Left Handed, Son of Old Man Hat is most often read as the narrative of a Din man who lived a traditional life based upon teachings and principles that predate the American war on Navajos, their incarceration, and the return to their homeland in 1868. However, as scholars of poststructuralism and postcolonialism point out, anthropology as a discipline was, and to a great extent, remains premised on the ideology that we can understand and appreciate Native peoples primarily through the categories of culture and tradition, but that these ways of life are still fast disappearing, just as they were in the early twentieth century. Walter Dyk arrived in Navajo country during a time of great upheaval when Indian Commissioner John Collier coerced Navajo leaders to endorse his livestock reduction policies, which Navajos saw as catastrophic; yet, Dyk makes no records of what Navajos faced or how they responded to changes they charged were as traumatic as the Long Walk. How then do we read Son of Old Man Hat when we consider that anthropologys motivations for inspecting exotic cultures and traditions are often critiqued today as integral to the United States colonial enterprise? Or that Navajos often enjoy reading this text and consider it to be a reflection of an era when livestock raising was central to a Navajo way of life? Or that Navajos may be strongly critical of the sexual theme present in this ethnography?

In 1934 Walter Dyk, supported by Yale Universitys fellowship from the National Research Council, arrived on the Navajo reservation to conduct fieldwork among Navajos. A student of Edward Sapir, Dyk had received other fellowships from the Harvard Psychological Clinic and was influenced by Sapirs research on the role of the individual in culture, including psychological studies on the individual and personality. In comparison to anthropologists of his time, including Clyde Kluckhohn and Gladys Reichard, Dyks publications are few and include this volume as well as A Navaho Autobiography (1947) and a volume published posthumously by his wife, Left Handed: A Navajo Autobiography. His publications include a few articles, including Notes and Illustrations of Navaho Sex Behavior (1951) on Navajo sexual mores, which reflects a predominant theme in this ethnography and has been remarked upon by several book reviews across several decades.

Dyks fieldwork among the Navajos is but one study among many others by anthropologists that shaped anthropology as a social science. During the early twentieth century, the discipline responded to Colliers call for cultural relativity and marked the relationship between research in the academy and its use to shape federal Indian policy. Dyks work is emblematic of the fields turn to cultural relativity and a focus on the categories of culture, tradition, and authenticity, all of which remain central to Native and Navajo studies. In the 1970s Standing Rock Sioux scholar Vine Deloria Jr. issued a scathing critique of anthropology as an enterprise that supported the ongoing colonization of Native lands and peoples, and his criticism was met with self-reflexivity on the part of the field. These modes of shifting meaning for anthropology must also be part of the engagement with this text. Layers of meaning provide multiple perspectives on Son of Old Man Hat, for on the one hand many Navajos review it favorably and declare that it offers a portrayal of traditional Navajo life based upon livestock raising, while on the other students of anthropology may use it to discuss shifts in the field, including the contributions of postcolonialism and settler colonialism as lenses through which to view anthropologys relations to Indigenous peoples. Given that Son of Old Man Hat is considered a classic of Navajo ethnography and taught in the classroom, it is potentially useful in many ways: for generating thoughtful discussions of currents in Navajo studies that take into account multifarious meanings, for weighing once again anthropologys claims of authority to represent Indigenous peoples, and for reflecting upon the present moment of anthropology, in which the discipline continues to make claims about its relationship to Indigenous peoples and is perhaps shifting as Indigenous peoples become the anthropologists and draw upon these ethnographies for their own purposes.