First published 2011 by Left Coast Press, Inc.

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2011 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Control Number 2005928676

Design and production services: Leyba Associates, Santa Fe, NM

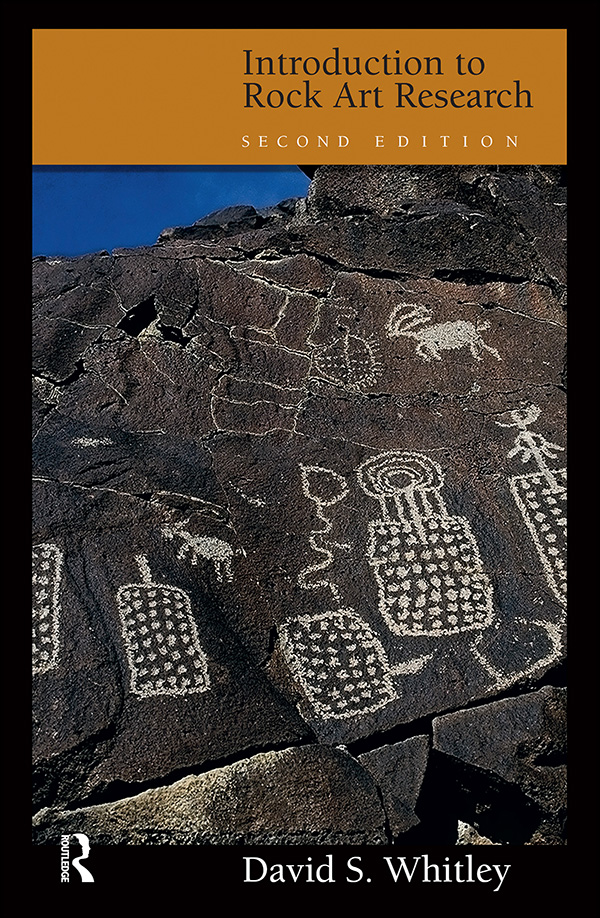

Cover design: Jane Burton

ISBN 978-1-59874-611-2 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-59874-610-5 (hardcover)

My original hope in writing the first edition of this book was that it would advance the emergence of rock art research as standard archaeological practice: a methods textbook is essential for any disciplinary subfield, and, perhaps surprisingly, none existed for rock art studies in 2005. It has been gratifying to see the original volume serve that purpose and, even more, be well received, perhaps the best example of which was its receipt of a Choice Outstanding Academic Award for 2006 from the American Library Association.

But things change, including the status and emphasis of rock art research, and, half a decade on, it was clear that a revised second edition was in order. Although there are a variety of minor additions in this version, including especially an expanded discussion of rock art site management plans and procedures, two particularly important developments warranted coverage. The first of these involves the latest advances in chronometric datingspecifically, the Holocene calibration of varnish microlamination dating by Tanzhuo Liu (Liu and Broecker 2007, 2008a, 2008b), which has the potential to greatly enhance petroglyph dating and is already being applied internationally (e.g., Dietzel 2008; Whitley and Dorn 2010; Zerboni 2008). This technique should revitalize a research area that had been hampered by controversy and confusion but is fundamental to the advancement of rock art research.

The first edition foreshadowed arguably the most important disciplinary tendency of the last half-decade: the increasing importance of site management in archaeological practicea circumstance that reflects the fact that the large majority of archaeologists are now employed in some form of cultural resources (or heritage) management, rather than in research or academia. Perhaps most basic to rock art site management is the need for condition assessments of sites: careful and knowledgeable evaluations of their physical integrity and the natural processes of degradation that may be affecting them. Rock art sites worldwide have suffered from the fact that there are few professionally trained conservators who can conduct condition assessments, the studies are time-consuming and expensive, and, frankly, rock art management is poorly funded. As a result, we tend to use our limited resources to (in essence) fight forest firesthat is, to conduct condition assessments on sites that have recognizable but already critical problems, and then try to fix the ongoing damage. Until recently, heritage managers had few other options, but, as everyone will acknowledge, this is an inefficient way to use our limited funding and a poor approach to managing our sites. What we needed was a method that was standardized, inexpensive, and quick, allowing us to identify condition problems before they became critical and making true advance planning in site management possible.

Recognizing this problem, and also understanding (as geomorphologists whose research specialty is rock weathering processes) that condition assessments could be standardized based on a series of empirical variables, Ron Dorn, Niccole Cerveny, and Case Allen have developed a rapid, replicable, and quantitative approach to this problem (Cerveny et al. 2006, 2007; Dorn et al. 2008). Known as the Rock Art Stability Index (RASI), this allows an archaeologist with minimal training to evaluate the status of a rock art panel, site, or series of sites in terms of relative degrees of endangerment (or, ideally, stability). Not only does this allow a resource manager to identify potential preservation problems before they become critical, and thereby efficiently allocate available funding for conservation, but it also establishes a basis for future site monitoring, another vital component of any site management plan.

In the first edition, I expressed the hope that, if there was a subsequent version of this book, it would include a detailed discussion of the rock art ethnography of farmers. My wish was that, whereas hunter-gatherer rock art ethnography has been generally well covered, much more research would occur on this understudied but important topic and that it could be covered in detail in the book. Although there have been a handful of significant contributions in this regard (e.g., Hays-Gilpin 2008; Zubieta 2006, 2009), the topic is still poorly understood, especially from a global perspective. Perhaps, if there is a third edition, this subject will finally receive the description and discussion that it deserves.

I would like to thank Mitch Allen for publishing the first edition as his first book for then-nascent Left Coast Press, and making this revision the presss first second edition; and my old friend Carol Leyba, for shepherding the manuscript into print. And thanks to Carmen Whitley for her dedicated work on the index

Tehachapi, California

September 2010

I was twelve years old when I decided that I would spend my professional career studying rock art. (I had already determined, as a three-year-old, that I would be an archaeologist when I grew up, causing me to wonder, ever since, whether it was a wise age to make a major career choice.) What tilted me toward rock art was a somewhat serendipitous visit on my first European trip to the cave of Niaux, France, with its remarkable corpus of Paleolithic art. (I knew about the caves near Les Eyzies and had planned to visit them with my parents on this trip, but we unexpectedly encountered Niaux in the Ariege first, before we got to the better-known Dordogne.) I remember being transfixed by the Pleistocene images on the walls of this impressive cave, and I recall spending much of the next year reading everything I could find about Paleolithic artwhich (as these things tend to go) wasnt much. Little did I know, at that time, that rock art research was a marginal topic in Anglophone archaeological research, or that I would eventually become a colleague and friend of the primary researcher at Niaux, Jean Clottes (e.g., Clottes 1995), our leading authority on Paleolithic art (e.g., see also Clottes 1997a, 1998, 2003; Clottes et al. 2005). Sometimes youth and innocence can be blessings, if not portents.