Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Bruce R. Smith 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

The thought that cut might be a phenomenon worth investigating first occurred to me in 2012 while writing a chapter on Making the Scene for The Cambridge Guide to the Worlds of Shakespeare. Cuts and cutting, I realized, were involved in all the varieties of scene that I was investigating: marked units in printed texts, engraved illustrations, extracts in anthologies of beauties of Shakespeare, outrageous behavior onstage and off. I am grateful to the Bogliasco Foundation for a two-month fellowship at the Ligurian Study Center that not only facilitated the writing of the chapter but put me into conversation with fellow residents whose work involves cutwork, including Yotam Haber, a composer who incorporates archived sounds and visual images in his work; Mary Ellen Strom, a video producer; and Stacy Woolf, an historian of American musical theater. I extend thanks to all of my fellow fellows at Bogliasco, but to these three in particular. My move from a chapter on scene-making to a projected book on cutwork was encouraged at just the right moment by Katherine Rowe.

For the invitation to deliver the 2014 Oxford Wells Shakespeare Lectures, for endorsement of my proposed topic, and for hospitality during my time at Oxford, I want to thank the Faculty of English, particularly Laurie Maguire, Emma Smith, Tiffany Stern, Bart Van Es, and Seamus Perry, Chair of the Faculty Board at the time of my visit.

Broader thanks are due to the students and colleagues who answered my questions and calls for advice at various times and pointed me toward instances of cutwork that I would otherwise have missed: Emily Anderson, Gina Bloom, Anston Bosman, Susan Bennett, David Carnegie, Sharon Carnicke, Christie Carson, Thomas Cartelli, Karin Chien, Christy Desmet, Michael Dobson, Richard Edinger, Gray Fisher, Brett Hirsch, Peter Holland, Farah Karim-Cooper, Jeffrey Knight, Kevin Laam, Douglas Lanier, Jeffrey Masten, Jean-Christophe Mayer, Jennifer Richards, Jessica Rosenberg, Amanda Ruud, Rebecca Schneider, Stuart Sillars, Steven Urkowitz, Paul Werstine, and Richard Wistreich. Many people offered passing suggestions along the way. If I have overlooked any of them, I do apologize.

Regarding Shakespeare-inspired videogames, I take to heart Espen Aarseths admonition that no one should analyze them without playing them: If we comment on games or use games in our cultural and aesthetic analysis, Aarseth insists, we should play those games (Aarseth : 190). I have not, I confess, been able to take Aarseths advice in every case, but I have instead framed my comments by drawing on the expertise of some of my students at the University of Southern California, several of whom are Game Design minors in the School of Cinematic Arts. I want to thank in particular Esteban Farjado, Jordan Klein, Patrick Tam, Kelsi Yu, and Yingbao Zhu. Another student, Jade Matias-Bell, introduced me to James P. Carses very useful distinction between finite and infinite games. For directing me to particular YouTube videos I am grateful to two other students: Omar Zineldine at USC and Carla Jenness in Middlebury Colleges Bread Loaf School of English graduate program.

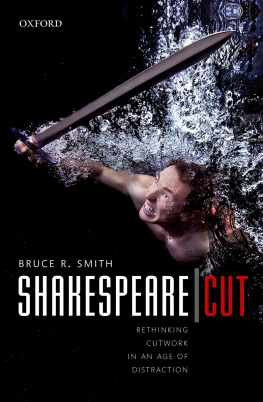

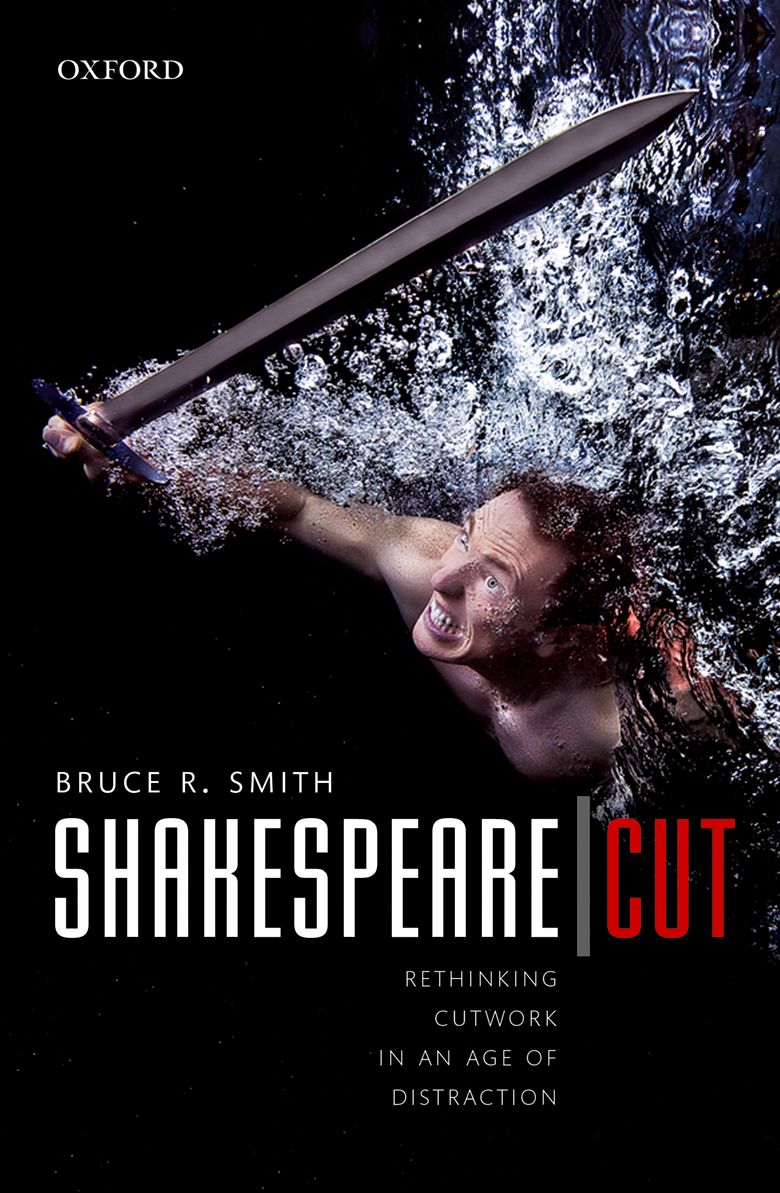

At Oxford University Press I have met with unfailing encouragement, sound advice, and sustaining patience from Jacqueline Norton, Senior Commissioning Editor for Literature, and Eleanor Collins, Senior Assistant Commissioning Editor for Literature. I thank both of them for their consummate professionalism. For editorial assistance I am grateful to my husband Gordon Davis. Helen B. Coopers copy-editing was meticulous and tactful. Subvention funds for illustrations were generously made available by Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences at the University of Southern California, through the good graces of Peter Mancall, Vice Dean for the Humanities and Social Sciences. In connection with illustrations and quotations, I want to extend special thanks to Isaac Gewirtz, Curator of the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection in the New York Public Library, for giving me access to the unpublished papers of William S. Burroughs; to Percy Stubbs of the Wylie Agency for granting permission to publish excerpts from the papers; and to the Tim Tadder Studio, Encinitas, California, for use of the photograph Once more unto the breach from the suite Diving into Character.

B.R.S.

Los Angeles, February 2016

Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations from Shakespeares plays and poems are taken from The Complete Works, 2nd edition, ed. Stanley Wells and Gary Taylor (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2005).

In quotations from early modern sources, spelling has been modernized but original punctuation has in general been retained.

Oxford University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet Web sites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such Web sites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Once more unto the breach.

Dear friends, once more.

King Henry to his troops, Henry V 3.1.1, in Mr William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies (1623), sig. h5

Tim Tadders image of Matthew Bellows as Henry V comes from a suite of photographs in which Tadder, an artist working in southern California, asked actors in the MFA acting program at the University of San Diego to reprise certain moments from Shakespearean roles they had playedbut this time in a different medium. (See .) Immersion: Diving into Character removed the actors from their usual mediumairand plunged them into water. Actually, most of the images in the series show the actors at the verge between the two media, just where water meets air. In that space between media, words that were once invisible in air have assumed visible, palpable presence as bubbles in water. In that intermedial space words that have assumed visible, palpable presence as bubbles in water are becoming, once again,