Page List

Cultivars of Polystichum setiferum and Dryopteris filix-mas enjoying light shade at John Masseys Ashwood garden. Light shade is achieved by removing lower branches of the trees.

First published in 2021 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2021

Martin Rickard 2021

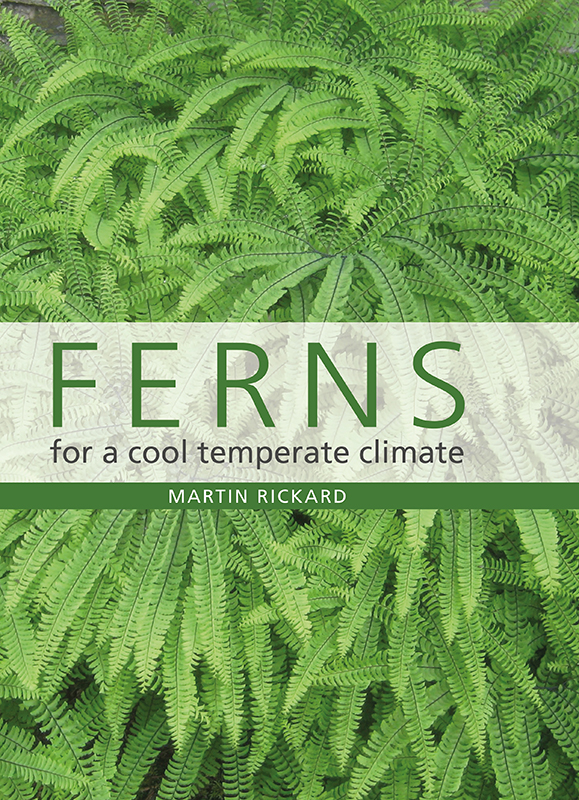

Cover images

Front cover: Adiantum aleuticum at Heddon Hall, Devonshire.

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 891 7

Cover design: Kelly-Anne Levey

Dedication

For my grandchildren, James, Gareth, Rebecca, Thomas, but particularly William, who knows many of these ferns already.

PREFACE

It is twenty-one years since I last ventured into the world of writing a brand-new account of ferns and fern gardening, and things have evolved since then! The ferns being grown in our gardens are changing annually as new treasures are introduced or sometimes old treasures are re-introduced with a new name. Fortunately, the genuinely new introductions are in the majority. More hardy ferns are gradually emerging from China, Japan and Taiwan; there are many more still to come, of that I am sure. I went with a group from the British Pteridological Society to Jizu Shan Mountain in Yunnan, China. We dragged ourselves up hundreds of steps to a height of over 3,000m. At that height climbing was difficult for unfit lowlanders but the ferns at the side of the path were astonishing: species and genera unknown to me. Collecting anything on our trip was strictly forbidden, but one day surely someone will bring these wonders into cultivation in the west, and our gardens will be much the richer. Surely species at this altitude must be hardy if grown in lowland cold sites in Europe. Some of the new introductions have come in from China, but more from Japan and Taiwan. There are other promising areas of exploration, too, such as the Himalayas, the South African Drakensberg Mountains, the high-altitude Andes and lower altitude mountains inland from So Paulo, Brazil.

Very often the species one sees in the mountains of the world are abundant locally. Collecting some spore would hurt no one but the Nagoya agreement has put an end to that. (The Nagoya Protocol of 2010 gives the nation where the plant grows ownership of its genetic material. Plants cannot be collected and cannot be raised from wild collected seed. Plants in cultivation before 2010 can be propagated freely.) I have not yet been aware of a single fern being introduced within the Nagoya rules, but it is to be hoped that perhaps some large nurseries are making progress.

INTRODUCTION

In giving a short history of ferns and fern growing I have mentioned a number of books, as they offer a useful insight into what was cultivated at particular times. The Victorian love of all things ferny in the house and in the garden is a testament to the ferns popularity. The appearance of Victorian nurseries is another clear indication, although many may not have been very profitable.

is devoted to ideas about using ferns in the garden, illustrating them with pictures from gardens, usually public but sometimes private. I hope I have checked with everyone that it is OK to use pictures of this and that. If there is anyone who has slipped through my checks I hope they will accept my apologies.

In the AZ of ferns () I have decided to leave out some species mentioned in previous books. I have continued to cover the principal tree ferns but have left out those obviously not hardy enough to grow even in the warm and wet western extremities of Europe. I have omitted quite a few Dryopteris species, simply because they are often rather like each other and I find that most gardeners are not keen to get them all. The best species are included, like Dryopteris wallichiana, as are most cultivars. I have included many rare species and cultivars possibly rather optimistically but I notice that many former rarities are becoming less rare, and I hope this trend will continue.

What are Ferns?

Ferns are a group of plants linked by their DNA. Recent research has shown that fern allies (club mosses, quillworts and selaginellas) are not ferns. They are not even closely related to ferns, but horsetails are ferns. In this book I have therefore given no coverage of quillworts (Isoetes) or Selaginella and only a passing mention of clubmosses (Lycopodium). Fortunately, all the plants that look like ferns, apart from Asparagus, which is a lily, are ferns. Some plants which do not look like ferns are ferns, such as Ophioglossum vulgatum. It is quite common but rarely noticed, hidden by other vegetation in grassland, usually calcareous. A curiosity if cultivated.

Ophioglossum vulgatum at the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh. The erect fronds are 2530cm tall and carry the spores.

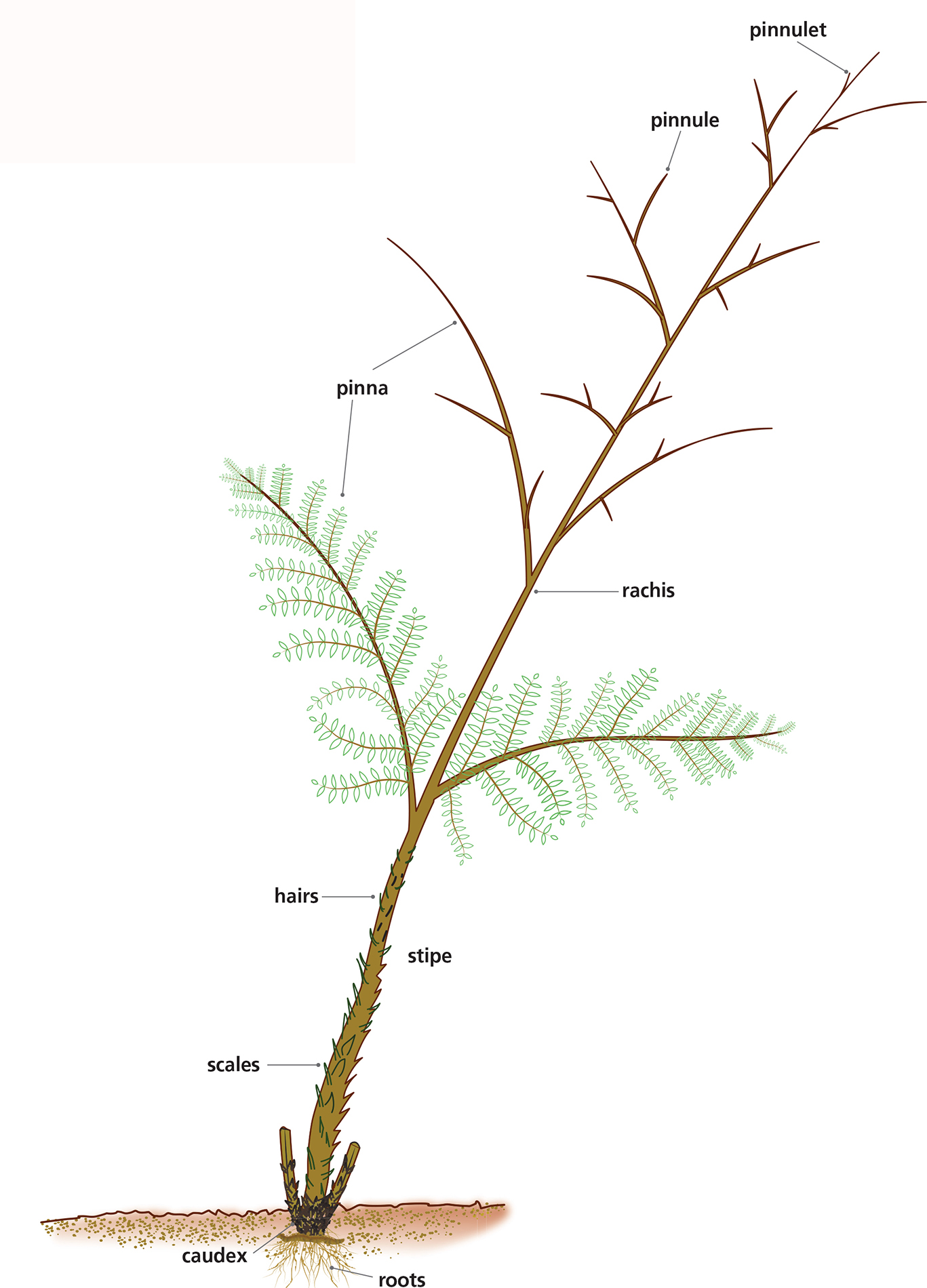

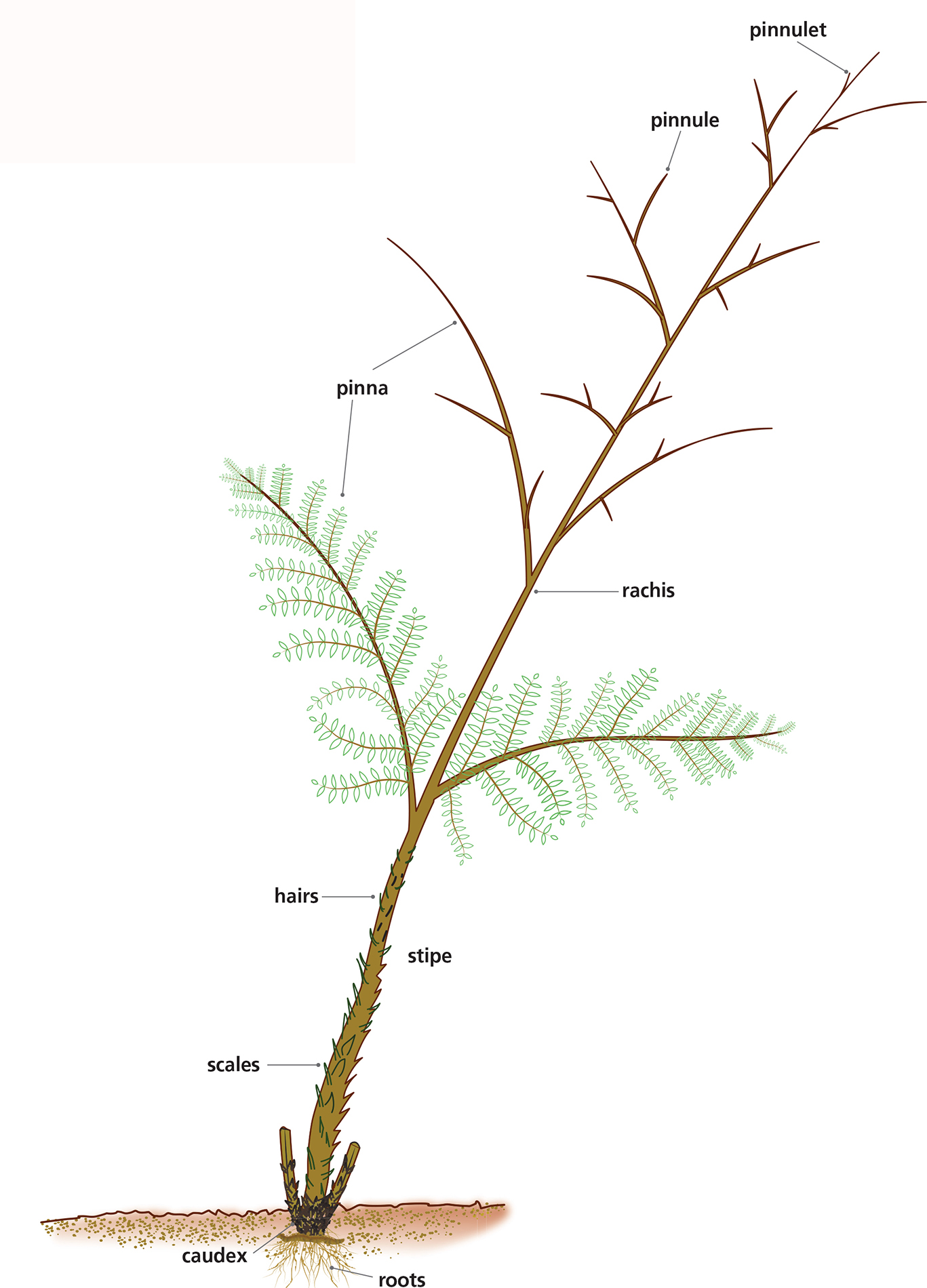

The standardized typical leaf (frond) consists of a stem (stipe) and leafy portion (lamina), supported on a midrib (rachis) which can branch.

Ferns do not produce flowers, but reproduce by spores, normally produced on the underside of the frond. In almost all species the fronds unfurl a process called circinate vernation. Before the recent DNA discoveries, ferns were classed as vascular cryptogams, vascular because the fronds have vascular tissue like a flowering plant. Mosses, liverworts and algae do not. Ferns vary greatly in their frond form, but the stylized illustration shown here gives a good idea of their general appearance as well as naming their component parts.

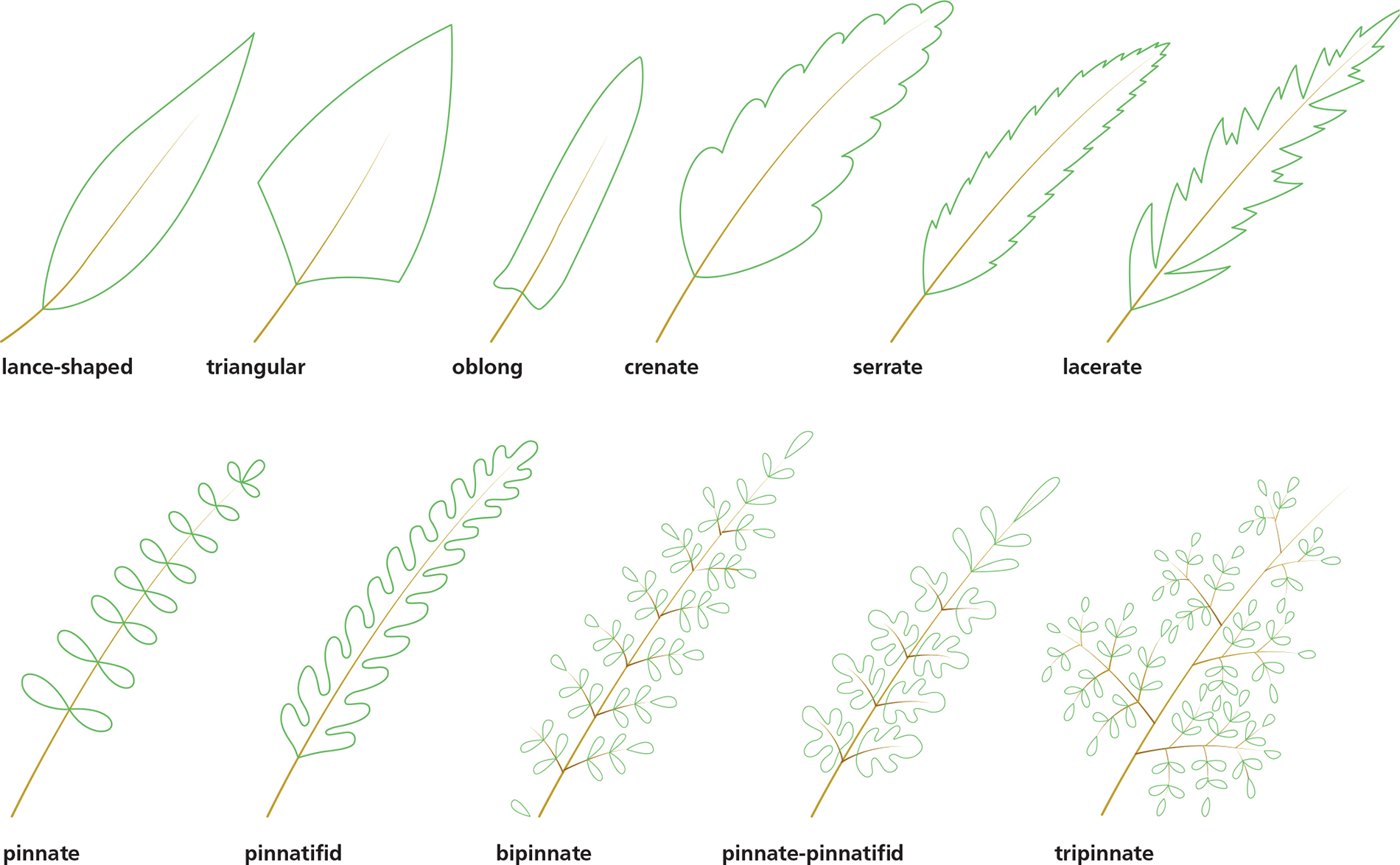

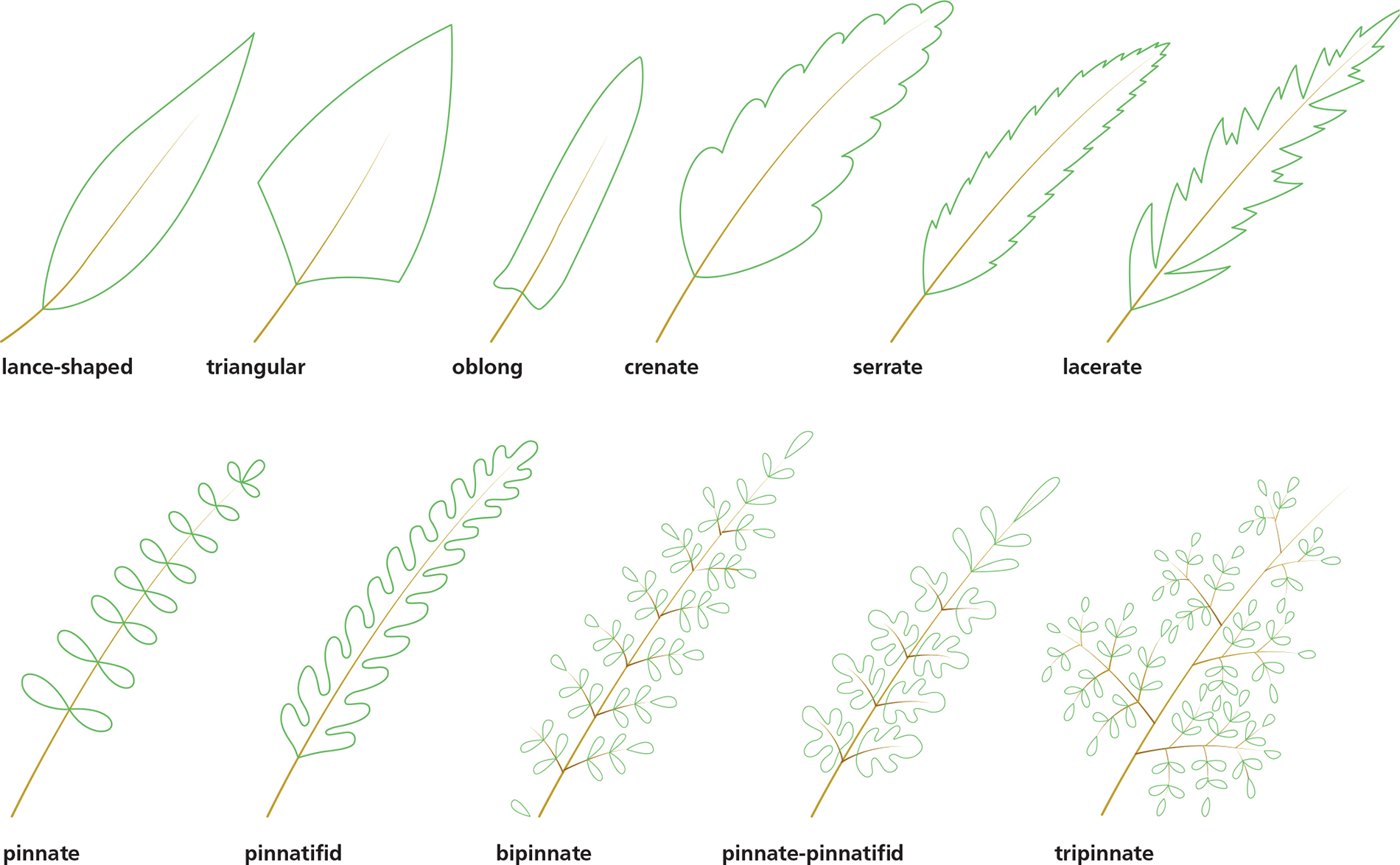

Frond shapes.

An example of a tripinnate frond Polystichum setiferum Tripinnatum.

For identification purposes the frond must be described; the basic classification of the terms used in describing a frond are shown in this illustration, others are explained in the Glossary.