SOUND

INTRODUCTION TO PHYSICS

SOUND

EDITED BY SHERMAN HOLLAR

Published in 2013 by Britannica Educational Publishing

(a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010.

Copyright 2013 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Educational Services materials copyright 2013 Rosen Educational Services, LLC. All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services.

For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering: Director, Core Reference Group, Encyclopdia Britannica

Adam Augustyn: Assistant Manager, Encyclopdia Britannica

Anthony L. Green: Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Michael Anderson: Senior Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Andrea R. Field: Senior Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Sherman Hollar: Senior Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control

Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies

Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor

Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor

Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition

Rosen Educational Services

Jeanne Nagle: Senior Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Karen Huang: Photo Researcher

Brian Garvey: Designer, Cover Design

Introduction by Jeanne Nagle

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sound/edited by Sherman Hollar.

p. cm.(Introduction to physics)

In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.

Audience: 7 to 8

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61530-845-3 (eBook)

1. SoundJuvenile literature. I. Hollar, Sherman.

QC225.5.S664 2013

534dc23

2012010563

On the cover, p.3: A hand fingering the fretboard of an electric guitar. The position and pressure of fingers on the fret determines the tone and pitch of the sound made. iStockphoto.com/Anthony Brown

Cover (equations) iStockphoto.com/James Thew; pp. iStockphoto.com/CWLawrence; remaining interior background image Yakobchuk Vasyl/Shutterstock.com

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

S ound can mean different things to different people, depending on the situation. For instance, a train whistle might let an excited traveler at a railway station know he or she is about to leave on a long-awaited trip. For someone walking near train tracks, however, that same whistle serves as a warning that an engine is coming and the person needs to get out of its path. Likewise, a dog barking at night might make the poochs owner feel safe from burglars, but may simply annoy neighbors trying to sleep.

Regardless of the situation or interpretation, all sounds have things in common, mainly how they are produced and how they are processed by those who hear them. This book reveals the physics behind sound creation and details the various properties of sound. It also reveals that the fleshy bits of the human ear, visible on either side of a persons head, are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the ears form and function. Readers are taken on a virtual journey through the human ear for an explanation of how sound is heard. Also discussed is the field of acoustics.

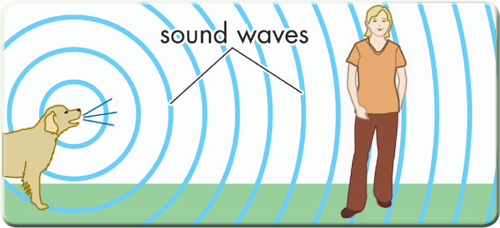

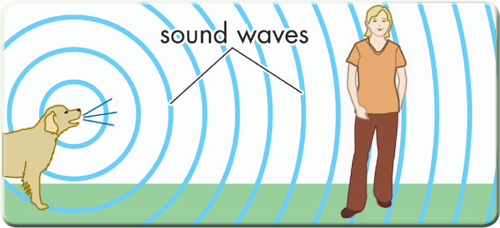

Sound is produced in waves caused by vibrations. The movement of the vibration pushes and pulls air molecules, which crowd together and form invisible ripples in the air. These ripples, called compression waves, travel from the source of the vibration in all directions until they reach a pair of ears, which translate the vibrations into sound.

Strength and frequency (how quickly one complete vibration occurs) each affect how sound is heard. How strong a vibration is determines whether a sound is loud or softthe stronger it is, the louder. Frequency influences pitch, which is how high or low a sound is.

Sometimes a solid object blocks the path of sound waves traveling through the air. Sound is easily reflected from flat surfaces, meaning that the sound waves reflect off of the object and turn back toward the source. Reflection explains why there is an echo when a person shouts into a canyon that has flat, smooth walls. Reflecting off of curved objects restricts the paths that waves can take, thereby focusing sound as it travels from the source.

The curved shape of part of the outer human ear known as the external auditory meatus, or ear canal, helps focus sound as it is received. Sound waves journey down the ear canal to a membrane called the eardrum. Waves striking the eardrum cause it to vibrate. From there, sound waves travel to the middle ear, where they are passed along a series of three small bones called ossicles and strike another membrane called the round window. Finally, sound moves into the inner ear to the shell-like cochlea, which houses the organ of Corti. Covered in nerve endings that look like tiny hairs, the organ of Corti sends electrical impulses to the brain, where sound is identified.

There are many kinds of sounds, and various ways to interpret those sounds. But, as this book explains, the physics of sound are pretty straightforwardas well as quite interesting.

CHAPTER 1

MAKING SOUND

E very kind of sound is produced by vibration. The sound source may be a violin, an automobile horn, or a barking dog. Whatever it is, some part of it is vibrating while it is producing sound. The vibrations from the source disturb the air in such a way that sound waves are produced. These waves travel out in all directions, expanding in a balloonlike fashion from the source of the sound. If the waves happen to reach someones ear, they set up vibrations that are perceived as sound.

Sound, then, depends on three things. There must be a vibrating source to set up sound waves, a medium (such as air) to carry the waves, and a receiver to detect them. Sound waves cannot travel through a vacuum.

There is an age-old question concerning the definition of sound. If a tree falls in a forest far from any sound detector (such as a human ear or a microphone), does the trees crash make any noise? The answer, of course, depends on how sound is defined. If it is thought of as the waves that are carried by the air, the answer is yeswherever there are sound waves there is sound. However, if sound is defined subjectively, as a sensation in the ear, for example, the answer must be no. In that case sound does not exist unless there is a receiver present to detect it. The two definitions are equally correct.

Next page