THE LOVE CHAPTER

The Meaning of First Corinthians 13

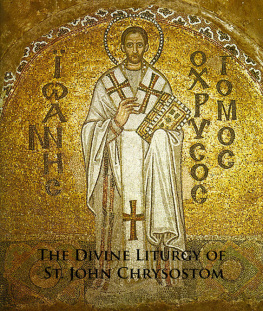

ST. JOHN CHRYSOSTOM

Foreword by Frederica Mathewes-Green

CONTEMPORARY ENGLISH EDITION

PARACLETE PRESS

BREWSTER, MASSACHUSETTS

The Love Chapter: The Meaning of First Corinthians 13

Copyright 2010 by Paraclete Press, Inc.

ISBN 978-1-55725-668-3

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989 by the Division of Education of the National Council of Churches of Christ in the U.S.A., and are used by permission.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

John Chrysostom, Saint, d. 407.

The love chapter : the meaning of First Corinthians 13 / St. John Chrysostom ; foreword by Frederica Mathewes-Green.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-55725-668-3

1. Bible. N.T. Corinthians, 1st, XIII--Commentaries. 2. Love--Biblical teaching. I. Title.

BR65.C45L68 2010

227.207--dc22

2009041562

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in an electronic retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Published by Paraclete Press

Brewster, Massachusetts

www.paracletepress.com

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

CONTENTS

CHAPTERS

H e was not imposing, they sayshort of stature, balding, and with a puny, if not emaciated, build. In a mosaic portrait high on a wall inside the great church of Constantinople, Hagia Sophia, he stands in white Eucharistic vestments, holding a book of the Gospels bound in gold. For centuries this image was buried under a thick coat of plaster; when Muslims conquered the city in 1453 and changed its name to Istanbul, all representational Christian art was suppressed. For centuries the building served as a mosque, but in 1935 it was converted into a museum, and images of Christ and his saints began to be released from their plaster shrouds. St. Johns icon now looms above the site where, as bishop of Constantinople, he preached the sermons that earned him the name Chrysostomos, meaning Golden Mouth.

To a modern reader, such an accolade suggests lavish and lofty prose, studded with ornamental flourishes. St. Johns style of expression comes as a surprise, in that case, for he is brisk and to-the-point. He plunges into the biblical text and examines it verse by verse, word by word, dispatching each topic as it arises. Rather than utilizing the language of self-conscious aesthetic effect, he speaks as if he is presenting one side of a debate. He is a paragon of preaching that is clear and persuasive, rather than merely momentarily inspirational.

He could certainly preach at great length, as well. In his book The Name of Jesus, Irne Hausherr recounts how Chrysostom once presented a series On the Changing of Names, as in Saul becoming Paul, and Simon becoming Peter. The introductory parts in particular were prolonged until the audience began to complain, Hausherr writes. By the end of the first homily, St. John had only just arrived at a statement of the central question: Why were the names of some figures in Scripture changed? In the second sermon, he continued to explore the subject, setting forth examples and refining the question. The third homily began with a defense against those who had been complaining that he spent too long introducing a subject; this defense occupied half the sermons length. We form an impression of St. John as one whose mind was ever busy, for whom the world and the Scriptures offered a limitless expanse for exploration.

The fact that audience reactions sometimes appear in his works suggests that to some extent we are reading a transcription of what he said, rather than a polished literary effort. In that case, his familiarity with the Bible becomes even more impressive, as he leaps from the Psalms to the Pentateuch to the letters of St. Paul, bringing forth themes that tie the whole of Scripture together. That he was able to do this with no tools at his disposal except hand-lettered texts makes the thoroughness of his knowledge all the more impressive. We who can leap through the Bible with a computer program have probably not digested it, or memorized it, as thoroughly as St. John had.

The sermons collected here, on the thirteenth chapter of First Corinthians, present a wonderful snapshot of St. John Chrysostoms usual work. Characteristically, he asks questions; he fearlessly sets forth questions that any Christian, or even a skeptic, might offer, and he deals with them squarely. His style is not to blur, avoid, and emotionalize. When he speaks about the Scriptures, he speaks clearly, straightforwardly, with an utter confidence in Gods goodness and justice. It is the kind of preaching that makes its hearers stronger, the kind that makes folks brave.

As was true of St. Paul, St. John Chrysostom was not impressive in appearance, but his words were with power. He had more than one conflict with the imperial court, as he chastised the wealthy and powerful for their self-indulgence and lack of care for the poor. (Chrysostom himself lived a simple life, despite his high ecclesiastical rank; in his first year as bishop he saved enough money from his personal expenses to build a hospital for the poor.) The conflicts between church and state that have resounded through the centuries were vividly displayed in St. Johns life. Angered at his sermons against ostentation in womens dress, the Empress intrigued to have St. John exiled from the city. He was brought back to great rejoicing among the people, but two months later the Empress unveiled a statue of herself, made of silver, in the square before the church. The accompanying celebrations interfered with worship services, and when Chrysostom protested he was exiled again. Driven from place to place, forced to march despite exhaustion and illness, exposed to wind and rain, tormented by his guards, St. John Chrysostom succumbed to death on September 14, 407.

It is recorded that his last words were, Glory be to God for all things. His steadfast determination to praise God, come what may, provides a valuable background for these writings on the nature of love and its superlative role in Gods kingdom. Thanks to its rough treatment over the years, his icon in Hagia Sophia is missing some of its mosaic tiles, and a scattering of places shows instead white plaster peeking through. It looks like light; it looks as if the visage of this saint is shimmering, ready to give way to the light that lies within. In this, as in everything else, St. John provides us with an example, a hope, and a guide.

Frederica Mathewes-Green

If I speak in the tongues of mortals and of angels, but do not have love, I am a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal. And if I have prophetic powers, and understand all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have all faith, so as to remove mountains, but do not have love, I am nothing. If I give away all my possessions, and if I hand over my body so that I may boast, but do not have love, I gain nothing.

Next page

CONTENTS

CONTENTS