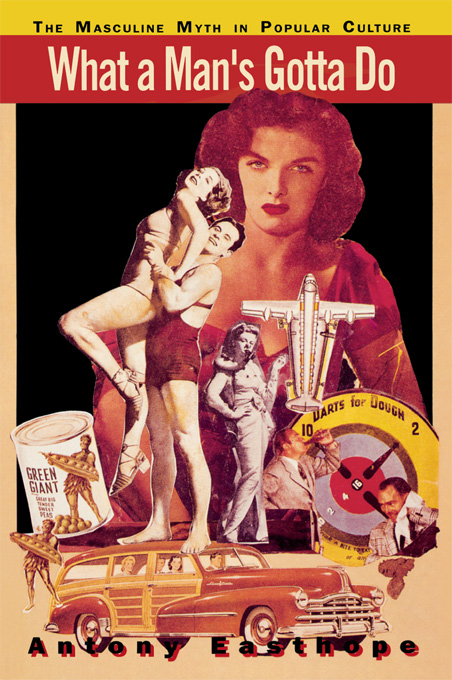

Published in 1990 by Unwin Hyman

Paperback Reprinted in 1992 by

Routledge

An imprint of Routledge, Chapman and Hall, Inc.

29 West 35 Street

New York, NY 10001

Routledge

11 New Fetter Lane

London EC4P 4EE

Copyright 1986, 1990 by Antony Easthope

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Easthope, Antony.

What a mans gotta do: the masculine myth in popular culture/Antony Easthope

p. cm.

Reprint. Originally published: London: Paladin Grafton Books, 1986.

Includes bibliographical references (p.

ISBN 0044457391

ISBN 0415906385 (pbk.)

1. Men in popular culture. 2. Men Psychology. 3. Masculinity (Psychology) I. Title. II. Title: What a mans gotta do.

[HQ1090.E281990]

305.31dc20

90-12167

CIP

British Library Cataloguing information also available

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank Rob Lapsley and Mike Westlake for criticism and ideas over a period of time that have contributed materially to all parts of this book. In addition I am grateful for discussions, containing both agreement and disagreement, with Jonathan Dollimore, Caroline Henton, Toril Moi and Alan Sinfield.

I would also like to acknowledge the help of the men and women I have worked with for some years in the area of cultural studies Margaret Beetham, Stewart Crehan, Sue Furniss, Elspeth Graham, Alf Louvre, Tony Martin and Pam Watts. Of course what goes into a book is one thing and what comes out of it is another.

I am also grateful to the following for giving permission for the reproduction of copyright material:

the Staatliche Museum, Berlin; Galleria dellAccademia, Florence; the Priests of the Sacred Heart, Hales Corners, Wisconsin; Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan; Martin Kemp and his book Leonardo da Vinci, published by J. M. Dent & Sons; Philip Morris Ltd; All-Sport; Daily Mail; Greenall Whitley Ltd; Daily Express; Thames Television International; Daily Telegraph; Associated Press; Popperfoto; Robert Graves; The Sun; ATV Music Ltd and Point Music Ltd; Michael Linnit Ltd; TV Times; Virgin Music (Publishers) Ltd; Kiss Me Deadly 1953 by E. P. Dutton & Co, reprinted by permission of New English Library Ltd.

For Lilian, Carol-Ann, Diane, Annabeth,

Catherine and Kelynge

INTRODUCTION

So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them.

Genesis 1

It is time to try to speak about masculinity, about what it is and how it works. This collection of essays looks at the images of masculinity put forward by the media today and analyses the myth of masculinity expressed through them.

Despite all that has been written over the past twenty years on femininity and feminism, masculinity has stayed pretty well concealed. This has always been its ruse in order to hold on to its power.

Masculinity tries to stay invisible by passing itself off as normal and universal. Words such as man and mankind, used to signify the human species, treat masculinity as if it covered everyone. The God of Genesis is supposed to be all-powerful and present everywhere. He first makes man in his own masculine image before going on to create male and female. If masculinity can present itself as normal it automatically makes the feminine seem deviant and different.

In trying to define masculinity this book has a political aim. If masculinity can be shown to have its own particular identity and structure then it cant any longer claim to be universal.

An ancient myth of masculinity, going back to the Greek gods of the sun, equates maleness with light. In Genesis there are certainly men and women but only because he created them. Masculinity has always tried to be present everywhere as the source of everything, and this is what makes it hard to write about. Masculinity has to be unmasked, separated from the role it wants to play by pretending to be the human, the normal, the social.

Two things now make it possible to define masculinity in a critical way, just as they make it politically necessary as well. The first is the revival of the womens movement since the 1960s. By the very fact of asserting the rights of women and the claims of femininity the womens movement has put masculinity in question and suggested it has its own particular identity (competitive, aggressive, violent, etc.). In the same period gay politics has openly challenged the idea of masculinity that is promoted on all sides as normal and universal.

Feminist and gay accounts have begun to make masculinity visible. But, written from a position outside and against masculinity, they too often treat masculinity as a source of oppression. Ironically, this is just how masculinity has always wanted to be treated as the origin for everything, the light we all need to see by, the air we all have to breathe. The task of analysing masculinity and explaining how it works has been overlooked.

Popular Culture

If masculinity is not in fact universal, where is it? The Masculine Myth takes the version which saturates popular culture today, both British and American, in films, advertising, newspaper stories, popular songs, childrens comics. This is the dominant myth of masculinity, the one inherited from the patriarchal tradition. Here it is examined in twenty-two sections. Some are long, some short, but all look at an example of how popular culture portrays men and tries to appeal to them.

Clearly these are masculine fantasies, fantasies of masculinity. When I enjoy a Robert Redford film I imagine Im Robert Redford but I know Im not really. Men in fact live the dominant myth of masculinity unevenly, often resisting it. But as a social force popular culture cannot be escaped. And it provides a solid base of evidence from which to discuss masculinity.

Gender can be defined in three ways: as the body; as our social roles of male and female; as the way we internalize and live out these roles. To define masculinity in terms of the physical apparatus, the male genitals, doesnt get you very far. Sociologists have undertaken important work on the second way of defining masculinity, that is, in terms of male gender roles. But their writing about male behaviour and male attitudes tends to be too descriptive. It relies a great deal on interviews and what men are consciously prepared to admit about themselves. Sociological work does not look at masculinity from the inside, at the way social roles are recreated and lived imaginatively by individuals.

When I was born I did not know whether I was going to be Chinese, English, or Navajo Indian, but still nature had equipped me, like everyone else, with the biological potential to live and reproduce in any of those societies. But biology is not enough. Every society assigns new arrivals particular roles, including gender roles, which they have to learn. The little animal born into a human society becomes a socialized individual in a remarkably short time. Babies born in England go off to school five years later to spend most of the day away from their parents. They can do that because they have internalized and come to live for themselves the roles of the parent society. This process of internalizing is both conscious and unconscious. To understand it fully we need to be able to analyse the unconscious.