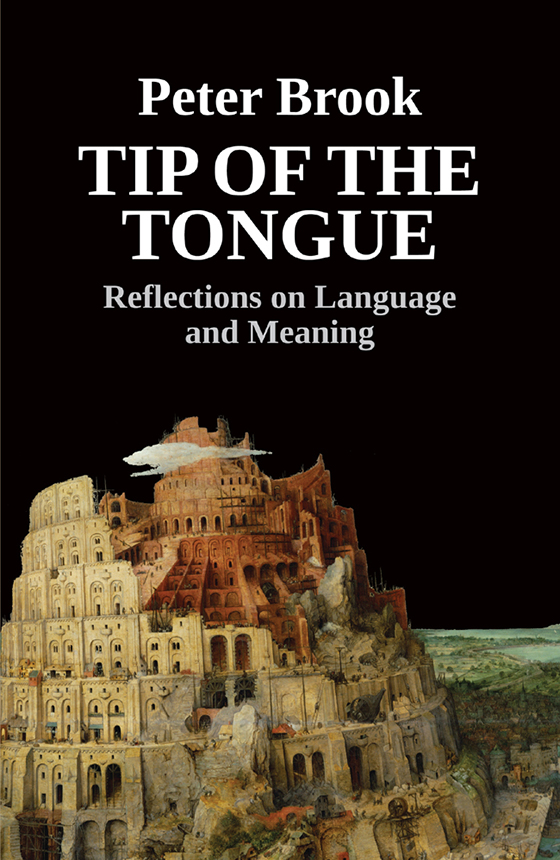

Peter Brook

TIP OF THE

TONGUE

Reflections on Language

and Meaning

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

To all those who over the years have stimulated the questioning and the experiences I describe.

This cannot be dedicated to one personto you all with gratitude.

Contents

Prologue

A long time ago when I was very young, a voice hidden deep within me whispered, Dont take anything for granted. Go and see for yourself. This little nagging murmur has led me to so many journeys, so many explorations, trying to live together multiple lives, from the sublime to the ridiculous. Always the need has been to stay in the concrete, the practical, the everyday, so as to find hints of the invisible through the visible. The infinite levels in Shakespeare, for instance, make his works a skyscraper.

But what are levels, what is quality? What is shallow, what is deep? What changes, what always stays still?

This can now lead us together through manyforms, at many times, in many places. To begin with, what is a word?

If we say to a child, Be good, the word good has its everyday commonplace meaning. If we rise above the ground level, the word good brings us to finer and finer shades of goodness. Even more so in FrenchSoyez sage, the parents say to their children, using sage, a word for wisdom. There are so many words that contain such promises. A divine evening. Divine belongs to the sky. To use divine casually makes the sacred lose all its meaning.

In the pages that follow, we will explore together the sometimes comic and often subtle differences between two languages that have lived together for so longFrench and English.

With William the Conqueror, the Latin-based language penetrated into English and vastly enriched its vocabulary. For us, theNorman invasion was a blessing. On the other hand, the Anglo-Saxon idiom seemingly never penetrated beyond Agincourt. Thanks to this, French, with a much smaller vocabulary, became a vehicle for pure and crystal-clear thought. I must, however, warn the reader that all comments on the French language in this book come necessarily from an Anglo-Saxon point of view.

After nearly half a century of living in France, when I ask for something, clearly, in a shop, the person serving me winces and immediately answers me in English. Either it is fear of not understanding the foreigner or else the pain of hearing their fine language mangled, its precise rules ignored. This has been a starting point for relishing the difference between two languages which are like chalk and cheese.

Over the years, I have wondered what is the mysterious relationship between a word and its real meaning. Words are often a necessity.Words, like chairs and tables, are necessary tools for navigating the everyday world. But it is all too easy to let the word itself take first place. The essence is meaning. Silence already has a meaning, meaning that is searching to be recognised through a world of changing forms and sounds.

Our lazy habit is to generalise. We will discover that, much as the atomonce openedcontains a universe, in the same way if we linger fondly within a phrase, we find within each word and every syllable that the resonances are never twice the same.

PART ONE

Words Words Words

When the very first pre-Neanderthal man slammed two stones together, scraped them to make a sharp edge that could cut, he made a grunt. Centuries went by as he painfully developed his tools, and at the same time he developed his grunts and growls into early forms of speech.

He needed to communicate his strivings to another human creature. Amongst the first fragments of meaning came syllables that corresponded to good and no good. As he discovered that there were many steps in between these two, they became targets, and the way towards them became better or worse. Time crept by, and the sense of a goal, and of the long distance to be travelled to approach them, made betteror worse an instant encouragement to continue or a source of anger or despair. Better or worse became all that was needed for activity to continue.

Then for a million reasons, religion appeared, and at once the great unattainable became good and bad. God became the unattainable, bad became evil. From evil it was a short and ever-so-useful step to the Devil. And so evil became incarnated into demons and good into angels leading to God.

From this came the greatest of human discoveries, that at every moment in every manifestation, every form, every action, better or worse were the great motors of evolution and transformation.

Then it became clear that there are levels for everything. For the artisan, for the artist, for the contemplative. At any moment there is a possibility of better and an inevitable giving-waygradually mankind becameaware of levelssomething expressed by a ladder with angels helping man up and devils making him slip and dragging him down.

Today, the image that presents itself is the skyscraper. Sometimes the elevators work, but at other times (as during and after a tornado) one must climb on foot. The effort is enormous, more and more painful, and for each one of us there is a time when no more effort is possible. One looks at the number of the floor one has reached and realises how tiny it is compared with the number of floors to be climbed before one emerges on to the open gallery at the top, with its vision of the sky and its brilliant light. And from every floor the view changesfor the better: the field of vision is wider and wider. More can be seen and understood. Better to be high up, worse to be in the dark dampness of the basement.

Now we see that in every activity in life a sense of levels is present in us. We need to gono further than a single word. And within it, an endless scale of finer or coarser vibration, of finer or coarser meanings.

Tip of the Tongue

Je ne comprends pas ce quil dit. Pas un mot. (I cant understand a word he says.) This reaction from someone in the audience at the first preview of our first production in Paris with our international group of actors left me speechless.

The actor had come to us from the Royal Shakespeare Company with perfectly trained projection and diction. I stood at the back of the stalls and could follow every syllable. If I could understand, why couldnt the French? It took me a long time to discover the solution to this enigma.

Where did it all begin? With the creation in Paris in 1970 of the International Centre for Theatre Research. Three years had gone byfor a group made of actors from many parts of the world, three years of exploring sounds with our tongues, our throats and our chests. Our own languages had been put aside, or rather had served as fascinating elements of exchangeJapanese against Bambara, English into Portuguese, Farsi or Armenian. We had gone back to the earliest languagesAvesta, Ancient Greekand the adventurous poet Ted Hughes had written for us a new language of his own, Orghast, in which the meaning of a word was uniquely carried by its shape and sound. We never worked in a theatre, always playing in fresh, unexpected situations, from supermarkets to ancient ruins and African villages.

We returned to Paris to reopen a forgotten theatre, the Bouffes du Nord, and this time all the words came from Shakespeare. We were preparing to play Timon of Athens in French. It was here that the fundamental difference between French and Englishsuddenly became painfully clear. A French group was joining us for the first time, and our actors were fascinated. For our group, it was a new experience to be with the French performers, and everyone welcomed the chance of being shaken out of their usual habits.