Table of Contents

One

A Midsummer Nights Dream

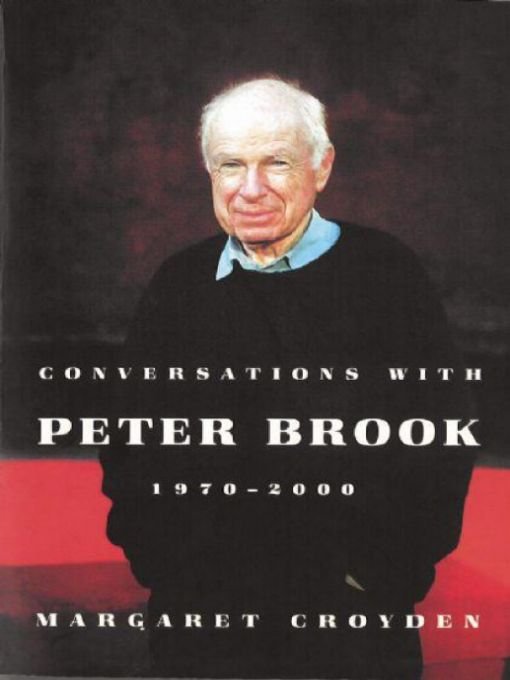

Peter Brook burst into New York in 1971 with A Midsummer Nights Dream, five years after his Marat/Sade appeared on Broadway. Dream had received unanimous raves in London and was shortly to garner unqualified acclaim when it opened on Broadway. Critics and audiences embraced Brooks radical approach to a surprising degree, and soon Dream became a landmark in Shakespearean production. Departing from his dark period of King Lear and Marat/ Sade, Dream was a joyous celebration that created pride in performance and a newfound delight in theater itself for all who either performed in it or saw it. In its break with tradition, Brooks production, in all its visual beauty, opened up new possibilities for producing Shakespeare, and, in fact, it encouraged new and daring work by others.

Through the years, A Midsummer Nights Dream has meant dancing fairies, green woodlands, and gossamer wingsOberon, Titania, and Puck flitting about, casting their magic spells with sweet sentimentality. From David Garrick to Max Reinhardt, directors had leaned heavily upon this tradition of cloying romanticism, and few had had the temerity to break it. Finally, Peter Brook did. His Midsummer Nights Dream was a deliberate departure from conventioncontemporary in design, Freudian in tone, and, at the same time, faithful to the Shakespearean text. Here are no winged fairies, fake moons, or silver sequins, but a pristine and sensuous visiona joyful tribute to Shakespeares the poet, the lunatic, the lover.

Brook staged Dream on a brightly lighted, open white stage with galleries running around the top, a setting reminiscent of Shakespeares Globe, but one in which the fairies, dressed in nondescript gray satin slacks and shirts, played Richard Peaslees atonal music on bongo drums, tubular bells, and Elizabethan guitars, creating sound effects on washboards and metal sheets, as in the Chinese theater. On the side of the walls were firemans ladders, on which actors ran, jumped, and played.

Here the forest was not a place where the wild thyme grows; this forest had trees with white metal coils cast down from the galleries like fishing nets by capricious beefy male fairies to entangle the two pairs of Athenian lovers, who were dressed in tie-dyed pink-and-blue mod outfits.

Without makeup and wearing white satin cloaks, the entire company of playersdashing, energetic, and proudstarted the play to the sound of drums; as each made his entrance, he bowed to the audience to signify the beginning of the ceremony. Under the bright lights, the magic was made visible. Oberon and Puck were not earthbound, but flew through the air on trapezeslike sudden lightning flashes of yellow and purple, the colors of their costumesdispensing their love juice from a silver plate spinning on a jugglers stick. Titania, in striking green satin, was on a scarlet ostrich-feather bed that levitated in space like a swing. There the burly Ass with a Bert Lahr clowns nose, string undershirt, and workers clogs would bed the glamorous Queen like a fighter going into the ring. And at this climactic point, phallic jokes and ironic stage business were introduced to mark the union of this bizarre pair.

The ultimate magic was the sight of Oberon and Puck swinging through the air, throwing their magic western flowera diskto each other from the height of about thirty feet. At another point, Puck walked on stilts, and Oberon swung on a long rope suspended from the ceiling, his purple satin gown billowing in the air to celebrate the union of his queen with the Ass, while most of the rest of the company, to the tune of Mendelssohns Wedding March, pelted the entire wedding party with confetti and paper plates, leaving the mischievous Puck to clean up the mess with broom and shovel.

This Dream revealed the ambiguities of love, the uncertainties of sexual desire, the grotesque subconscious images, the lunacy and obsession of love. What fools these mortals be is, to be sure, an integral part of the play, but so is what visions have I seen, which underscores the essence of this amazing production.

In an interview in his handsome Paris apartment in 1971, Peter Brook, lounging in his stocking feet on a low orange couch and flanked on one wall by a stunning Afghan tapestry and on the other by his then four-year-old childs crepe-paper collage, recalled when he and Sally Jacobs, the set and costume designer, started work on Dream.

Q:How did the Dream project begin?

PB:Sally Jacobs and I started in New York. We said we were going to make a theatrical space in which theatricality could be celebrated. And that nothing was going to impose an actual shape on the story, nor would any of the costumes impose an interpretation on the actors. It would all be purely functional, in a theatrical way. The place had to be somewhere that told no story but enabled very difficult theatrical actions to be seen. So we had a place like a gymnasium, which told no storyit had to be whitein which people could be on wires, could be on the ground, could be in the air, could leap, swing, hang, fly, jump, and run. And that was the space.

Q:I understand that you always start work on a bare stage and that you sometimes want to keep it that way.

PB:Well, yes, we thought that. What would be wrong with a bare stage? Why should we put anything on it at all? And why should we have any costumes? Sally is the first personalthough shes a brilliant designer of costumes and sceneryto use, if this is whats right, working clothes. In USan experimental work about Vietnamshe scrapped a whole set of costumes in favor of jeans. So that at the dress rehearsal, actors, in working clothes, were closer to the basic reality of Vietnam, the subject of the piece. Here, we did start with a bare stage, and actors in working clothes, and we said, Whats wrong with that? Actors in jeans and sweaters. We rejected this in Dream for a very simple reason. Because there was nothing wrong with it, except that it was not joyful. The bare stage, the Stratford hall, was a rather negative statement. The actors in their own clothesthis was not the starting point of a celebration. We were making a celebration in Dream. We didnt want that great, stark, spare, empty desert. We wanted a small place. And we wanted a small luminous place. So we made a box.

Q:How did the rest of it fit inthe trapezes and all that?

PB:We wanted certain facilities in the box. We were not certain how it was going to be used, but they had to be there for people to jump and spin. So the instruments came into it. We used a million props in rehearsal, which we threw out, one by one, until we simplified it down to these few sticks. And then for the costumes, we said we did not want bare clothes, but brilliant and joyful clothes... Actors dress up because you can do more brilliant movements if you have a flying cloak; you can fly through the air more dazzlingly if you know that you are a streak of yellow moving through the air. Yet we didnt want any of those things to indicate, before we started, that this was the character of Puck, or this was the character of Titania. So, in fact, Titania was bright green, and Oberon was purple, and Puck was a streak of yellow. They were working clothes for performers trying to perform, proud of what they werethat is, performers enjoying performing in front of other people.