ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Nell Bernstein for her pioneering work with children whose parents are incarcerated and for graciously allowing us to include a quote from her landmark work, All Alone in the World: Children of the Incarcerated , by Nell Bernstein, published by The New Press, New York, New York, 2005.

A Set of Core Principles for Policy Development is used by permission of Dee Ann Newell. We are grateful to Dee Ann for her enthusiastic support and guidance in this project.

Children of Incarcerated Parents: A Bill of Rights is the work of the San Francisco Children of Incarcerated Parents Partnership (www.sfcipp.org), which is supported by the Zellerbach Family Foundation.

Design by Cliff Snyder

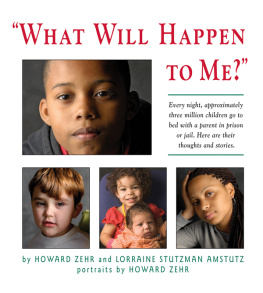

WHAT WILL HAPPEN TO ME?

Copyright 2011 by Good Books, Intercourse, PA 17534

International Standard Number: 978-1-56148-689-2

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2010012419

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner, except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, without permission.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Zehr, Howard.

What will happen to me? / by Howard Zehr and Lorraine Stutzman Amstutz ; portraits by Howard Zehr.

p. cm.

Every night, approximately three million children go to bed with a parent in prison or jail. Here are their thoughts and stories.

ISBN 978-1-56148-689-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Children of prisoners--United States. 2. Children of prisoners--Services for--United States. 3. Prisoners families--United States. I. Amstutz, Lorraine Stutzman. II. Title.

HV8886.U5Z44 2011

362.8295092273--dc22 | 2010012419 |

TABLE OF CONTENTS

A FEW WORDS TO BEGIN

M y mom is somewhereI dont know wherebut she isnt here with me. It cant be good because it seems like a big secret. Grandma says shes away getting an education, that she loves me, that shell be back when shes learned her lessons. What lessons? Why cant she learn them here, with me?

My teacher looks at me funny when the subject of parents comes up. The other kids whisper and say nasty things: Your mother was bad. Shes a crook.

When its parents day at school, the other kids bring their mom and dads. I bring Nana. Shes a lot older than the other adults.

I know other kids who are missing a parent, some of them both parents, but I feel something shameful about my mom. Im just not sure what it is.

I worry about her. I wonder whether Im like her. If shes done something bad, does that mean Ill follow in her footsteps? Did she leave because I did something bad?

I think about her a lot. I dream about her. What is she like? Is she safe? Do I really have a mother? Does she love me? Why isnt she here, taking care of me?

I feel alone. Sometimes I think Im the only kid like this.

In fact, there are at least three million other children in America in similar situations.

This book is about and, in a sense by, children who have one or both parents in prison. Some of the issues they name are faced by all children who have absent parents. But, there are special challenges and pains when a parent is in prison.

What Will Happen to Me? is also about, and for, those who are caregivers of such childrenthousands of grandparents who are raising these children, millions of teachers, school counselors, and social workers who interact with them daily.

Through the voices of these families come the challenges and hardships they face, but also the remarkable resilience and spirit they often demonstrate. Based on their experiences, the book suggests themes and strategies that may be helpful to caregivers and perhaps to the children, too.

ABOUT THIS BOOK

We have organized the book into three sections. The majority of the book, PART I , includes the faces and voices of children. PART II is especially for caregivers. It includes a few portraits and voices of grandparents, as well as some suggestions for understanding and responding to the needs of these children. PART III considers the justice issues raised by these families situations.

We began this project because we wanted to give voice and visibility to these often forgotten children who are so profoundly affected by circumstances and policies that do not take their needs into account. We interviewed and did photographic portraits of children of various ages in a number of communities across the country. From that material, we created an exhibit that is now available on loan through the Mennonite Central Committee Audiovisual Library. (See Suggested Resources , , for more information.)

As we got further into the project, we became more and more aware of the burden put on caregivers, especially family members and often grandparents, who take care of children whose parents are incarcerated.

The young people featured here are predominately children of color. While their numbers may be somewhat over-represented in this book when compared to the number of persons of color in the U.S., their presence generally reflects proportionately the overall reality of the prison population in this country. We believe that people of color are over-represented in prison primarily because of law enforcement and sentencing policies that impact communities of color most heavily. However, the impact of parental incarceration on children, no matter their race or cultural background, is profound, and many of the issues they face are universal.

OUR INTEREST IN THIS SUBJECT

The two of us who have undertaken this project have been colleagues in the field of restorative justice for many years, working with those who have offended, those who have been offended against, and their families. Howard has done several photo/interview books that present the voices and photos of victims and their families, and of life-sentenced prisoners (See Suggested Resources , ). Lorraines thesis (for the Masters in Social Work degree) focused on children with parents in prison.

OUR GRATITUDE

So many individuals and organizations have contributed to this project that it is hard to know where to begin and end. For financial support, we acknowledge the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the Fransen Foundation, the Victim Offender Mediation Association, and Joseph and Barbara Gascho. For financial support that helped make time to work on this project possible, we thank John and Kathyrn Fairfield and Ruth and Tim Jost. Individuals who contributed knowledge and connections include Jacqueline Shock, Nariman Elias, Michael Bischoff, Teya Sepinuck, and Erica Fricke. Organizations that collaborated or assisted in some way are The Center for Justice and Peacebuilding at Eastern Mennonite University, the Mennonite Central Committee U.S. Office on Peace and Justice, Arkansas Voices for the Children Left Behind, TOVA: Artistic Projects for Social Change, and the Council on Crime and Justice (Minneapolis).

We especially thank Dee Ann Newell for her enthusiastic support and advice throughout this project and for her indispensable assistance in developing strategies to reach the intended audiences.

Photographic projects with children are always challenging because of the confidentiality and permission issues they raise. We deeply appreciate the program staff and the parents and guardians who understood the value of this project and were willing to have their clients and loved ones participate.

Above all, we want to thank those young people and grandparents who so generously lent their voices.

HOWARD ZEHR LORRAINE STUTZMAN AMSTUTZ

P ART I