Between 300 and 150 million years ago, the mountain range would slowly erode away and bury itself in its own debris. By 150 million years ago, Colorado was as flat as a pool table. For a while it was dry, but then the area began to sink again and this time the sea came from the south, flooding the region yet again. The sea waxed and waned, and finally disappeared about 69 million years ago. One more million years passed, and a series of stresses related to weaknesses in the western part of the continent caused the Front Range to lunge out of the ground, folding and breaking through its overlying blanket of sedimentary rocks. This is when the rocks that would become flatirons were tilted up from their horizontal repose.

A few million years later the dinosaurs became extinct, wiped out by a global catastrophe. Between 65 and 37 million years ago, erosion of the Rockies again buried the mountains in their own debris, and by 37 million years ago the walk from Limon to Leadville would have been a smooth, gentle stroll. Then a spectacular eruption in the vicinity of the Collegiate Range spewed fiery death across the flat landscape. Minutes after the initial explosion, a superheated cloud of molten rock surged across the low-relief terrain and buried the landscape in twenty feet of instant rock. This stony casing lay on the landscape like a steel blanket.

But everything eventually gives way to the forces of erosion, and drainages began to cut deep channels in the layer of welded ash. Sometime about 10 million years ago, the whole region began to rise up again. This time the resistant granite and other tough rocks of the mountains core stood high while the softer rocks of the foothills and plains were more easily washed away and carried downstream to New Orleans. The flatirons were exhumed and shaped by erosion, and our present Rocky Mountain Front Range was literally unburied. Glacier-fed streams in the last 2 million years put the finishing touches on a landscape that is now called the Front Range urban corridor.

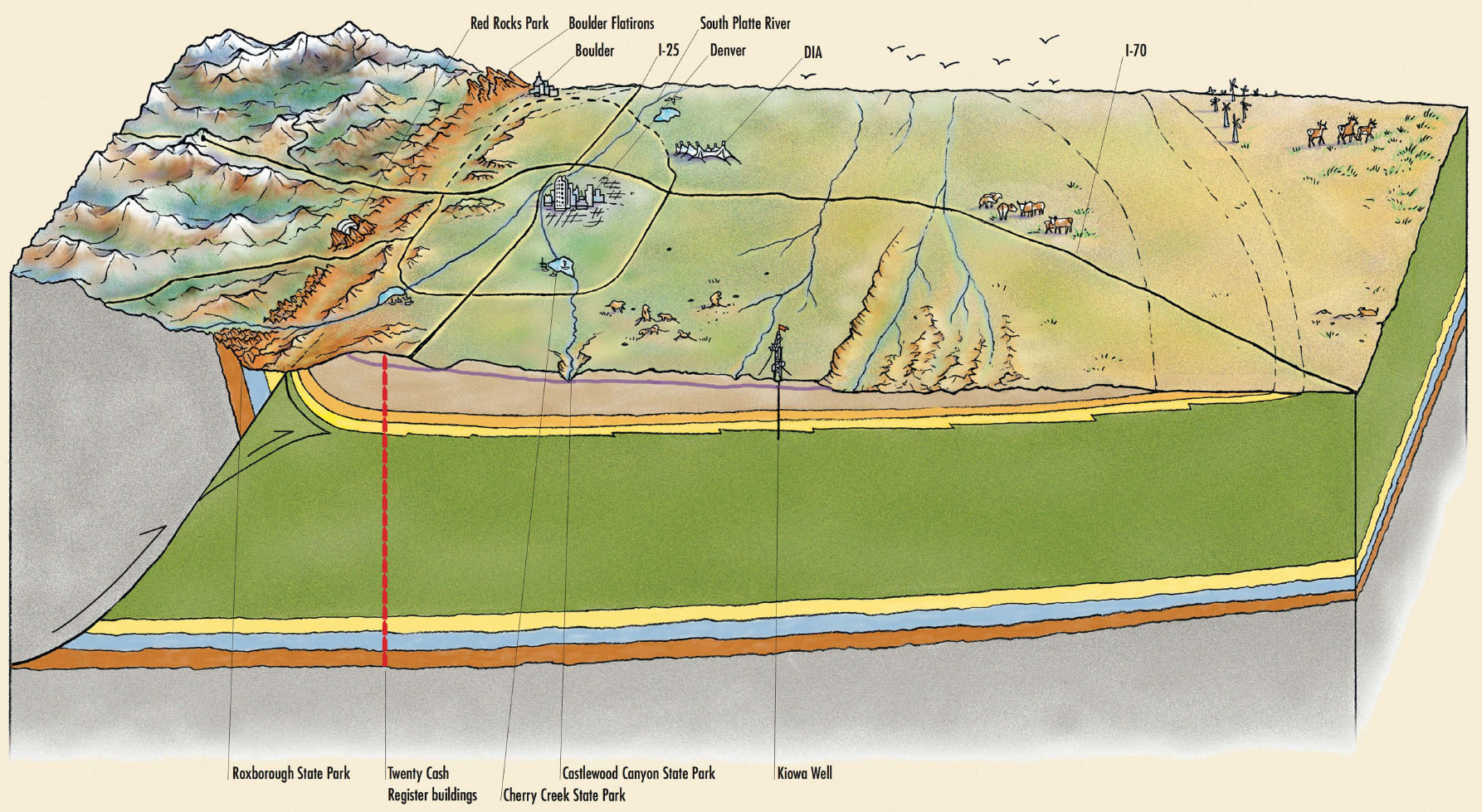

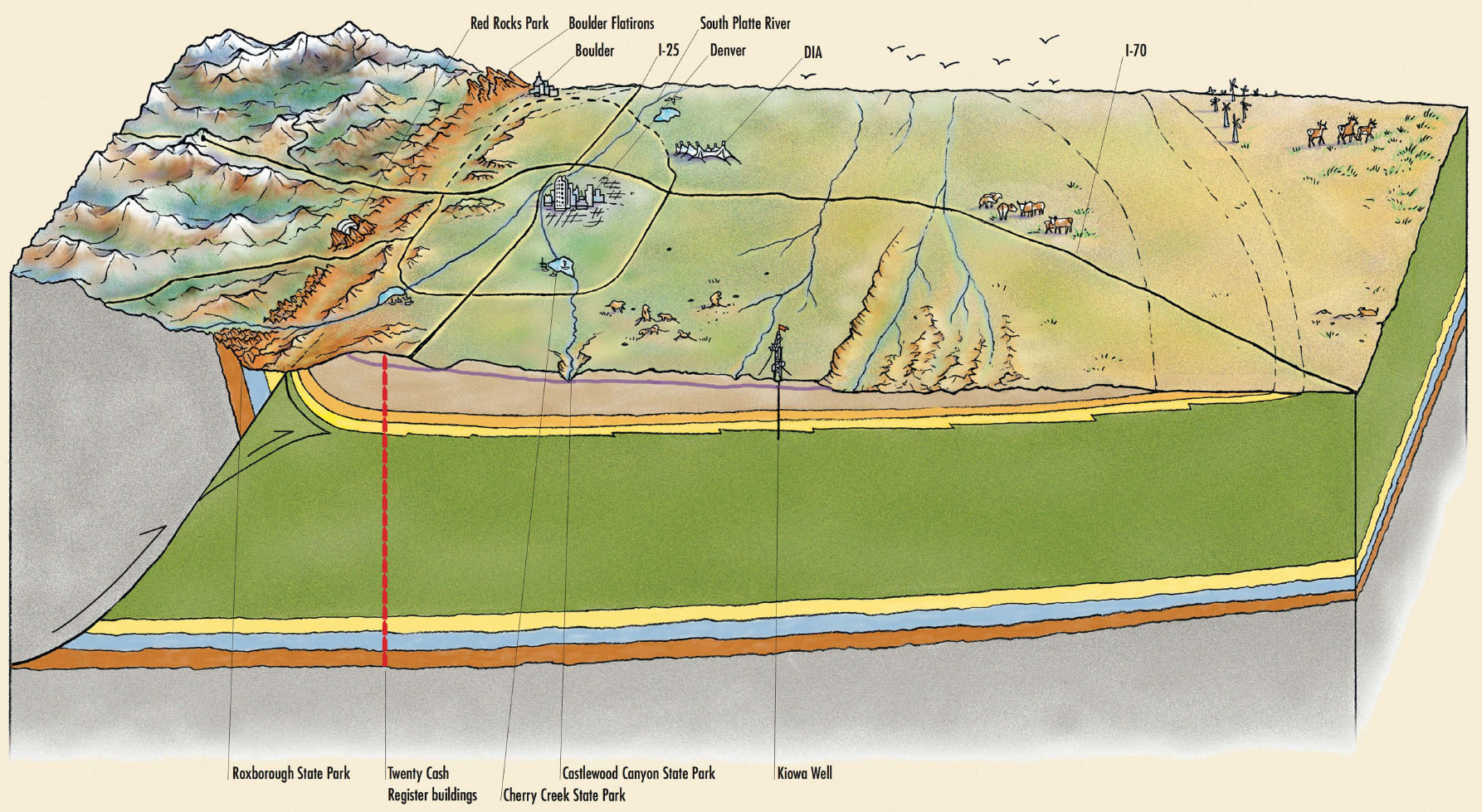

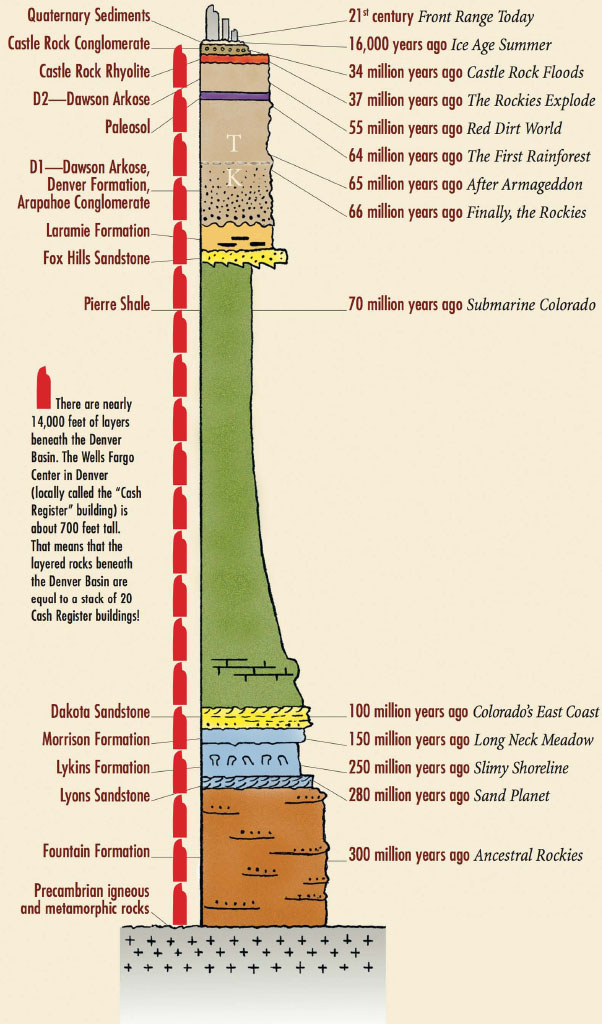

The geologic Denver Basin map shows where various rock layers are exposed at the surface in an onionlike pattern.

A sliced red onion is a good analogy for the structure of the Denver Basin.

Folding, Tilting, and FaultingPiece of Cake!

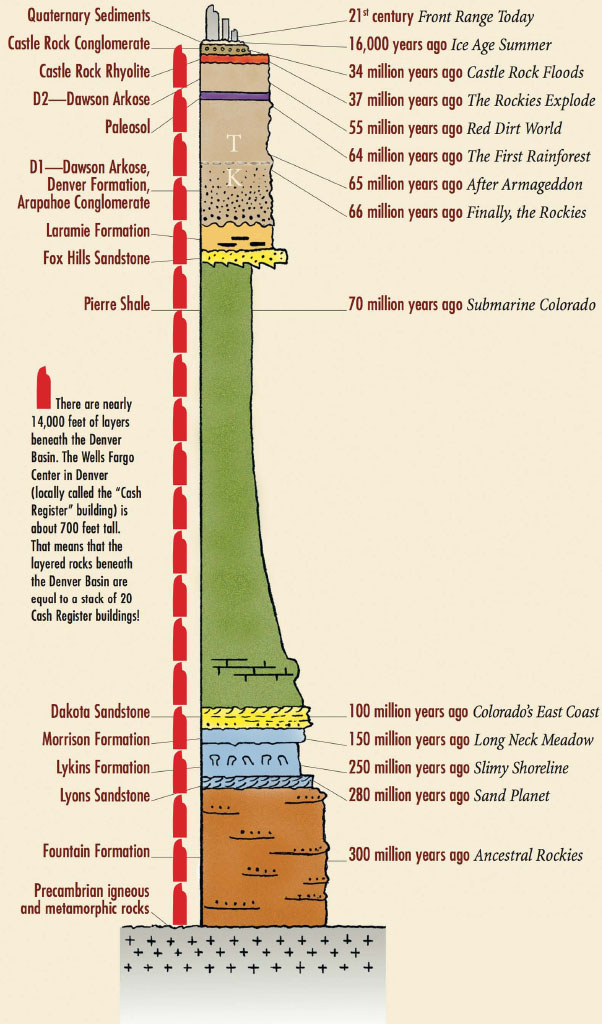

Imagine taking a giant knife and slicing through the Front Range landscape like it was a huge piece of cake. The block diagram to the right is the cake slice, and it shows how layers of rock lie deep beneath the regions cities and parks. It also shows how the folding, tilting, and faulting of these layers bring them to the surface, exposed for all to see.

The layers of rocks are called formations, and they are usually named after the area where they were first described. Thus, the rock layer just below downtown Denver is named the Denver Formation. The column to the far right shows all of the formations that were deposited in the center of the Denver Basin.

300 million years ago

Ancestral RockiesFountain Formation

BEST VIEWING SPOTS:

Garden of the Gods Park and Visitor Center

Roxborough State Park

Red Rocks Park and Amphitheatre

Boulder Flatirons

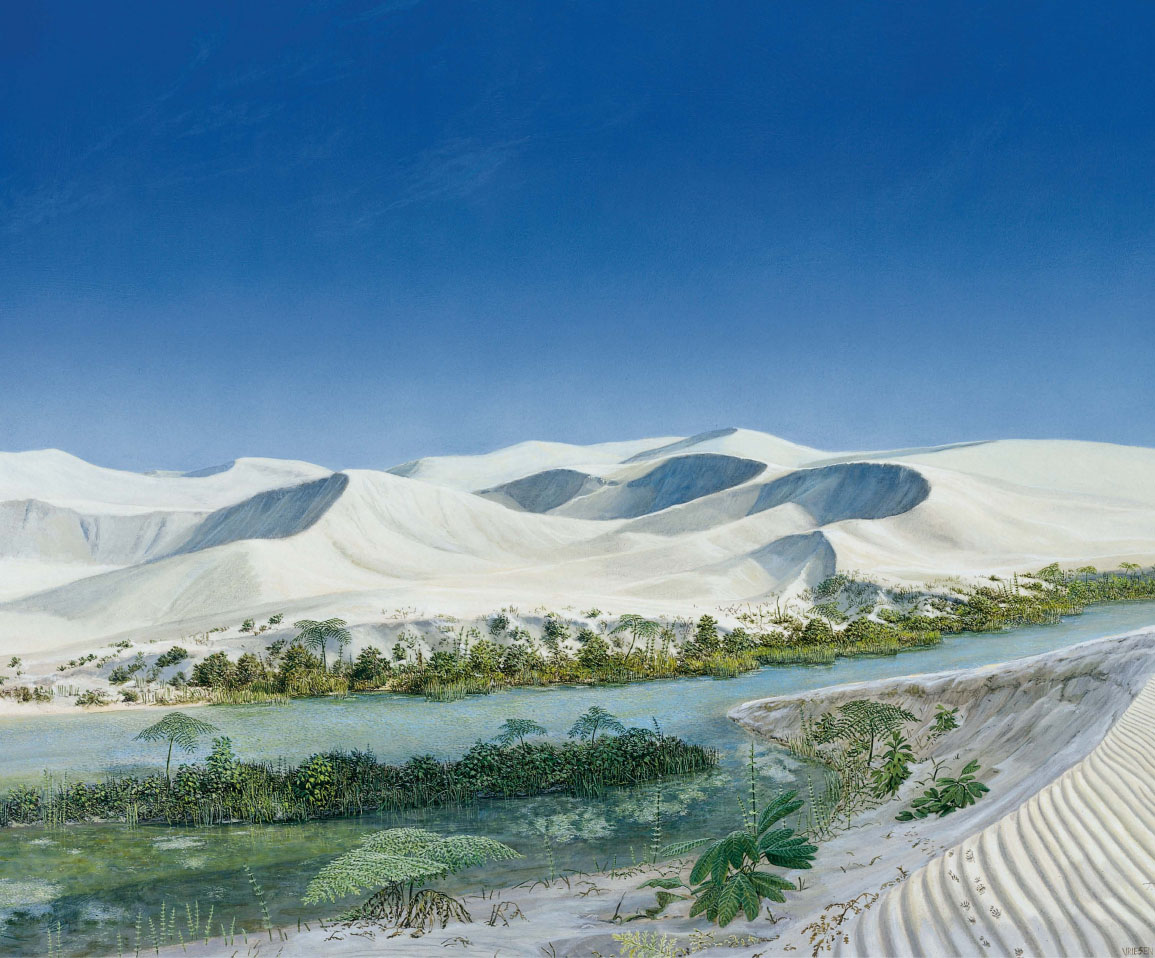

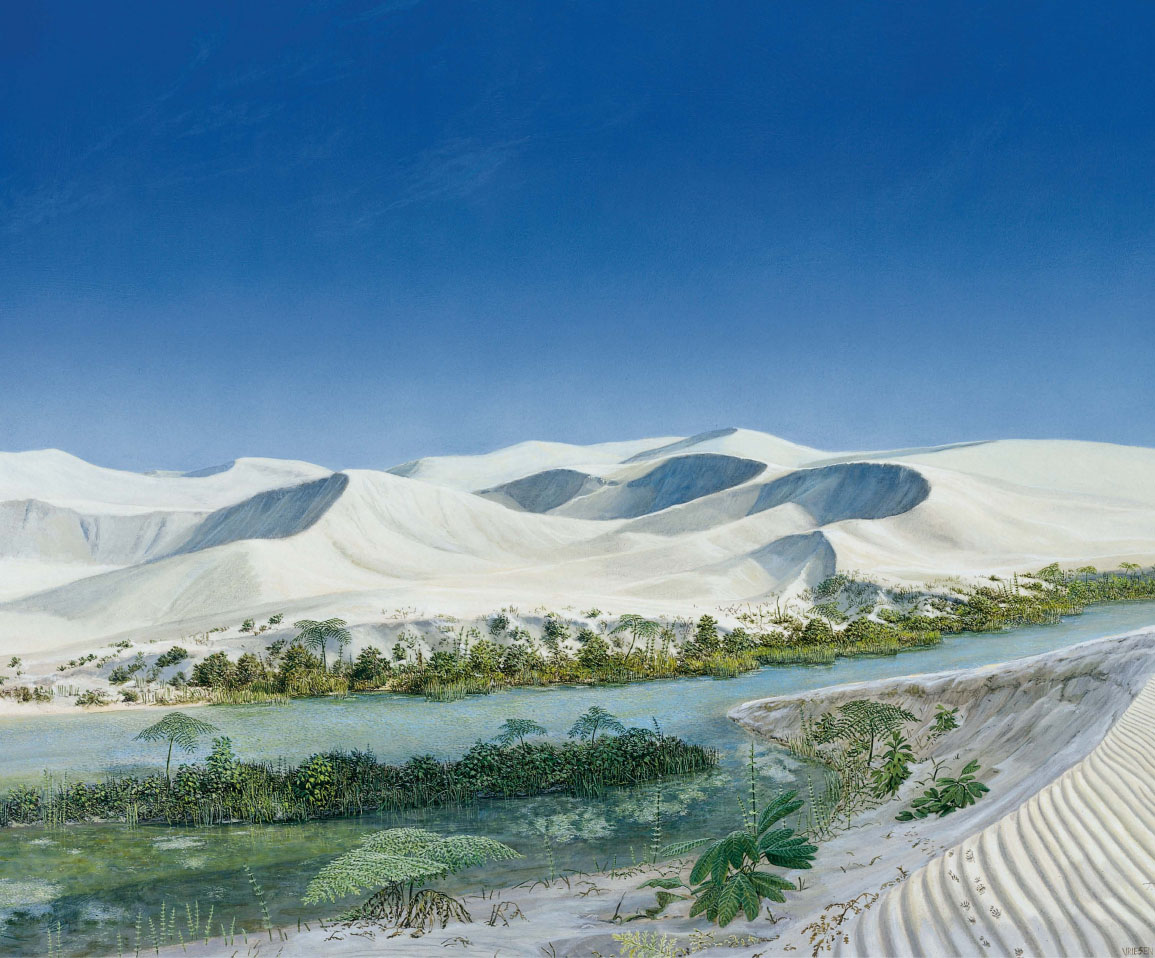

An utterly odd Colorado lies before you, where millipedes are as large as snowboards, and dinosaurs have not yet evolved. Colorado has mountains but it also has coastlines on both its eastern and western borders. These mountains are part of a range that stretches southeast from Colorado, extending all the way to Arkansas. The surrounding forests are relatively new to the planet and are completely different from the forests to come. Gravelly streams flowing off the mountains wind through forests of 100-foot-tall scale trees and giant relatives of the horsetail rush. Buzzing insects such as dragonflies are huge; while fin-backed protomammals, reptiles, and amphibians are relatively small.

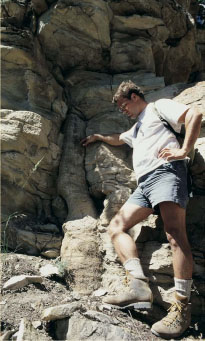

A giant horsetail tree fossilized in the cliffs high above Minturn, Colorado.

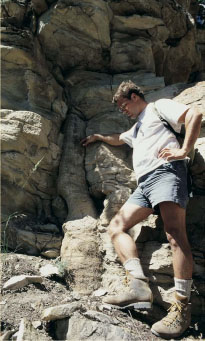

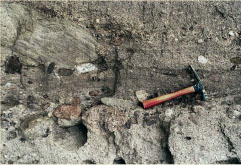

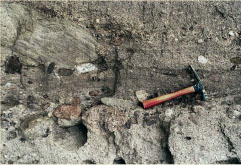

The Fountain Formation contains chunks of granite and quartz, remnants of a lost mountain range.

The bottom layer of the 12,000-foot-thick pile of sedimentary rock beneath Denver is the Fountain Formation. It is a 1,200-foot-thick heap of red sandstone that lies directly on top of much older, tortured melted rocks. Three hundred million years ago, the red sandstone was loose sand in the bottom of riverbeds. Now stone, the sandstone layers rest deep below Denver, but on the upturned basin margin they form the first rampart of flatirons along the Front Range. A close look at the rocks shows two big clues to their origin: (1) the cobbles of quartz and granite; and (2) the fossilized cross sections of ancient river sandbars. These features tell us that lively streams flowed from a place made of granite. Just like the granite cobble-choked streams that flow off the flanks of Pikes Peak today, so too did these ancient streams flow from a mountain made of granite. To the north, east, and west, the Fountain Formation grades into rocks that were formed beneath the sea, showing that part of Colorado was an island in a great inland sea.

Fossils arent very common in the Fountain Formation because coarse red sandstone is abrasive and chemically harsh, so it is somewhat of a challenge, but not impossible, to reconstruct the animals and plants that lived here. At the base of the formation in Colorado Springs, fossil root systems in mudstone are direct evidence of scale trees. All parts of these trees were photosynthetic, so the trees had green trunks and green roots. By following the rocks laterally to fossil-bearing areas in central Colorado, southern Wyoming, and eastern Kansas, we are able to find additional evidence of plants and animals. Plants such as the earliest conifers, strap-leaf conifer cousins, and hugely inflated horsetails are known from the area around Vail and Minturn, Colorado. In eastern Kansas, coastline deposits are full of fossil cockroaches, millipedes, dragonflies, pole forest plants, amphibians, protomammals, and fish.

Roxborough State Park is a place where the Fountain Formation has been tipped up and exposed.

Next page