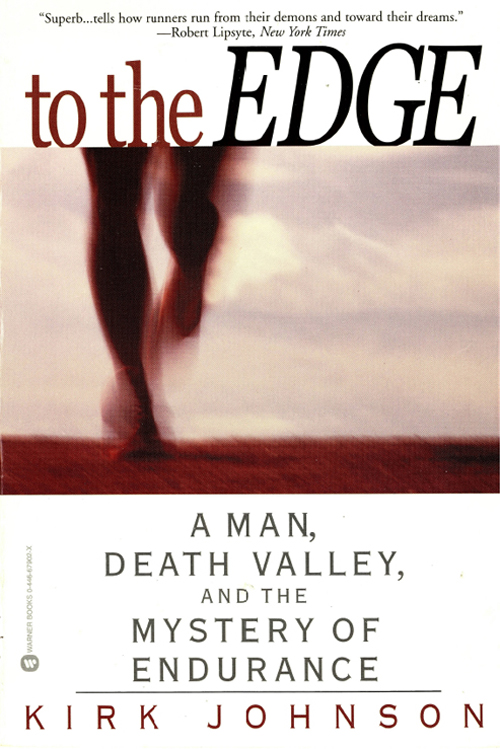

Copyright 2001 by Kirk Johnson

All rights reserved.

Warner Books, Inc.

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: October 2009

ISBN: 978-0-7595-2571-9

ACCLAIM FOR

TO THE EDGE

A splendid adventure, splendidly told, and one more proof that the further you go outside, the further you go inside.

Bill McKibben, author of

The End of Nature and Long Distance

Fascinating lovely passages. Johnson deftly blends excitement, tension, grief, and humor.

Publishers Weekly

A terrific story, beautifully written, which provides yet more proof that the best sportswriting is about events at which the fewest people are present. A wonderful piece of reportage.

Dick Schaap, coauthor of Bo Knows Bo,

Montana, and Instant Replay

Pleasing authenticity.

New York Times Book Review

I marveled at how very, very far Johnson went and I marveled more at how deep. Johnson has returned out of the wilderness with a story so vivid and right and profound that he made me gasp at the real meaning of victory.

Kenny Moore, author of Best Efforts,

former senior writer at Sports Illustrated, costar of Personal Best,

and executive producer and cowriter of Without Limits

Evocative. A nice job: Like all good sports narratives, this is more about meeting challenges than winning titles.

Kirkus Reviews

A thoroughly absorbing book. The narrative gathers momentum, until we are completely riveted by this portrait of one small man struggling to discover himself.

Amby Burfoot, editor of

Runners World and Boston Marathon winner

A superb book.

Rockland Courier-Gazette (ME)

A compelling story of survival and triumph in one of the worlds most grueling physical challenges.

Joshua Piven, coauthor of

The Worst-Case Scenario Survival Handbook

Essential reading for anyone who cares about pushing personal limits thoughtful, emotional, and entertaining.

Martin Dugard, author of

Surviving the Toughest Race on Earth

A reminder of the extraordinary feats even ordinary people are capable of.

Alberto Salazar, former marathon world record

holder and three-time New York Marathon winner

Johnson, by lowering himself into the soul-scouring cauldron that is Death Valley as a journalist, reemerged as a devotee. He used his blood as the ink, and the dedication to his subject drips from every page.

Rich Benyo, editor of Marathon and Beyond

For Gary, who made me run

For Pat and Wayne, who helped me run

And for Fran and the boys, who brought me home

Special thanks to the NetworkAlice and Eri Golembo, Bob and Julia Greifeld, Sharon and Herb Lurie, Rod Granger and Susan Obrechtfor their unflagging if not always comprehending support and encouragement, to my running buddy Jim Colvin for the breadth of his spirit, and to my many friends at the New York Times.

In a dark time, the eye begins to see,

I meet my shadow in the deepening shade;

I hear my echo in the echoing wood

A lord of nature weeping to a tree.

I live between the heron and wren,

Beasts of the hill and serpents of the den.

Whats madness but nobility of soul

At odds with circumstance? The days on fire!

I know the purity of pure despair,

My shadow pinned against a sweating wall

That place among the rocksis it a cave,

Or winding path? The edge is what I have

Theodore Roethke, In a Dark Time

The reasoned argument is but a surface exhibition. Instinct leads, intelligence does but follow.

WILLIAM JAMES,

The Varieties of Religious Experience

A t 4:30 A.M. on a Sunday in mid-June 1999, I was sitting on the shoulder of a two-lane road near Ellerbe, North Carolina, flat-assed on the blacktop, legs stretched out in front of me, staring into the dark woods that pressed up to the lip of the pavement. I was beaten and about as alone as Ive ever been in my life.

I was trying to tell myself that what had happened was a good thing. I should get acquainted with the bottom. I should touch the walls of it and think of it as a learning experience, because I would surely be back, in circumstances worse than this. I turned off my flashlight and let the night swallow up the bubble of illumination in which Id been running. In the predawn stillness, even the birds and frogs that had been keeping me company clammed up.

It didnt work. As much as I tried to tell myself that what I was experiencing was somehow edifyinga landmark on the road Id begun six months earlierthe truth is that I was scared to death. Id gone, by that point, about 43 miles in an oddball footrace called the Bethel Hill Moonlight Boogie, a 50-mile ultramarathon that loops all night long around the towns of Rockingham and Ellerbe near the South Carolina border.

Forty-three miles! The number clanged and clattered in my head as I sat there. Forty-three miles! Only a few months earlier, it would have been an unimaginable achievement for mea distance beyond the furthest margins of belief. But that night I could only see it as a crushing defeat and a portent of failures to come. I felt exposed for the fraud that I wasan imposter and a pretender. Id gotten into something that was far, far beyond me.

Who am I kidding? I called into the darkness, though there was no one to hear. Who am I kidding?

Up until that year of my life, Id been a runner and athlete of the most casual and modest sort. I seldom ran much farther than five miles, never participated in races and had no real goals except fitness and the flush of well-being that I felt from exercise. I came from a nonsportsor even, you might say, anti-sportsbackground. One of the most humiliating images from my childhood was a photograph of my Cub Scout troop, taken behind our house by the big old black walnut tree that dominated the yard. Every other boy was up in the branchesclowning, grinning and hanging upside down in his silly blue uniformexcept me. I lived there and I couldnt climb my own damn tree. I was the chubby little failure left to stand and smile bravely but pitifully beside my mom, the troops den mother.

By high school, Id slimmed down physically, but in my head I was still the angry, frustrated fat boy. Id also become a self-cast radical, tilting against whatever injustice I thought I saw, and my schools sports program loomed as the perfect target. In its hierarchy of brawn over brain, I saw a celebration of mediocrity. In the rah-rah cheering of school spirit, I perceived a cynical calculation by administrators seeking to control the student body by manipulating our emotions. And in the barriers to participation, I felt the sting of a biased reward system that favored children of the pampered middle class over working-class types like me who had to get part-time jobs after school. Underneath all that rage I was just jealous. Athletics was for others and therefore it sucked.

I carried pieces of that hoary old critique inside me for years, rattling around like spare parts. Every time I read about some prima donna professional sports star sulking over his plush contract, the old revulsion would flare up. But in the summer of 1997, it all began to crumble. An ambush of odd and unexpected changes in my life, especially the sudden and shattering death of my oldest brother, Gary, triggered a need somewhere inside me that I hadnt even known I had. By the time of my crisis that morning in North Carolina, Id becomethough I still couldnt quite say the word aloudan athlete in a way I never would have imagined possible. I was exactly one month away from attempting what many veteran runners consider the most extreme footrace on earth135 miles across Death Valley, California, in the middle of the summer. Id entered a race called Badwater.