Table of Contents

Guide

Table of Contents

To Ashley and Sage

Badwater Basin, Day 1

Introduction

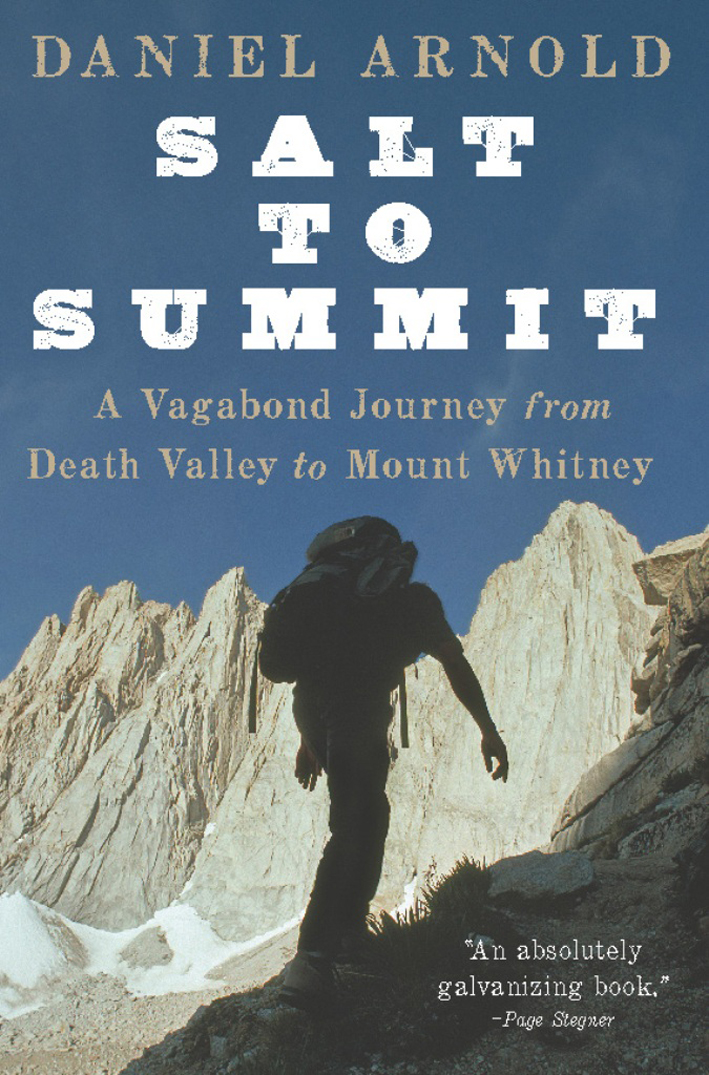

CLIMB YOUR MOUNTAIN FROM THE BOTTOM

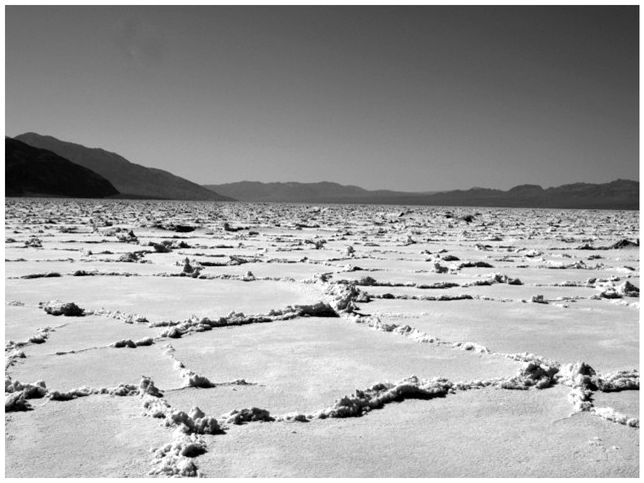

Badwater Basin, the sink in the center of Death Valley, is 282 feet below sea level. It is a vast salt pan, the lowest and hottest place in the Western Hemisphere. Getting pinched between the salt and the sun there feels like hanging out in a jerking oven. Its the apocalypse as written by a banana slug.

Due west and a little north, Mount Whitney rises 14,505 feet above sea level. The top edge of the granite crest that cuts California lengthwise into western farm valleys and eastern deserts, its summit is the highest point in the contiguous United States. The upper mountain, a 2,000-foot-high arrowhead of bare granite and snow, points straight up. The blue-gray stone looks unreal from down in the orange and brown below. Eighty air miles separates the summit from the salt.

It wasnt long after I began climbing mountains as a teenager that I first heard of this convergence of mountain and desert. I remember thinking, this must be the perfect way to climb a mountain. Start at the very bottom, and end at the very top. What more could a mountaineer want? The first person to whom I ever mentioned the idea was a graying, wooly-bearded geology professor who had spent some time in the desert. He looked at me in a fatherly way and said something like, If you think the Sierra is badass, just wait till youre in the desert ranges. Which I took to mean, Kid, you wont even get far enough to get yourself into trouble. In the desert, that isnt very far at all.

So I spent years wandering around Death Valley, climbing its canyons and peaks, crossing its dunes and salt flats. The Big Project continued to rattle around in the back of my mind. I came to know Death Valley well and to appreciate the land separating the salt and the mountain as more than just the distance in between. This is the most rugged part of the basin and range, where the peaks and troughs crest highest and dip lowest. The land has personality: reticent, unforgiving, but also a bewitching storyteller when you listen to it, full of magic and beauty and tragedy. I began to see the salt and the summit as the ornaments on either side of the central character: the desert.

The juxtaposition of Badwater and Whitney was noticed in gold rush times, as soon as the first surveyors began to circulate the freakish elevations they had calculated. Josiah Whitney, the geologist enshrined by name on the mountain, gloated enthusiastically over the geographic wonders of California. Newspapers across the border in Nevada criticized the surveying work done, though their complaints focused more on the immodesty of one state claiming both the highest and the lowest points in the country for itself. Years later, when the road connecting Badwater with the Owens Valley was completed, John Crowley, a Catholic priest and booster of all things Eastern Californian, organized an elaborate ceremony involving wagons, cars, an Indian runner, and an airplane relaying a gourd of snowmelt down to the brine at Badwater. Norman Clyde, famous Sierra mountaineer, also took notice of the desert and claimed an odd kind of speed record for himself by starting a stopwatch atop Mount Whitney, racing down the eleven-mile Whitney Trail, jumping into a friends car at Whitney Portal, and driving to the dunes at Stovepipe Wells in just over seven hours. Now, each July, the Badwater Ultramarathon is run in the opposite direction, and the cars carry only the gallons of Cytomax and kilos of food consumed by the runners along the way.

The thread of asphalt linking Badwater Basin to Mount Whitney is the fastest way to get from one to the other. Its also the least interesting. The road avoids entire mountain ranges and dodges immense canyons. By its very nature, it smooths over the jagged edges of the landthe exact edges I most wanted to get under my skin. I wanted to cross the desert mountains and crawl through the bottom of those canyons, so I planned a different route.

Roads and trails were out. I would avoid anything designed to make travel easy or fast. And I would go at a time of year when the desert would burn and the mountain would freeze. I chose April, hoping for triple-digit temperatures at Badwater and deep snow on Whitney. I wanted to be hot, to be cold, to rub my nose in the largest uninterrupted wildness I could find. I expected the crossing to take two or three weeks. In that time, I imagined, Id pass through all four seasons. This is the story of a journey through extremes, walking across land that magnifies heat, climbing wind-haunted mountains, wandering canyons where geologic time is laid bare.

Though I traveled alone and off-trail, I had the company of an eccentric group of local ghosts. Long before air-conditioning blunted the summer and fast cars offered instant escape, a handful of inspired lunatics tried to make this country home. This place is undeniably hostile to life, and yet it worked powerfully on the imaginations of certain dreamers, vagabonds, and misfits. More than a story of passing through, this is also a story of trying to stay, of people drawn to the harshest landscape in the American West and held here when the desert got into their blood.

Out in the arid country, the land speaks. Voices leak from the dunes and mining camps, the creosotes and mountains. The more I listen, the more I want to hear. Beware the sun and wide-open distances, guard your water and your sanity, lose yourself in the rocks and canyons, and youll find the words in the silence.

Chapter 1

HITCHHIKING IS CARBON NEUTRAL

All told, I have had little travel in my life which has yielded so much profit on the exertion as the old Mojave stage. I understand that the road is well furnished now with gas stations and hot-dog stands, and the trip can be made in a few hours without incident. Which seems on the whole a pity.

Mary Hunter Austin, Earth Horizon, 1932

I began on the corner of Torrance Boulevard and the Pacific Coast Highway, a convergence of a dozen lanes heavy with midday traffic. I had grown out my beard as sunblock. My pants were old favorites, stitched and patched and faded to the color of the desert itself. I carried a gigantic backpack stuffed with empty two-liter soda bottles that I would fill with water when I reached Furnace Creek. The driver of the Torrance 3 let me on without a second glanceI was not the strangest thing floating around the Los Angeles County mass-transit system. The bus bumped us all along past strip malls and concrete. At the corner of Torrance and Hawthorne, as I waited for a second bus, a kid with a skateboard and baggy corduroy shorts looked me up and down. Been traveling long? he asked, at last. I should have said yes or all my life, but instead I tried to explain that I lived just down the road. Uh-huh, he said. He seemed dubious but willing to believe that I might be speaking in some kind of interesting code.