Table of Contents

Guide

Table of Contents

To Ashley

INTRODUCTION

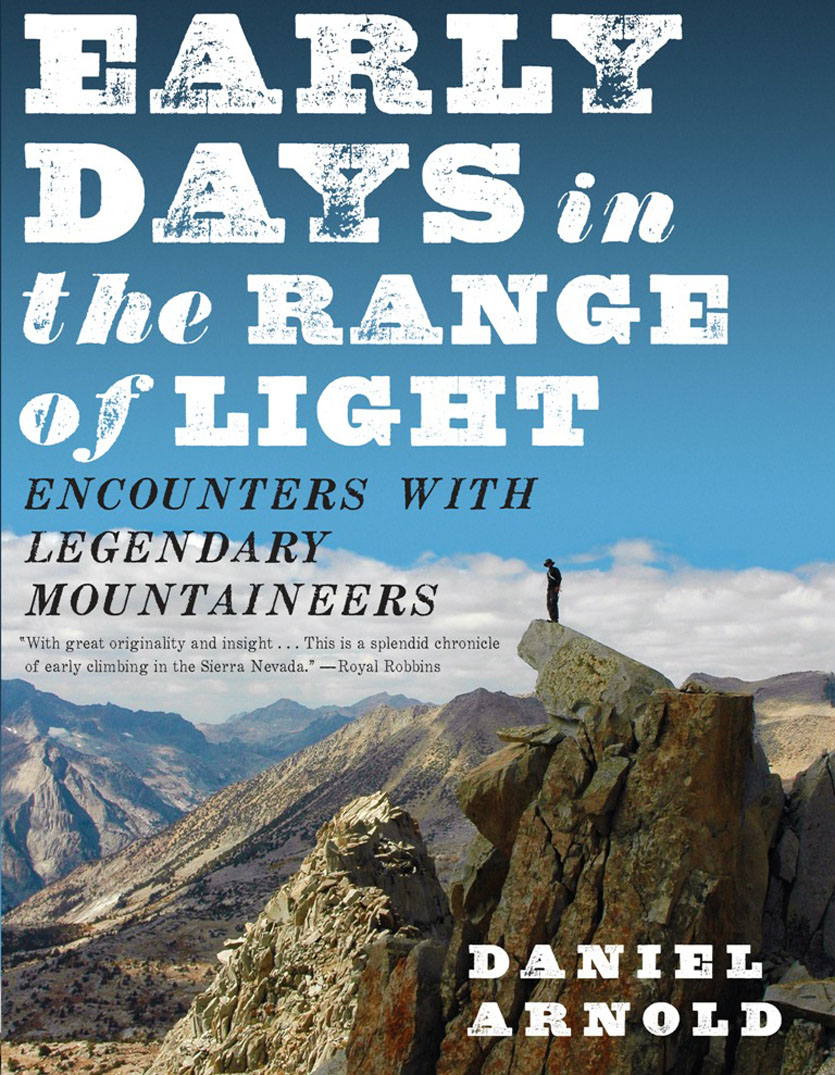

The Range of Light

IN THE SUMMER of 1931, a handful of the strongest and most experienced mountaineers in California gathered at Garnet Lake, near Mount Ritter, a place where deep blue pools reflect the splintered outlines of craggy black peaks. They had come to explore and climb the mountains of the Ritter Range, and to learn something new about the calling they shared.

The Californians had a visitor from the East, and it was his presence, and the knowledge he brought with him, that distinguished the occasion. Robert Underhill, a professor at Harvard and a member of the Harvard Mountaineering Club, had been invited by one of the Californians, Francis Farquhar. The two men had met the previous summer on an expedition to the Canadian Rockies during which Underhill taught Farquhar rope techniques that had not yet spread to the western half of North America.

Climbers in the Sierra Nevada had occasionally used ropes, but only to lasso projecting horns of rock, or for a follower to use as a hand-line through a difficult spot. At the Underhill Camp, as it has since been called, they learned how to tie themselves into the rope and to catch a falling climber. Before, a fall on a serious route could only end in catastrophe. Now, so long as the rope held, a falling climber had a second chance.

The Underhill Camp brought California into the modern age of climbing. Even today with vastly improved equipment, the rope systems employed by climbers from Joshua Tree to Yosemite to Castle Crags can all be traced back to the basic methods taught at Garnet Lake in the summer of 1931.

But the camp also ended a grand, too-often forgotten chapter of the mountaineering story. Men and women had been climbing the peaks of the Sierra Nevada for nearly seventy years before Underhill set foot in California. This early lot of mountaineers had no ropes or pitons or special training. They had only their fingers, their boots, and an immoderate excess of boldness. What climbers now call free-soloing was simply standard practice then. They traveled the high places without the physical and psychological armor which we now haul into the backcountry to shield ourselves from the elements and from the mountains hard indifference to our soft bodies.

Seventy years saw many faces come and go in the high peaks: geologists, artists, historians, conservationists. Some took jobs simply to be close to the mountains: a coolheaded postman stationed in Yosemite, the cantankerous principal of the Independence High School. A few of the early mountaineers, like John Muir and Clarence King, have become part of the mythic West. Others, like Norman Clyde, are prominent only within the realm of climbing history, while the adventures of Charles Michael and James Hutchinson have been largely forgotten even by climbers.

These early climbers and their stories work a kind of gravitational magic on me, pulling me into their world. It is the directness of their approach to the mountains that I find so appealing. Lacking outdoor schools and climbing walls, no one taught Muir or Michael the right way to climb. They learned their lessons straight from the mountains; from the rocks, glaciers, and storms. Since they had no equipment they paid more attention to the world around them than to the objects they carried. Muir often traveled alone through the Sierra with little more than a notebook, a knife, and a pocketful of bread crusts. On their honeymoon in 1896, Bolton and Lucy Brown hiked across the width of the Sierra to climb a new route on Mount Williamson, and Bolton estimated that with their provisions for four days, his pack weighed twelve pounds and Lucys weighed three. The fast-and-light mentality sweeping through todays outdoors community would be entirely familiar to the first generation of mountaineers.

Innovations in climbing gear beginning with Underhills ropes and mutating toward the nylon and aluminum barrage of the modern gear store have allowed climbers, including myself, to visit some of the most dramatic places on earth. I have loved being high up El Capitan and Half Dome, looking wide-eyed across Yosemite; there is nothing equal to the sensation of being a microbe riding a granite wave. But I do not love the equipment that takes me there. Staring at a mess of carabiners, cams, and pitons makes me feel like a technician in a laboratory; spending days in a harness gives me the feeling of being leashed.

Over the past decade I have traveled slowly back in time. I spend more and more of each summer wandering the mountains and less time dangling from ropes. And I spend my city time in libraries reading the accounts of the early days on the thick pages of old copies of the Sierra Club Bulletin, and on the sheets and scraps of journals and letters. The stories I have encountered are gripping for their moments of physical courage and their stunning descriptions of the Sierra landscape. Probably the greatest pleasure for me has been to learn the ancestors reasons for venturing into the mountains in the first place. From Browns pursuit of the untainted wilds of his boyhood fantasies to Muirs search for a new God to replace his fathers, they struggled to explain the impulses that drove them to high summits, to answer that unanswerable Why? that follows mountaineers up every climb.

Somewhere along the way, I decided to tell the history of this time, and it seemed most appropriate to tell it through the individual stories of mountains and mountaineers. I began to assemble a list of peaks that best represented the spirit of the era. All would have to be high and visually strikingpeaks climbers would lose sleep over in the nights before an attempt and look back on afterward with pride. There could be no easy route to their summits. Many peaks in the Sierra have steep, dramatic faces on one side, but easy hiking on another. The peaks I chose are climbers mountains, accessible only via difficult terrain from all directions.

With a list of peaks in hand, I returned to the libraries. I wanted the most adventurous climbs made by the most headstrong climbers, so I read the report of each mountains first ascent. The best of these episodes is what you will find here: fifteen of the most difficult and notable routes along with the stories of the men who climbed them. The climbs cover the Sierra from north to south and from 1864 to 1931. Because the peaks were all difficult and coveted, the first climbers to reach their summits tended to be the most active and accomplished mountaineers of the era.

The library was my winter refuge, when snow ruled the high country and the days held more dark than light. For the past four years, in the summers, I have followed the climbing ancestors, physically retracing their routes up the mountains. I realized that in order to tell their stories, I had to climb the way they did, so I left my modern climbing paraphernalia at home. When I climbed their routes I carried no ropes, no harness, no climbing shoes. When the footsteps I followed were lightest, as with Muir, I left my sleeping bag and backpack behind, too, and spent days living out of a small canvas sack slung over my shoulder. With the nylon and aluminum advantages removed, the playing field tilted back in the mountains favor, and several of these climbs tested both my ability and good sense.