Copyright 2022 by Meg Hafdahl & Kelly Florence

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

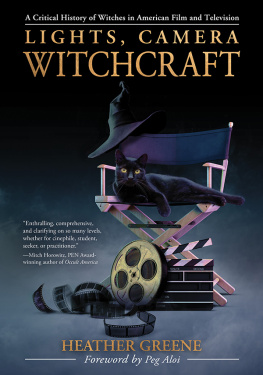

Cover design by David Ter-Avanesyan

Cover images by Shutterstock

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-6718-8

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-6719-5

Printed in the United States of America

We dedicate this book to the witches of the past, present, and future who used their powers for good.

C ONTENTS

I NTRODUCTION

Double, double toil and trouble;

Fire burn and caldron bubble.

Fillet of a fenny snake,

In the caldron boil and bake;

Eye of newt and toe of frog,

Wool of bat and tongue of dog,

Adders fork and blind-worms sting,

Lizards leg and howlets wing,

For a charm of powerful trouble,

Like a hell-broth boil and bubble.

William Shakespeare

Shakespeares words are timeless. While they were written on parchment hundreds of years ago, they still resonate today. This Song of the Witches from Macbeth is no different, casting an indelible spell on our understanding of the secret life of witches. The classic media depiction of witches dressed in black, circling a cauldron bubbling with animal parts has endured in everything from goofy cartoons to terrifying horror films. Over time, the story of the witch has come alive in a million different forms: good, bad, spiritual, demonic, cannibalistic, healing, young, and old. In this book, we aim to pull back the veil of stereotypes and reveal the true history, legends, and science that inhabit the mystical world of witches.

Now, kiddies, follow along if you dare! (Meg and Kelly cackle and disappear in a plume of smoke.)

SECTION ONE

T HE O RIGINS

C HAPTER O NE

T HE W IZARD OF O Z

Say the word witch and chances are youll conjure up an image of a woman wearing a pointy black hat (cackling maniacally, of course). The word itself has taken on many iterations over the centuries. The first mention of witches in the Hebrew Bible appears in the first book of Samuel (28:325), which refers to a story about a woman performing necromancy and magic. Writers in the fifteenth century used the term maleficus , meaning a person who performed harmful acts of sorcery against others.

The earliest known written magical incantations come from ancient Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), dated to between the 5th and 4th centuries BCE.

Witches have come a long way on screen from The Maid of Salem (1937) to Wandavision (2021). Perhaps the most famous portrayal is the Wicked Witch from The Wizard of Oz (1939). Ill get you, my pretty, and your little dog too! This iconic line, spoken by the Wicked Witch of the West (Margaret Hamilton) in the film, epitomizes the witch villain. She has a horrific green face, cackles wildly, and is not only willing to hurt a young girl but her lovable pooch too! How could we possibly empathize with this terrible, monstrous woman? We can and do through the journey that is the musical Wicked (2003). Created by Stephen Schwartz and Winnie Holzman, Wicked is the story of Elphaba and Galinda (later Glinda), witches in the Land of Oz.

The journey from page to stage took many iterations over the course of one hundred years. The original book, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum, is considered the first American fairy tale. Baum, who wrote fourteen novels in the Oz series, was inspired by places and people from his childhood, including a recurring nightmare in which he was chased across a field by a scarecrow. What is the psychology behind this? Parents who fear the inclusion of witchcraft in their childrens stories often believe that by reading these stories their kids will turn to the occult and begin practicing spells themselves. Experts say thats not how reading works, though. This was demonstrated in a study by psychologists Amie Senland and Elizabeth Vozzola:

During the medieval times of Britain, scarecrows originated as young children who would throw stones when birds landed in fields. When the Great Plague killed nearly half of Britains population in 1348, they switched to scarecrows being made out of stuffed sacks of straw.

In their study comparing the perceptions of fundamentalist and liberal Christian readers of Harry Potter , Senland and Vozzola reveal that different reading responses are possible in even relatively homogeneous groups. On the one hand, despite adults fears to the contrary, few children in either group believed that the magic practiced in Harry Potter could be replicated in real life. On the other, the children disagreed about a number of things, including whether or not Dumbledores bending of the rules for Harry made Dumbledore harder to respect. Senland and Vozzolas study joins a body of scholarship that indicates that children perform complex negotiations as they read. Childrens reading experiences are informed by both their unique personal histories and their cultural contexts. In other words, theres no normal way to read Harry Potter or any other book, for that matter.

Scarecrows began in the fields of ancient Greece as wooden statues carved to represent Priapus, a Greek god of fertility.

The Wizard of Oz came out in 1939 and is considered one of the American Film Institutes (AFIs) one hundred greatest American movies of all time. Judy Garland, grew up not far from where I did. We often visited her home in Grand Rapids, Minnesota, as it has been turned into a museum. Many kids I knew liked the movie but were terrified of the wicked witch. How did Margaret Hamilton come to portray her character?

Hamilton was an actress who gained credits in local theatre and several films before she auditioned to be the Wicked Witch of the West. Some people in the industry told her to get a nose job if she ever expected to be cast. She didnt, though, and got over what other people thought of her looks. That confidence no doubt carried over into her audition and she got the part. Hamilton never missed a chance to help children see the witchs human side. Having been a kindergarten teacher, she understood children and knew it was important to let them know the witch wasnt real. She spoke to Fred Rogers on Mister Rogers Neighborhood (19682001) and said about her character, shes very unhappy because she never gets what she wants, Mr. Rogers. Most of us get something... but as far as we know, that witch has never got what she wanted.

What medical conditions could explain the witchs green skin? A condition called hypochromic anemia was historically known as green sickness for the distinct skin color sometimes present in patients. Other symptoms from this type of anemia include lack of energy, shortness of breath, headaches, and low appetite. Its caused by a lack of vitamin B6, certain infections, or diseases. Other conditions that have been known to cause green skin include multiple organ failure, contact with copper, or the use of certain drugs.

Next page