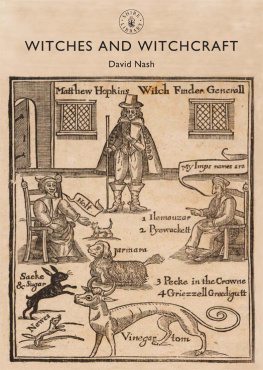

WITCHES AND WITCHCRAFT

David Nash

Der Hexenmeister, seventeenth-century painting by Domenicus van Wijnen. It contains many elements popularly believed to be associated with witchcraft: warlocks, wands, familiars and monstrous animals.

A Charge of Witchcraft by Henry Gillard Glindoni (18521913).

CONTENTS

A Spanish witch flies to the sabbat on the back of a horned cloven-footed demon. Witchcraft in Spain was the subject of systematic war conducted by the Inquisition who, unlike their undeserved reputation, maintained sensible legal procedures, used torture very reluctantly and may have thus prevented witch-hunts in the area from getting out of hand the way they did further north.

INTRODUCTION AND PRE-HISTORY

T HE SUBJECT of witchcraft and witches endlessly intrigues every succeeding generation. As each age becomes more psychologically and technically sophisticated our interest in the reality and sometimes alien nature of witchcraft remains remarkably undiminished. It is tempting to view this interest as a hangover from the past and romanticism about a more primitive form of existence when mankind was somehow closer to nature.

As such, this apparently remote episode often fascinates because it involves beliefs and behaviour patterns that seem very obviously different to those of our modern and considered world. So why do we persist in wanting to study and understand what happened to these people (believers, witches and victims) and why? While it often seems a distant self-contained period of history that exerts a quirky hold over the imagination, strangely it is also familiar because some of its elements have important resonances with modern experience. The hunting and punishment of witches was very often a form of scapegoating individuals blamed for the misfortunes of other individuals or of whole communities. We have our modern counterparts in the outbreaks of hatred towards bankers, foreigners and sex criminals and what they are believed to have done. We are also encouraged to understand such feelings through our creation of stereotypes of evil, ranging from Freddie Kruger to serial killers like Fred West or Ted Bundy. It could also be said that a taste for the supernatural has become considerably more in fashion since the 1990s than it had been for some time previously. The gothic dark style is in vogue with heavy metal music witnessing something of a renaissance, while childrens literature is full of references to magic, from the writings of Philip Pullman to the ultimately popular expression of this in J. K. Rowlings Harry Potter series.

Some social commentators also suggest Western society is experiencing a process of re-enchantment a distrust of wholly rational explanations of the world and universe which has reawakened interest in more magical outlooks. This leaves rational explanations of the world to become only one potential choice amongst many where they once claimed to rule. After all, the proportion of Americans who believe the lunar landing in 1969 was hoaxed in a warehouse rather than believe it really happened continues to grow. Evidence that our environment is turning against us as it did during the period of the early modern witch-hunt is all around. We are increasingly more attuned to environmental catastrophe and the marginal nature of existence in the Third World and areas that could flood as a result of global warming. Likewise, some economic and social prophets talk of the world being one bad harvest away from chaos and the collapse of financial markets has re-introduced the First World spectacularly to a reality of uncertainty, risk and irrationality. Just as numerous economic, social and cultural strains in the early modern period made people believe in irrational powers, so today, our faith in the benevolence of science is now weakened. There is distrust around issues in cloning, the fear of the consequence of genetically modified food life again seems full of the drip, drip, drip of risk, mundane and serious dangers.

The Witch by Albrecht Drer, depicting a witch riding backwards on a goat, accompanied by four putti (winged male children), c. 1500.

Witches casting a spell to bring rain. Woodcut from Ulrich Molitors De Laniis et phitonicis mulieribus, Constance, 1489.

However, the phenomenon of witchcraft is more correctly seen as an issue not so much of spells and past irrational modes of behaviour, but of the exercise of power. This particular factor can be seen everywhere in witchcrafts past and in its present. Theologians in the early modern period (c. 14001700) believed power had been dispensed to the Devil and those who sought to follow him. These same theologians also believed that they had a solemn duty to wield their own power to combat and destroy these people and thus preserve Christendom from its enemies. Some twentieth-century commentators were pressed into asking whether individuals themselves actually really believed they were in league with the Devil and were actually witches or whether those persecuted for the crime of witchcraft were actually unfortunate victims of societys fears and spontaneous actions. Again the issue of power is evident since, while we cannot be certain what people believed, it is extremely likely that many who found themselves powerless within a rigid and inflexible society may have, in their mind, wanted to make such an agreement. In their own psyche and consciousness a pact with the Devil made them powerful and answered many of their concerns. The importance of power is also evident in the demise of witchcraft, as alternative explanations for events in the natural and human worlds became more sophisticated and powerful than witch beliefs.

In the early modern period witchcraft was prevalent in northern, southern and central Europe France, Germany, Switzerland extending north to Norway, Sweden and Finland, east to Russia and across the western seaboard to America and the Spanish territories of the new world. As such it was a universal phenomenon, common to all cultures. Witch-hunting in the early modern world was an episode more or less confined to a three-hundred-year period between 1450 and 1750. This was an age of considerable upheaval, during which the whole fabric of civilisation changed. Population levels fell as a result of constraints upon the physical environment. Agriculture became less productive, possibly caused by a sustained alteration in the physical climate as demonstrated in tree-ring data which has led some historians to suggest that Europe experienced a mini ice age. As a further result of these catastrophes the economies of Europe and America suffered a severe downturn. The dislocation caused by the squabbles of the Reformation and the religious wars that ensued augmented these troubles.