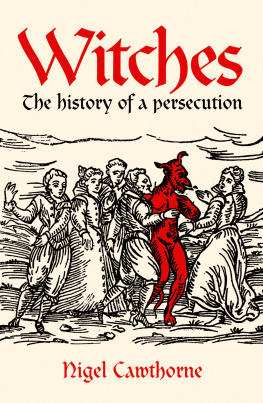

Harry Potter is in the ascendant and Wicca is one of the fastest-growing religions in the world today; in the twenty-first century witches and witchcraft still have us under a timeless magical spell. Harry Potters phenomenal success owes much to author J.K. Rowlings masterful ability to bring to life some powerful archetypal figures. The witch, the wizard, the magician; we all intuitively know who they are and what they can do. Transformers, shape-shifters, healers, soothsayers, challengers, destroyers; every culture has its witches and wizards and in every culture they are both admired and feared. Young Harry Potter and his school friends neatly sum up the Western fairytale vision of the witch and the wizard. They fly on broomsticks, wear pointy hats, cast spells with magic wands, brew up potions in cauldrons, refer to dusty grimoires of magical instruction, and keep toads and owls as helpful familiars. To board the Hogwarts Express is to leave reality far behind and to enter a world of fairytale dreamscapes and collective imagining, in which good and evil become a question of black and white and no one stops to ask how witches and wizards came to possess their awesome supernatural abilities.

Back in the real world, however, it is just such questions of good and evil, of natural and supernatural, which have long been at the core of our perceptions of witchcraft, and have shaped the role of witches and witchcraft in our society, often with deadly consequences. This Brief History looks at the relationship between the witch and society in European history. It is time-bound, geography-bound, and, most importantly, reality-bound. It does not deal with fairytale witchcraft, modern pagan witchcraft or witchcraft in non-European cultures. That said, to avoid misunderstanding and confusion, we should perhaps stop for a moment and define exactly what we mean by historical witchcraft and, in particular, how it differs from the modern pagan religion of Wicca. There have been many misconceptions amongst modern pagan witches about the origins of their faith and its relationship to the witchcraft of history. Recently, the scholar Ronald Hutton, in his book The Triumph of the Moon, has undertaken the first professional historical analysis of the birth of what he calls the only religion England has ever given the world, and Wicca has finally been given a firm historical foundation on which to rest, one based on sound academic principles and not on half-truths and romantic myth.

Perhaps the easiest way to approach the confusion and discrepancies that exist between modern pagan witchcraft and historical witchcraft is to look at the subject in terms of the two classical systems of thought that underpin each type of witchcraft. Whilst the magical element of Wicca is ultimately a child (or at least a great-great-great-great-grandchild) of the Neo-Platonic Renaissance, historical witchcraft beliefs had their foundations in medieval Aristotelian thought. The Aristotelian scholars of the Middle Ages believed that magic could only be performed with the aid of demons, hence the accusation that all witchcraft was the work of the Devil. The Renaissance thinkers, however, postulated that magic was a natural science and that absolutely no demons were necessary in order for humans to relate magically to their environment. Whilst Neo-Platonism posited a natural explanation for magic, Aristotelianism posited a supernatural explanation.

The Neo-Platonic system of thought became the dominant one amongst occultists who, since the Renaissance, have largely viewed the practice of magic in Neo-Platonic terms as an entirely natural phenomenon. In modern Wicca this Neo-Platonic occult philosophy of Natural Magic has found a bedfellow in the pantheistic pagan spirituality born out of the eighteenth-century Romantic movement. Wicca has given structure to a religious impulse that animates and imbues the whole of the natural world with a vital life force that moves in cycles of both generation and destruction and permeates and connects every living being. Gods, goddesses, faeries and spirits are viewed either as personifications of this holistic life force or as non-material entities arising from nature. There is no particular concept of good and evil, and man-made evils are generally seen as the result of alienation from nature and the life force that sustains it.

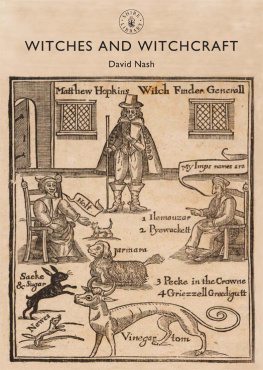

This witchcraft is a whole world (and system of thought) away from the witchcraft that began to take shape under the dominant Aristotelian worldview of the Christian Middle Ages and eventually settled into its classic stereotypical form towards the end of the fifteenth century. It is this view of witchcraft with which we will concern ourselves throughout the rest of this book. In this view, the witch was believed to make a pact with the Devil, whom she worshipped at nocturnal gatherings known as the Sabbat (or Sabbath), which usually took place in some wild and remote area or cave. She flew to the Sabbat with her fellow witches, usually on a broomstick, and there they paid homage to the Devil, whom they worshipped. They invoked demons, cooked up gruesome feasts consisting largely of the flesh of unbaptised babies, and then extinguished the lights and copulated indiscriminately with whomever was closest to hand. The Devil himself, or one of his lesser demons, presided over these Sabbats, and he usually appeared in the form of a man described as being black or dressed in black. At other times he appeared in the form of a goat, a dog, a cat, a toad, or some other animal. The Devil baptised his witches with a special identifying mark, known as the Devils Mark, and they served him by committing various acts of maleficia, malicious and harmful sorcery, which usually took the form of bewitching their neighbours cattle or children, blasting crops, and causing illness and death in their local communities. The witches gained their magical abilities from the Devil and were often aided in their destructive work by demons, who frequently took the form of familiars, or magical pets.

Whilst the ideological foundations for this witchcraft lie in the Middle Ages, it was not a medieval invention. It occurs both before and after the medieval era. Belief in witchcraft can be traced back into antiquity and the widespread persecution of witches popularly known as the Witch Craze did not get under way in earnest until the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Most of us are familiar with the so-called Burning Times, in which those accused of witchcraft were tortured and burnt at the stake. The seemingly epidemic proportions of these executions has led to the term craze being applied to these outbreaks of witch-hunting, which appear to the modern observer to have been the result of some form of mass hysteria. To a large extent, the Witch Craze was a Western European phenomenon and witchcraft developed very differently in Western Europe than it did in Britain and the peripheral regions of Europe. In fact, the main force of the Witch Craze was concentrated within a relatively small central band of Western Europe encompassing France and Germany. The historian Robert Thurston has observed that one could draw a circle with a 300-mile radius around Strasbourg that would encompass well over 50 per cent of all witch trials.

Historians have long sought to explain why the Witch Craze took place when and where it did. It is a phenomenon peculiar to a particular moment in European history, yet the belief in witchcraft was nothing new, and certainly not limited to Europe. The historical study of witchcraft has focused primarily on piecing together the many elements of European witch beliefs that ultimately combined to cause the deaths of an estimated 40,000 people for the alleged crime of witchcraft during the Witch Craze. Many functional theories have been put forward to try to explain the Witch Craze, from social, economic and religious strife to the oppression of women and the need to find scapegoats on whom to blame misfortunes and natural disasters. While all these theories have a valid role to play in understanding the many factors that contributed to both the rise of witch-hunting in general and individual witch-hunts in particular, none of them satisfactorily explains the entire phenomenon. There is no one size fits all theory that adequately covers the history of European witchcraft. Modern historians have concentrated on examining the relationships between the many cultural, religious and legal strands that gradually accumulated and evolved throughout the Middle Ages and into the early modern period and that created the unique set of conditions which allowed the Witch Craze to find form. Both the classic stereotype of the witch that developed on the Continent and the Devil she was alleged to serve were composite figures drawn from a number of different ideological and cultural sources, and fed by a variety of changes in the legal and social make-up of European society over a number of centuries. The belief in witchcraft did not fully exist in its classic, stereotypical form until the end of the fifteenth century, and it is to the preceding centuries that historians must look in order to unearth the origins of the witch beliefs that laid the foundations for the Witch Craze.