O Christian Martyr Who for Truth could die

When all about thee Owned the hideous lie!

The world, redeemed from superstitions sway,

Is breathing freer for thy sake today.

Words written by John Greenleaf Whittier and inscribed on a monument marking the grave of Rebecca Nurse, one of the condemned witches of Salem.

Introduction

T here have been numerous attempts to explain the witch-hunting mania that swept the western world in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Why was it that suddenly people saw witches flying on broomsticks and dancing naked at sabbats with the devil? According to one theory, a grain fungus spread across Europe, which worked like a psychedelic drug, giving hallucinations to those who consumed it. A similar theory has also been advanced for the sudden collapse of the early English colony on Roanoke Island.

Others see it as a product of sexual hysteria. Many of the witchcraft cases in this book have a strong sexual element, often involving young women in the throes of puberty, as in many poltergeist cases.

Was the witch hunt part of a misogynist agenda, a giant conspiracy among men to persecute women? Or was witch-hunting thinly disguised anti-Semitism? Were attention-seeking children the cause? There are sometimes hints of what we now call paedophilia. Could this be the explanation? Or was it all of the above?

But any of these explanations would be wrong. They all see the events of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries though twenty-first century eyes. The cases I have related in this book can only really be understood in their own terms. True, many people confessed to being witches and named others under unspeakable torture. Yet others confessed voluntarily, even though they knew that their confession would result in a horrible death. While some people plainly made accusations for material gain, others had unimpeachable motives.

Some said that they had seen things and done things that, in our eyes, are clearly impossible. Plainly old women do not fly on broomsticks; the devil does not penetrate thick prison walls to make love to unwilling victims. People do not turn into wolves. But many good, honest and sincere people reported such things and they were believed.

Imagine what it was like to live in a society where everyone believed in witchcraft. Imagine living in a society where, even if you had not seen people flying or dancing naked at sabbats, everyone believed that such things went on. Both the witch-burner and the witch and often one became the other had the same mindset. They believed that Satan was present on the earth, and that his purpose was to corrupt good Christian people by any means necessary. If one had, lets say, a dream with an explicit sexual content, it would be easy to interpret it as the work of the devil. Surely, if you are a good, upright and sexually continent person, such ideas in your mind must be the work of the devil? It is not hard to see some of the confessions as what is now known in child sexual abuse cases as false memory syndrome. If the sexual abuse of a child by its parents has disturbing effects in later life, then if you are a disturbed adult, it is not hard to believe that your parents must have abused you and that you have blocked this unpleasant fact from your mind. Then, with a little creative therapy, it is possible to fill in the ghastly details.

Likewise if all sin proceeds from the devil then, if you are sinful as we are told we all are then you mst be in league with him. Surely Satan could have visited you one night, whisked you off to a sabbat, then forced you to forget about it? In that case how can you trust your own memory? After all, those who are trying to obtain a confession from you are trying to save your immortal soul. Might it be that the allegations they are making are right?

The collective madness we see in these witch-crazes also has echoes in events that are closer to our own time. In the witch-burning in Germany, there are disturbing harbingers of the Jewish holocaust.

And such frenzies can even occur in the most liberal of societies. In 1950s America, there were the aptly named witch hunts where Senator Joe McCarthy and other leading politicians in Washington sought out Communists and fellow travellers in the movie industry and other walks of life. Many innocent people were imprisoned, and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg paid with their lives.

It is not difficult to understand how America could be gripped by an anti-Communist fever in those post-war years. Throughout the twentieth century, Communists had been vehemently opposed to the rampant capitalism of the United States, and Russia was a long-term enemy. In the wake of the First World War, the Soviet Union had taken over half of Europe. Then in 1949, China, the most populous country on earth, became Communist, and Communists were also on the march in Korea, Vietnam, Laos, Malaya and, closer to home, in Cuba. The Soviet Union had also recently developed its own atomic bomb and had missiles that could deliver enough explosive power to wipe out an American city. For the first time since the war of 1812, mainland America was under threat.

The playwright Arthur Miller made the comparison between the McCarthyite witch hunts and the Salem witch-craze in his play The Crucible. He showed how a society could turn in on itself in the face of a pervasive external threat. New England society in the late seventeenth century was beset by fears of attack by Native Americans and the French, and there was also the ever-present fear of disease, crop failure and economic hardship.

By and large, the witch-crazes in Europe sprung up at times when countries were beset by religious wars. France and Germany, particularly, were torn apart by armed struggle between Catholics and Protestants. Cities and whole regions would change their religious affiliation overnight, sometimes more than once. In the face of such uncertainty, a collective madness sets in. We now live in such uncertain times.

I have presented the cases in this book using court reports, depositions, letters, confessions, torture records and other written material from the time. I have reported the evidence without comment so that the reader can make up his or her own mind how such things can happen. Any attempt on my part to explain these cases in twenty-first-century terms would risk explaining them away. In some cases, the victim faced a terrible dilemma: either confess and be burnt to death or stay silent and die horribly under torture. One can only hope that the victims found their religion a comfort in such extremis. But others freely confessed to flying, turning into wolves or other animals or making love to the devil himself. Their evidence cannot merely be discounted because, rationally, such things do not happen in the real world. Their real world was different from ours. It is worthwhile remembering that many things we believe now will look just as absurd in three or four centuries time.

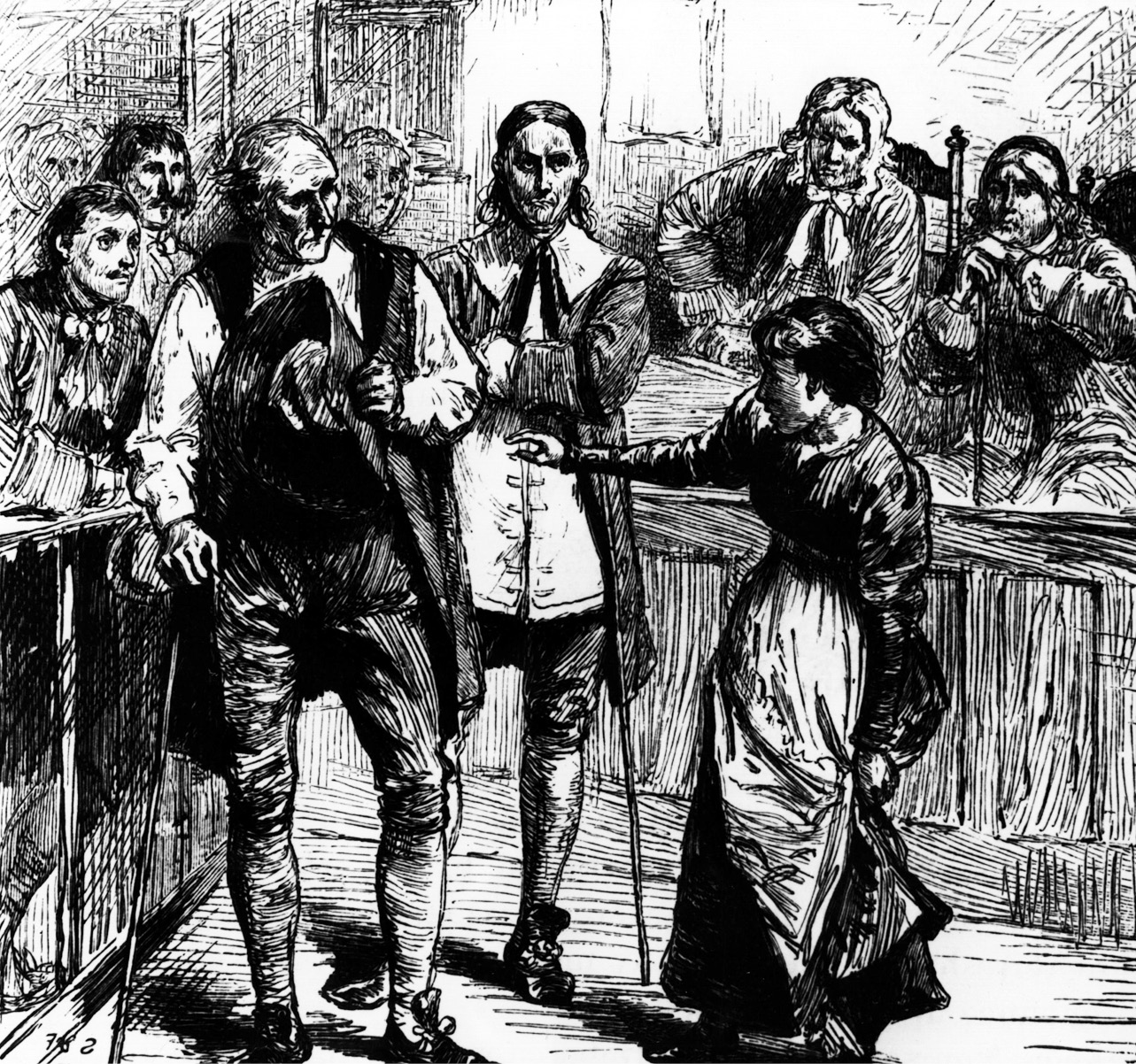

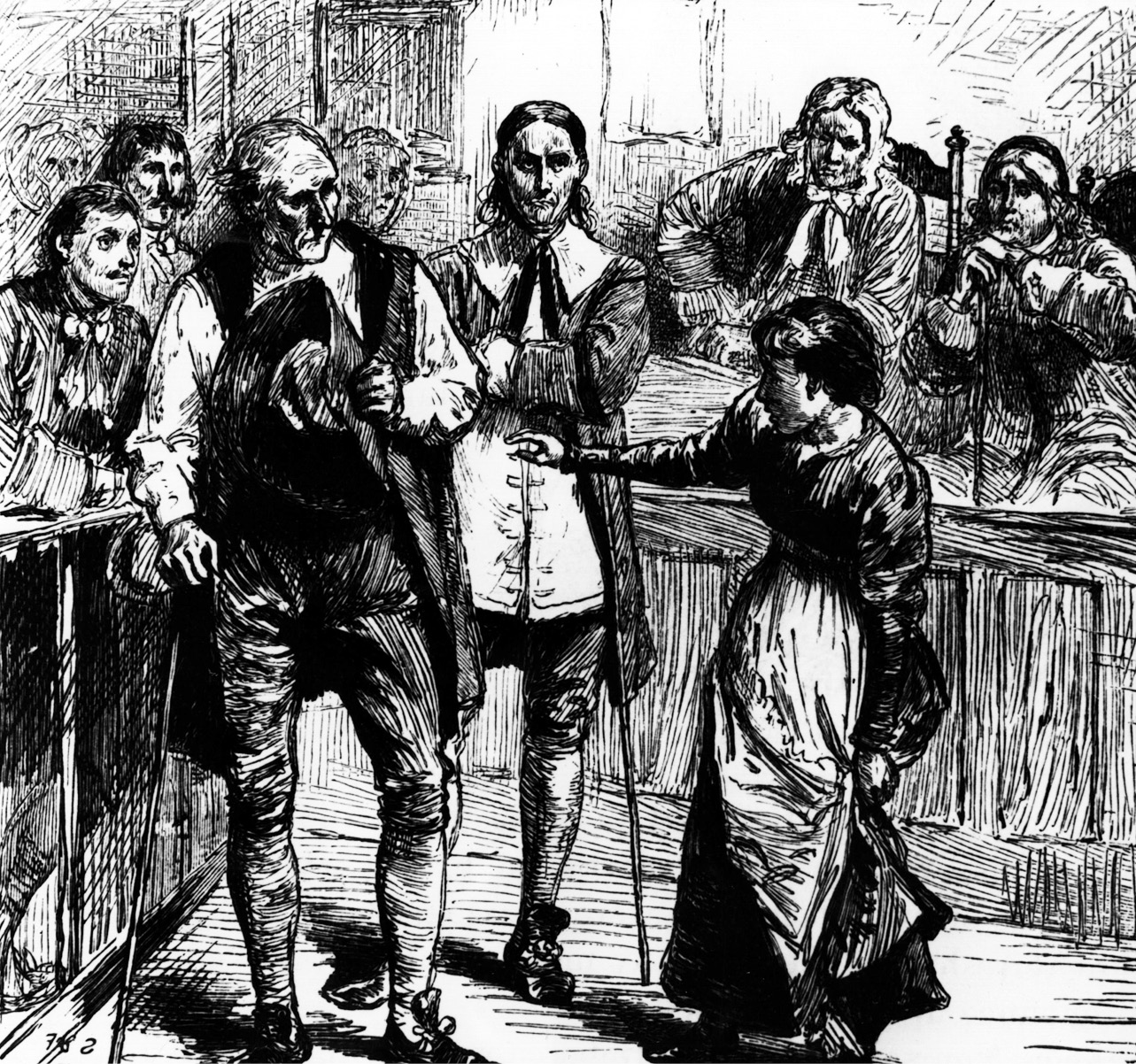

Giles Corey confronts his accusers at his trial for witchcraft in Salem, 1692. Eighty-two-year-old Corey refused to plead, and was pressed to death as a result.

1

The Crucible

T he devil was abroad in New England in 1692. The colonial powers England and France were at war. The Indians were on the warpath. Pirates were hindering trade. Smallpox was raging. The winter was cruel and taxes were crippling. To the Puritans of New England, such a litany of misfortune could only be the work of the devil and his agents on Earth witches.

The witch problem came to light when a group of young girls gathered in the house of the Reverend Samuel Parris in Salem village to listen to the West Indian tales of the slave woman Tituba. Two of them, the Reverends 9-year-old daughter Elizabeth and her 11-year-old cousin Abigail Williams, got so excited that they suffered fits of sobbing and convulsions, and Elizabeth threw a Bible across the room. This was not the first time that the two girls had drawn attention to themselves, both being known as somewhat wilful and headstrong: it would, however, gain them more attention than they had perhaps bargained for.

Next page