First published in 1976

This edition first published in 2011

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

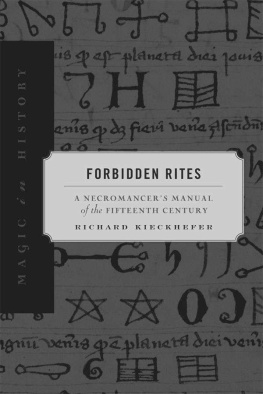

1976 Richard Kieckhefer

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or

utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now

known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any

information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the

publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered

trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent

to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 13: 978-0-415-61927-1 (Set)

eISBN 13: 978-0-203-81784-1 (Set)

ISBN 13: 978-0-415-61925-7 (Volume 5)

eISBN 13: 978-0-203-82833-5 (Volume 5)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but

points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would

welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

European

Witch Trials

Their Foundations in

Popular and Learned

Culture, 13001500

Richard Kieckhefer

First published in 1976

by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd

76 Carter Lane,

London EC4V 5EL and

Reading Road

Henley-on-Thames

Oxon. RG9 I EN

Set in Monotype Ehrhardt

and printed in Great Britain by

Western Printing Services Ltd, Bristol

Copyright Richard Kieckhefer 1976

No part of this book may be reproduced in

any form without permission from the

publisher, except for the quotation of brief

passages in criticism

ISBN 0 7100 8314

Preface

The topic of witchcraft has enjoyed popularity for some time, both among scholars and with the broader reading public. It has aroused numerous controversies, and the positions taken in these debates have been diverse. One might pardonably ask whether there is reason for still further work on such well-tilled soil. Clearly my answer would be affirmative. I have profited greatly from the research of many scholars, and made use of their material and analyses; I can hardly presume to supersede their treatment of the subject entirely. If there is any justification for my turning to late medieval witch trials anew, it is the need for methodologically rigorous study of the evidence. The methods used in this work, though neither technical nor revolutionary, are in some measure distinctive. The application of these methods results in a picture of the topic which is revisionist both in general outline and in many details. If the revisions gain acceptance, or even if they provoke discussion, I shall be gratified to have contributed toward knowledge of this important subject.

The scope of this work, as sketched in the Introduction, is admittedly broad: I have endeavored to cover most of western Europe, for a period of two centuries. A study of some specific locality might have better claim to being complete and definitive. Yet the purpose of this work is to ascertain what effects the proposed methodology will have on the total picture of late medieval witchcraft; the patterns produced by a local study would in this regard be of little consequence, since there are so few extant documents from any given region. I have made every effort to take into account all relevant trials cited in modern literature on witchcraft, plus some cases that have been missed in this literature. I have undoubtedly overlooked some records, and there are surely further manuscripts that await systematic investigation in European (and especially English) libraries and archives. One may reasonably conjecture, however, that the broad patterns revealed in presently known materials will not be seriously disrupted by later discoveries. It is theoretically conceivable that unexpected masses of documents will come to light, but given the generally fragmentary character of records from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries it is unlikely that future discoveries will greatly outweigh materials now at hand.

Even if it could claim to be definitive, a work of this breadth suffers a further handicap: when one draws upon records of widely distant regions, the commonalities in the witch beliefs stand out more clearly than the local variations. I have tried to point out regional particularities when they are clearly significant; for example, the reader will encounter contrasts between Swiss and Italian ideas of witchcraft. For various reasons, however, there would be little purpose in making these discrepancies the object of sustained inquiry. In the first place, information from many regions is so meagre that it would be impossible to discuss the topography of witch beliefs with confidence. Second, even if one could isolate distinctive features of regional tradition, any explanation for these variations would in most cases be merely hypothetical, because the social context has been studied unevenly and for many regions insufficiently. It appears, for example, that Swiss traditions were distinctive in many ways. Yet Switzerland is precisely one of the areas for which least social history has been written in recent years, and until the nature of Swiss society has been studied more carefully it would be futile to speculate about the reasons for specifically Swiss popular beliefs.

If this work is general in its geographical and chronological scope, the thematic focus is quite specific. As the title indicates, this is not a comprehensive investigation of late medieval witchcraft, but specifically an examination of the witch trials. Witchcraft literature and legislation are of only peripheral relevance. For these topics Joseph Hansens Zauberwahn, Inquisition und Hexenprozess is still worth consulting, as is Jeffrey Russells Witchcraft in the Middle Ages . I have nothing new to add on these subjects; prolonged discussion of them would merely be a distraction. The subtitle further circumscribes the topic of this work: Certain aspects of the witch trials, such as judicial procedures and political context, receive only tangential consideration here. Emphasis lies on the one central problem, the distinction between popular and learned notions of witchcraft, as these are revealed in the trials. I have treated the content of popular witch beliefs in detail. Because the substance of learned tradition has already been discussed at length in analyses of the witch treatises, and because the learned notions found in the trials are fundamentally the same as those in this literature, I have given them less attention.