Forbidden

Rites

Magic in History

Forbidden

Rites

A Necromancers Manual of

the Fifteenth Century

Richard Kieckhefer

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS

University Park, Pennsylvania

Copyright 1997 Richard Kieckhefer

Published in 1998 in the United States of America and Canada by The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, PA 16802

First published in 1997 in the United Kingdom by Sutton Publishing Limited

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kieckhefer, Richard.

Forbidden rites : a necromancer's manual of the fifteenth century / Richard Kieckhefer.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-271-01750-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 0-271-01751-1 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. Manuscript. Clm 849. 2 MagicHistory. 3. DemonologyHistory. I. Title.

BF1593.K525 1997

Fifth printing, 2012

It is the policy of The Pennsylvania State University Press to use acid-free paper for the first printing of all clothbound books. Publications on uncoated stock satisfy minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Contents

M

Clm 849

I

P

D

C

T

Tables

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek for providing a microfilm and photographs of Clm 849; to the British Library and Cambridge University Library for providing relevant materials; to Martina Stratmann for supplying a codicological analysis of Clm 849; to Barbara Newman, H.C. Erik Midelfort, Steve Muhlberger, John Leland and Frank Klaassen for reading my analysis, sharing with me their insights, giving me the benefit of their suggestions, and helping to protect me from errors; to Charles Burnett in particular, who read both the analysis and the edition of the manuscript with meticulous care and expertise and helped resolve many problems; to Vincent Cornell and Sani Umar for information about Arabic texts; and to Persephone, a familiar companion who reminds me constantly about the significance of my work.

Cave! terrentia hac in scientia latent, si cupis

scire occulta, pericula multa pro te et upupis!

Introduction: Magical Books

and Magical Rites

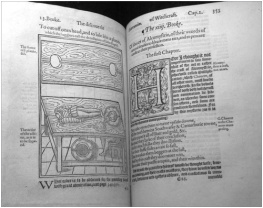

W e are what we read and the power of books to transform the minds and personalities of their readers can give cause for anxiety as well as for celebration. A cluster of related developments in late medieval Europe brought heightened concern about what people were reading. The spread of literacy and the rise of a far wider reading public, lay as well as clerical, brought greater demand for written material. The availability of paper, a medium far less costly than parchment, made books more readily accessible than they had previously been, and allowed for more abundant supply of reading matter to feed this demand, even before the invention of printing with movable type. And the emergence of silent reading habits made reading a more private activity. A book of magic which deliberately and expressly invited contact with demons presented all the hazards of reading in their deepest and most pressing form.

Beginning around the early fourteenth century, possession and use of magical writings becomes a recurrent theme in the records of prosecution. When Bernard Dlicieux was accused in 1319 of having used necromancy against the pope, he was cleared of that charge but nevertheless condemned to prison for merely possessing a book of necromancy. When the books were burned, there were those (as we shall see) who heard the voices of demons in the crackling of the flames.

The book-burning might at times be voluntary: according to a fifteenth-century biographer, Gerard Groot studied magic in his youth, and was accused of practising it as well, but when he converted to a life of piety and foreswore the art of necromancy, he consigned his books of magic to the flames. The movement he went on to found, the Devotio Moderna, was one of the most influential forces in the devotional culture of pre-Reformation Europe, a movement of inner piety nurtured by devout reading, manifested in the copying out of pious phrases in personal florilegia, and financially supported by the copying of manuscripts a movement, in short, firmly grounded in the book-culture of late medieval Europe, and initiated with an act of penitential book-burning.

From the early years of Christianity, conversion to Christ had meant, among other things, doing away with books of magic. The scene at Ephesus, as described in the Acts of the Apostles (18:1919:20), perhaps epitomized what happened on a smaller scale elsewhere. When Paul arrived in the town and made converts to the new faith, a number of those who practised magic arts brought their books together and burned them in the sight of all, and they counted the value of them and found it came to fifty thousand pieces of silver. But in an age when books of this sort were held in deep suspicion one could never count on such clemency, as Bernard Dlicieux well knew.

Anything that arouses such deep anxiety is a subject of historical interest, and books of magic hold considerable fascination indeed. To know why books of magic aroused fear we must gain a fuller understanding of what the books themselves were likely to contain. Most of them no doubt have perished in the inquisitors flames, but some eluded detection and have survived. The focus of following chapters in this study is arguably among the most interesting sources we have for the study of medieval magic: a fifteenth-century handbook of explicitly demonic magic, or what contemporaries called necromancy. This compilation is contained in a manuscript in the Bavarian State Library in Munich. To be sure, the text is neither edifying nor profound, nor is it particularly original; in late medieval Europe there were no doubt many compilations equally illustrative of common magical practice, most of them now lost. But among the manuscripts that survive, few are quite as diverse in content, or as full, explicit and candid in their instructions as this work.

Detailed examination of such a compilation may most obviously help us understand the mentality of the necromancers themselves who copied such books, whether for curiosity or for use. But study of this handbook may clarify several other factors in the history of magic, and three in particular. First, examination of a necromancers manual sheds light on the function and cultural significance of a magical book itself. We will know more about the cultural significance of books generally and we will know more fully the range of meanings a book could have when we have grasped the role of this exceptional category of books. Second, the mentality of the necromancers opponents becomes clearer from examination of such a compilation: the views of the Renaissance mages (such as Marsilio Ficino and Johannes Reuchlin) who insisted that they practised a higher and purer form of magic than did these base necromancers, and those of the demonologists ( Heinrich Kramer and his successors) for whom necromancy was a dark filter shading their perception of witchcraft. The reactions of the opponents may be historically more important than the attitudes of the necromancers themselves, because they tell us more about the culture as a whole, but we cannot begin to comprehend these reactions without knowing the realities on which they were based. Third, the rites contained in this compendium illustrate strikingly the links between magical practice and orthodox liturgy. The analogy I will use is that of a tapestry, whose display side implies a reverse side: so too, a society that ascribes a high degree of power to ritual and its users will invite the development of unofficial and transgressive ritual, related in form to its official counterpart, however sharply it may differ in its uses.