I am indebted to a number of people for the kind support and encouragement they gave me during the writing of this book. Wipro Applying Thought In Schools gave the financial grant that made it possible, and I am indeed grateful to Anand Swaminathan and Prakash Iyer. Thanks to Sheema Mookherjee at Harper Collins India who has been patient, cheerful and prompt in dealing with my endless queries during editing, and V. K. Karthika who gave me the exciting green signal.

Thanks to Vernon Hall who first taught me how to understand psychology, how to think about education and which questions are useful to ask. The title of the book is inspired by a quote from the physicist Richard Feynman, who credits his mother with asking him this question when he returned from school. Thanks to Radhika Neelakantan, gifted artist, who became right brain to my left brain. Her illustrations breathe life into the text, and this will be her first-of-many books. Sumana Ramanan, childhood playmate who went out of her way to remember me at the opportune moment. Ahalya Chari who has been a dear, wise friend and guide for almost fifteen years. Venu Narayan whose support I have relied on, often taken for granted, for so long. Devika Narayan who interviewed several teachers on my behalf, and got quite carried away in the process. Venkatesh Onkar and Kirby Huminuik who helped edit parts of the manuscript, and Michael Little who gave the cover idea. Bharathi Pratap, my gifted music teacher, for enriching my life so much. Prof. C. Seshadri who assured me that a book like this would be useful, and started me off with the push I needed.

Usha Aroor, thank you for responding so immediately and generously to the finished work. Your kind appreciation and help has meant the world to me. Arvind Gupta, thank you for being you: energetic, enthusiastic, committed and caring. Just add me to the long list of people who have been inspired by you. Prof. Yash Pal, thank you for your invaluable advice and kind words, coming as they do out of a deep understanding of education in India and a great love of children.

Finally, I would like to thank the following people: my husband Shashidhar for giving me the idea in the first place, making me believe in it, and giving me all the support I needed to complete the project; Shruthi for being the sweetest and most undemanding of children; my parents for appreciating my every little accomplishment in life, and freely supporting my switch from Physics to Psychology twenty-four years ago; my whole big family on both sides, six-month-old to seventy-three-year-old, for their love, encouragement and good company; my CFL family for giving me friendship, and the space and opportunity to work and grow in countless ways; my students who have taught me lessons I could never have learned from a book; and friends and teachers at the Krishnamurti Foundation India whose dedication inspires me.

After completing her PhD in Educational Psychology at Syracuse University, NY and teaching undergraduates for a few years, Kamala V. Mukunda returned to India in 1995 and joined Centre For Learning, a non-formal school in Bangalore exploring the nature of education (www.cfl.in). She discovered that educators and parents were actively curious about educational questions that have traditionally been researched by psychologists. But psychologists rarely wrote for this audience! Their articles were filled with jargon, and as Kamala found, not even textbooks in Educational Psychology could bridge that gap. Thus she began to write short articles summarizing the research in readable language. When these articles were well received, she decided to write a book on psychology for teachers in the Indian context.

Brain, Evolution and Schooling

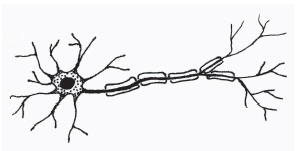

The basics of brain anatomy are learned by most of us in high school. We know that the brain consists of special cells called neurons, that transmit information in the form of electrical impulses. In fact, neurons are distributed throughout the body, to transmit sensations to the brain and commands of various kinds from the brain. But the work of the one hundred billion neurons within the brain represents a fascinating mystery. In ways that we are barely beginning to understand, these neurons give rise to attention, perception, memory, reasoning, intelligence and creativity. Quite a feat!

Structure and Function

Suppose you wanted to understand how some complicated machine works, you might take it apart to closely examine its inner workings. This method works well for clocks, bicycles and carsbut with human brains things are a bit more difficult. When you open the bonnet of a car, you can easily distinguish several different parts inside, even if you are not familiar with their names and functions. When you look at the brain, however, it is harder to see the divisions. At first glance it appears to be a solid mass; closer examination reveals odd shapes and structures that we could call parts.

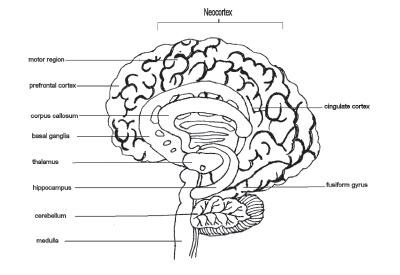

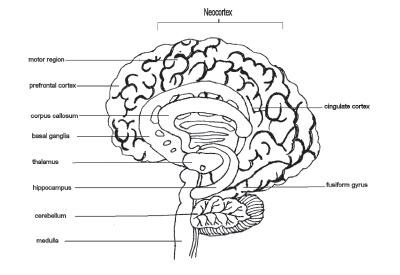

Just as in the car, we would expect that different parts of the brain have different functions, and to a great extent this is true. Some brain parts are older in an evolutionary sense; that is, we share them with most other animals, including reptiles and fish. They have names such as corpus callosum, basal ganglia, medulla and cerebellum. The various functions they serve include reflexes, regulating breathing and heartbeat, coordinating fine and gross movements, regulating sleep cycles and hunger, and much more.

One large section of the brain is its outer covering, called the neocortex. It is a wrinkled, grey mass of tissue, three millimetres thick, and doesnt look very exciting. But this is our so-called higher brain, and it is what sets us apart from the other animals. As teachers, most of the things we want our students to do in schoolunderstanding, remembering, associating, communicating, inferring, problem solving and discoveringare accomplished by the neocortex. In proportion to the size of our body, we humans have the largest brains, and almost all of the increase in size is due to an enlarged neocortex. The figures below present an inner and an outer view of the brain.

One of the ways in which psychologists have learned to draw labelled pictures, such as these, is through the study of patients with brain damage. Brain damage in a patient can be correlated with specific (sometimes bizarre) symptoms. In other words, we can assume that the particular damaged part was responsible for the particular lost or damaged function. Earlier the location of damage could only be known through an autopsy after the patients death, but today brain scanning techniques can give us an instant picture of the damage. In fact, as scanning methods improve, psychologists are even able to look into the normal working brain.

Over more than a century, this kind of research has led to a fairly good understanding of the way functions are divided in the brain. For instance, we all process what we see in the lower back portion of the brain, and we all (with few exceptions) process language in the part of the brain that lies just behind and around our left ear. We all process bodily sensation in a narrow strip across the top of our brain, and send out instructions to our muscles from a parallel strip right in front of that. We all process and lay down new memories with the help of a small structure in the heart of our brain called the hippocampus.

Next page