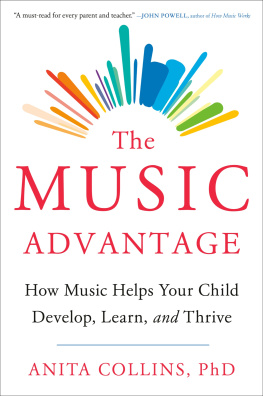

At the end of every academic school year there is some type of celebration: a speech night, presentation assembly or awards ceremony. Whatever it was called at your school or at your own childs school, it probably involved music. It might be a live performance by students or just recorded music selected for the event, but you can bet that at some point during the proceedings there will be music.

As a music teacher, I always marvel at the polar opposite experience of my colleagues and friends in the maths, physical education and English departments around presentation night. They appear to be gently winding down, reports finished and end-of-year decisions made. Meanwhile, music teachers like me are rapidly revving up to the most anticipated, public and possibly judged performance of the year. The entire school community, ready and waiting to be impressed and entertained.

Imagine a mass of musicians from the ages of ten to eighteen in an orchestra in front of the stage, and then me and my other music magic makers sitting facing them. With a running sheet many pages long and every minute of the event scheduled, we are tightly wound and ready for action. After the national anthem is played and the speeches are done, I always breathe a big sigh of relief. The show is rolling and there is a lull as the first awards are presented. If I am honest, it also gets a bit boring, so to keep the adrenalin up I play a game: how many musicians got prizes for subjects other than music this year.

For many years running the answer has been close to the same. Year 7 is announced and ten students are awarded certificates for high achievement in science or English, while some of them receive awards for consistent achievement across all of their subjects. I would get my scorecard out, usually the back of the program, and keep a tally as they walked across the stage. Musician, musician, musician, musician, played trombone for a while but then gave up so that counts, non-musician, musician. Do you want to guess how many on average out of ten I would get in each year group? I present this question to music educators in lectures all the time and they are usually spot onseven or eight of the top ten prize winners either had or were continuing a significant involvement in music.

At that point I could just congratulate myself and my music colleagues on helping to produce the best and brightest in the school, but I often asked myself a different question: did learning music help these students to achieve at the highest levels in their academic work, or were these students already smart to begin with and therefore drawn to learning music? Was it the chicken or the egg, nature or nurture?

Little did I know that these end-of-year musings would take me, a music teacher who had very little interest in science in school and struggled with reading until I was nine years old, into the world of neuroscience and psychology. I have travelled the world looking for answers to these questions, visiting labs working in the field of neuromusical research to understand how music learning impacts on brain development. While I am a teacher of high schoolaged students, I have been amazed at how music listening and music learning at all ages, from day one of life to our final day, has the ability to grow, change and repair our brains.

What I have found out is far more complex than just the chicken/egg or nature/nurture answer. I have learned how babies hear their mothers voice as if it was music, how the necessary neural connections for reading are active when a toddler can keep a steady beat on a drum and how music can remould the brain after injury or trauma. Turns out that the teaching of musicthe chord progressions and performance anxiety and ability to practise effectivelyisnt just content and skills. These parts in fact contribute to growing a human, and suddenly my role in each one of my students lives became so much more important than I ever knew.

But there was no point in just me knowing about this research. It needed to be shared, but it seemed to me that there were a few big hurdles in the way.

First, research is most commonly shared via peer-reviewed articles in academic journals. These articles are often long, hard to read and full of jargon, and the general public would struggle to find them easily.

Second, neuroscientists and psychologists are primarily using music listening and learning to understand how the brain develops and learns, not to understand how to teach music in schools or how to transfer the findings to parents and their children. There is a gaping hole between what is published and what is happening in the world outside the lab.

Third, scientists dont say the word prove. As part of the scientific method, the findings of an experiment will only ever suggest, highlight, point to or explore; one study will rarely if ever prove something definitively. And thats the way it should be. We need to have multiple researchers testing multiple theories in multiple ways multiple times to really understand any phenomenon. Another hurdle is that this research is based on human beings who are all unique and a product of their genetics, personality and experiences. To identify how music and music learning may impact on brain development, researchers need to work with averages and group data, yet every child learns slightly differently and has a different mixture of predispositions and life experiences that have shaped them. For every finding that is reported, there will be an outlier whose experience goes against the norm.

Fourth, research is often incredibly detailed and difficult, and that is why researchers can spend their entire lives pursuing, in one way or another, the complex answer to a simple question. The tricky part in trying to share detailed, expert research with someone who isnt trained in the field, hasnt done research and is trying to apply it to their own experience is the ever-present and pretty much unavoidable danger of oversimplifying.

This book is my attempt, in the face of all of these hurdles, to open the door for you, the everyday reader, parent, teacher and student, to the world of neuromusical research and explain how its findings will in some cases reinforce and in other cases challenge what we think we know about music and music learning. It is just a start, a crack in the door, a shaft of light maybe, but what lies behind the door is a world I have certainly found fascinating, and I hope you will too.

Useful stuff to know before you start

First, some definitions for the purposes of this book. Music listening is just what it sounds like, and our engagement with music can be either passive (background music) or active (music we put on in the car and sing along to). Music education is the more formal learning of music, often through a musical instrument. This might mean any of a combination of weekly lessons, learning in a musical ensemble, reading music and performing throughout the school year and over multiple years. You will see as you read this book that I have opted for the term music learning, and the reason for this is to get us thinking about the many ways music education happens. Music experience can have different meanings at different ages. For young children it looks like play, banging pots and pans with a wooden spoon on the kitchen floor or teacher-led activities that look from the outside like games, and this type of exploration morphs seamlessly into more formal music learning. Music experience for older children includes one-off or short-term learning, such as a visiting ensemble to the school or a four-week drumming immersion program. Music experiences augment music education/learning but are not a substitute for them when it comes to the impacts on cognitive development.

Next page