Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

4035 Park East Court SE, Grand Rapids, Michigan 49546

www.eerdmans.com

2022 Torleif Elgvin

All rights reserved

Published 2022

Printed in the United States of America

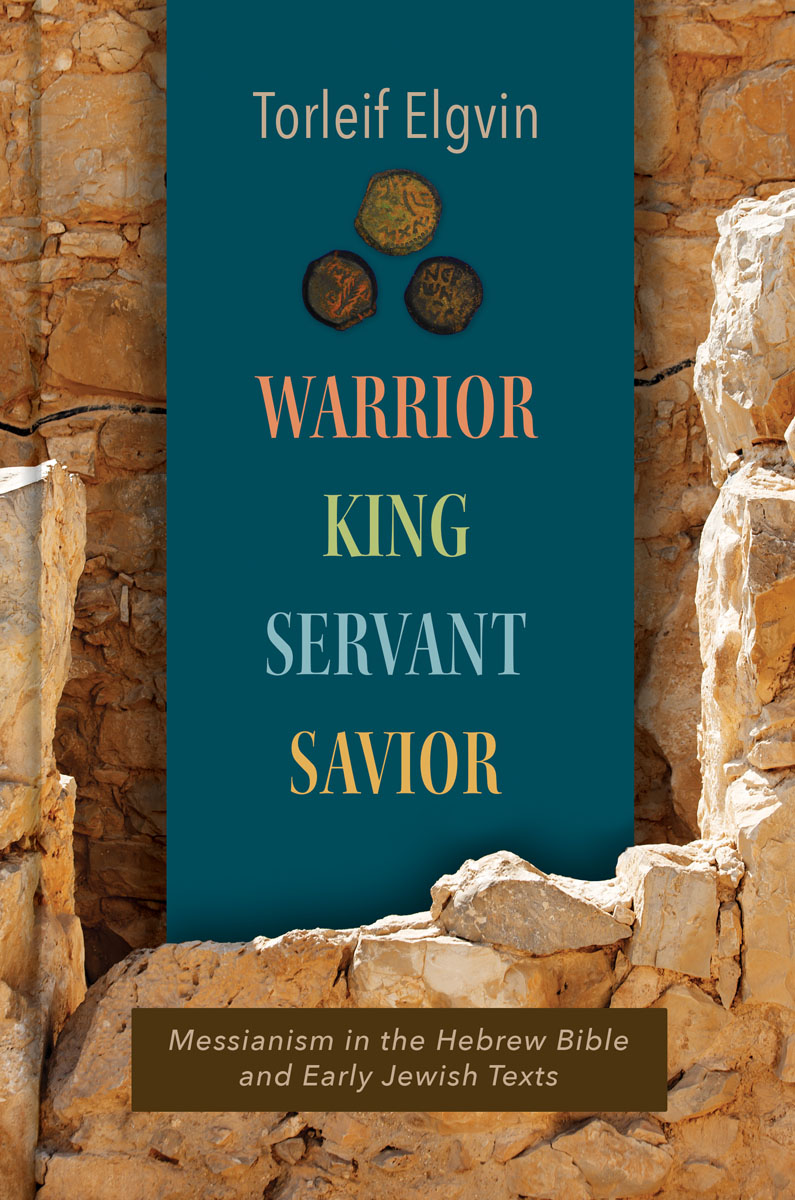

Book design by Leah Luyk

28 27 26 25 24 23 22 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

ISBN 978-0-8028-7818-2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

The publication of this book has received support from NLA University College.

Contents

Preface

In this book I trace the development of royal and Davidic ideology in biblical texts from the tenth to the first century BCE and the development of a multifaceted messianism from the time of the exile onward. In the Bible, messianism and eschatology are interrelated. Thus, my presentation of messianism will be set within the wider hope for the future and the eschaton throughout biblical history. The structure of the book is primarily chronologicalbut at times overruled by thematic considerations.

Messianism in the Hebrew Bible should not be read independently from texts and developments during the second and first centuries. The transmission and procession of biblical texts were dynamic, and the borders of the Ketuvim were fluid until well after the turn of the era. Scholars of the Hebrew Bible need to interact with the pluriform evidence of biblical scrolls from Qumran and the wider Jewish tradition of the Second Temple period. Consequently, in chapters 57 I do not discern between biblical and nonbiblical texts.

I include a final chapter on Jewish messianism in the first millennium after the turn of the era to show how textual lines from biblical and early Jewish texts continue in Jewish tradition. Apart from pointing to some intertextual links, the book does not thematize messianism in the New Testamenta subject well covered in the literature.

Biblical history can be read as history of religion or revelation history. The same goes for the unfolding of Israels messianic hope in this book. I read the Hebrew Bible from the perspective of revelation history, as it was perceived and received by the scribes and editors of the Bible in Second Temple times. For some of us, tracing lines of developments in biblical history may mean trying to see the footsteps of the God of Israel in his interaction with his people through historyavailable to us in texts formatted through the minds and transmitted through the pens of scribes, prophets, Levites, and otherswriters who convey their interpretation of the nations encounter with God. As Durham (1987, xi) says about his traversal of the book of Exodus, to me this traversal of royal, messianic, and eschatological texts is a trip across holy ground. However, readers who prefer to read this book within the paradigm of history of religion or secular history will have no difficulty in doing so.

To a large extent I use literary criticism combined with historical information and archaeological insights to unfold the editorial growth of biblical texts. Identification of stages in the literary growth of a text can reveal changing theological perspectives throughout the editorial processes. It is my hope that readers who identify with a Jewish or Christian faith tradition will not get lost in details of literary criticism but will enjoy seeing how various Israelite scribes through changing historical circumstances gave their specific colors to the pluriform messianic hopes that radiate from the biblical writings.

When it comes to the understanding of prophecy, a theological approach can diverge radically from a secular one. Can a prophet reveal secrets of the human heart or events of the future? Are oracles updated after certain events to fit historical reality? In my perspective, both are possible. The Bible includes vaticinium ex eventu texts, where history is camouflaged as foreseen in prophecy, such as Dan 11. In other cases, a prophetic oracle could be updated after certain events of history had occurred. However, if one encounters the biblical text from a theological or history-of-revelation perspective, one should not exclude that a prophet may be able to foresee events in the futurewhich seems to be a presupposition in much modern secularly influenced scholarship. For Thomas Aquinas, a prophet (in biblical times or in the church) can predict future events or reveal divine insight about the present (Summa Theologica, Part II-II question 172; De Veritate, question 12.3). He connects a prophetic gift with a spiritual sensitivity, a special elevation of the mind. The Holy Spirit moves the mind and thought of the prophet so that he understands, speaks, and acts accordingly.

Sweeney (1996, 22) notes that a prophetic oracle is based on a revelatory experience or vision; it is analytical in character, and it is spoken in response to a particular situation in human events. Thus, prophetic oracles should be interpreted in light of their sociopolitical context in history. The meaning of an oracle should make sense for the prophet and, in most cases, also for his listeners or close to contemporary readers.

To come as close as possible to the sociopolitical context in which the texts developed, this book is in active dialogue with archaeological research relevant for understanding the history of Israel and Judah. I am indebted to Mordechai Aviam, Andrea Berlin, Tali Erickson-Gini, Omer Sergi, Dvir Raviv, Itzhaq Shai, Samuel R. Wolff, and Boaz Zissu for information and feedback on the archaeological evidence. Discussions with Omer Sergi taught me a lot, and Omer generously shared a large number of publications (by himself and others) with me.

This book was finished during the Covid-19 pandemic, when library services were hampered. Therefore, there are relevant scholarly contributions to which I likely should have referred, which I was not able to check.

Biblical translations regularly follow or adapt the NRSV. I also use the 1985 NJPS Tanakh and often provide my own translation. For the Septuagint I mainly follow the New English Translation of the Septuagint (NETS). For translation of the apocrypha I also consult the Jerusalem Bible.

I tried to make the main text not too heavy a read. Particulars in the scholarly discussion are often relegated to the footnotes and in some cases to excursuses.

I would like to express my gratitude to Anders Jrgen Bjrndalen, Hartmut Gese, and Moshe Weinfeld, teachers who set a lasting mark in my study of the Hebrew Bible, and to my teachers in the field of the Dead Sea Scrolls, David Flusser, Geza Vermes, and Emanuel Tov. Thanks are due to Lida Panov, Samuel R. Wolff, and William Schniedewind, who gave me access to prepublication copies of articles; to Michael Langlois for feedback on linguistic and paleographical issues; to David M. Carr, who carefully read through and commented on chapters 15; to Tammy and Reuven Soffer for making the maps; and not least to my copyeditor, David Aiken, and the patient and diligent Eerdmans staff for copyediting and preparing the book for publication.

Figures

Abbreviations

DJD | Discoveries in the Judaean Desert (a series of text editions of Dead Sea Scrolls published by Clarendon Press) |

DtrH | Deuteronomistic History |

G | Septuagint (e.g., GIsa 7:14 means Isa 7:14 in its Greek form) |

Next page