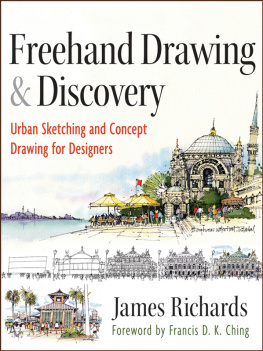

The Still Life

Sketching Bible

David Poxon

Contents

Guide

Foreword

An expanse of clean white paper, a new, sharpened pencil in hand. A momentary excitement, a feeling of expectant anticipation, and then the pencil is lowered and hovers above the surface before finally connecting. Gliding gently at first, pale and wispy marks begin to race with each other and evolve into a glorious trail of granular texture. A twist of the hand makes the marks skip across the paper as a ballerina might pirouette, briefly held in the spotlight. More pressure is applied, then less, and the grip changes from loose to tight, twisting and turning to vary the marks. There is simply nothing like it. Time has no meaning when lost in this process, and all thoughts of worldly matters are abandoned. Filled with hope for the moment, your quest is to capture the joy that you feel in both the drawing process and your subject, and to somehow transfer its essence onto your paper surface.

You are not alone. There are many before you and many more to follow who will make this same thrilling journey. There will certainly be some trials and frustrations, bad days and good, but in the main you will feel uplifted, and there is no excitement to match that of discovering that you have fulfilled your expectations and produced really successful work. I hope that this book, with its carefully planned illustrations and step-by-step demonstrations, will help you set out on the road to becoming an artist, so make time to begin, and take your time to enjoy.

Still life: An historical overview

Since the time of the Ancient Egyptians, art has included what we now know as still lifedrawings and paintings of everyday inanimate objectsand the motivation for such picture making went far beyond that of simply recording worldly possessions. Believing that such objects would be of use to the dead in the afterlife, the artists took great pains to render both food and valued treasures as realistically as they could.

In Classical Greek and Roman art, which included lovely decorative mosaics as well as paintings, still-life art moved into a realm where it could be appreciated by a wide audience, both for its aesthetic qualities and as a marker of the power and wealth of its owner.

More than any other branch of art, the still-life genre has been exploited not merely for its own sake as art, but also as a vehicle to express meanings beyond the main theme of the picture. In the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance period, religious and other symbolic meanings were attached to the inclusion of certain objects in paintings, for example, the transience of life was often depicted in the form of flowers, petals, candles, or skulls.

Still-life art evolved into a highly skillful shop window for the brilliance of the Dutch artists of the 17th century. Paintings of tables adorned with the fruits of the earth became extremely popular, and the reputation of these artists spread across Europe, through France and Spain, and further afield.

Of the Spanish artists perhaps the most widely revered is Diego Velzquez (1599 1660) who included wonderful mini still lifes of simple kitchenware within his paintings known as kitchen pieces.

Two Men at Table

Although not technically a still-life piece, this is one of Velzquezs kitchen pieces in which exquisitely painted still-life objects feature alongside figures. The painting appears perfectly balanced although seemingly divided into two areas. The translucent fruit placed at the jugs neck is an important compositional feature which helps achieve this visual harmony.

Still Life With Bowls of Fruit and Wine-jar

This piece from the Casa di Giulia Felice (House of Julia Felix) dating back to 1st century BC is a typical example of early Roman still life. The Romans made great use of household objects and fruit in their still-life pieces. In the form of paintings and mosaics, their art had a functional, as well as decorative purpose because it often represented the wealth of its owner.

Velzquez was an important influence on the 19th-century French artists Gustave Courbet and Edouard Manet, both of whom painted still lifes as well as many other subjects. Pierre-August Renoir, Paul Czanne, and Vincent Van Gogh took still-life art into a new dimension where objects were shaped by light and color into designs rich with dancing patterns of textural marks. These paintings were very different to the lavish displays of the Dutch school: Manet often painted the remains of his own luncha ham and a loaf of breadwhile Czanne chose fruit and vegetables from his own kitchen and garden. In the 19th to early 20th centuries, the American artist John Frederick Peto created beautiful paintings by combining commonplace objects. Items such as letters, keys, old books, and other trappings of everyday life were interpreted with incredible skill to bring out their subtle textures. Many of Petos subjects emphasized the precision of the underlying drawing, which ensured that his works were fused with an emotive strength.

Sunflowers

This is one of a whole series of sunflower paintings that Van Gogh made during the 1880s. The passion he felt toward his art and mark making is clearly visible in the heavy application and swirls of paint.

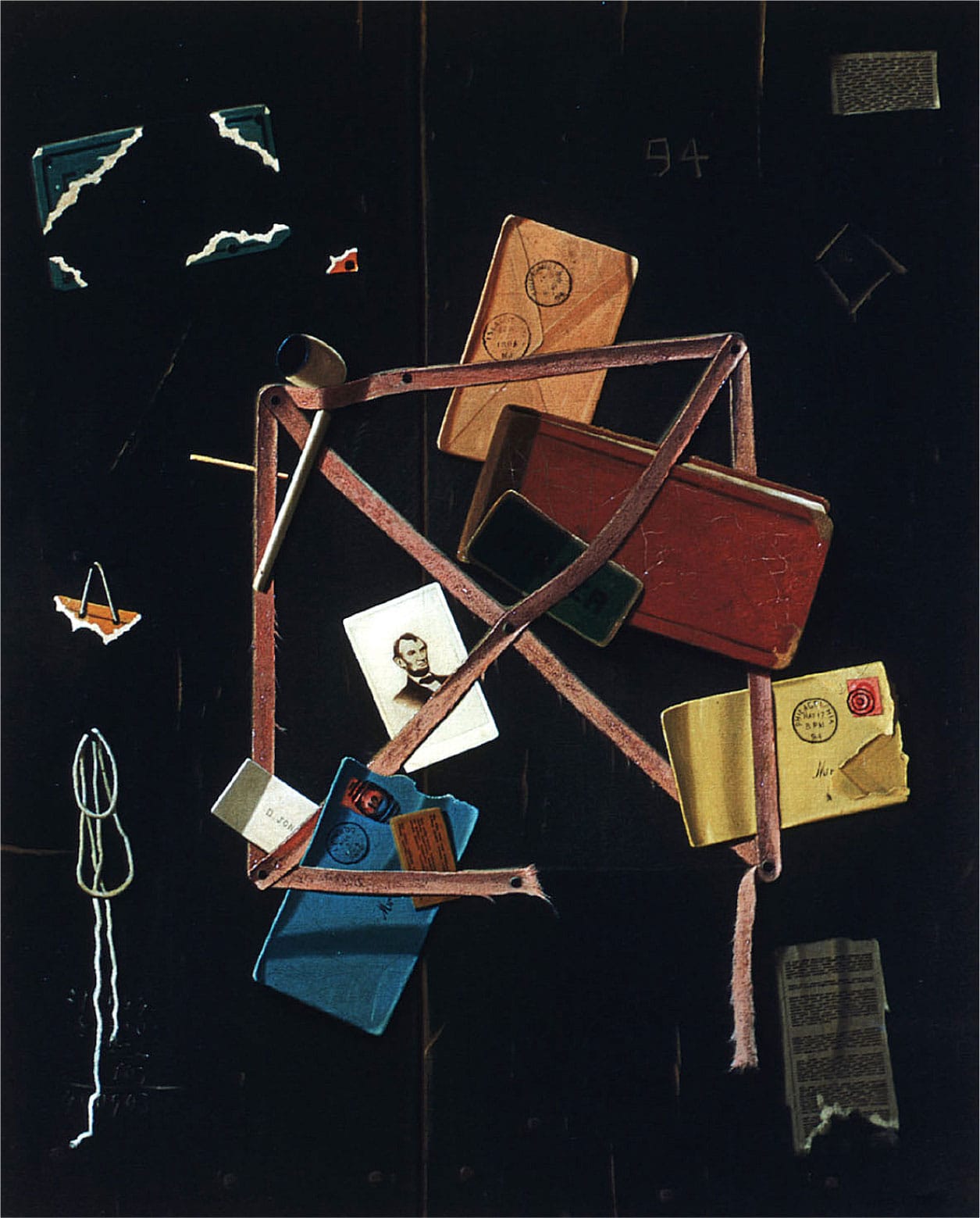

Old-Time Letter Rack

John Frederick Peto, born in 1854, is now regarded as the foremost still-life painter of his period. The above is a piece from the trompe loeil genrea genre of still life that exploits the peculiar nature of human perception to create the illusion of reality of the painted objects. Despite being a master of this genre, Peto was little known in his lifetime. He was completely forgotten after his death in 1907, but was rediscovered in 1947 by a prominent art critic.