About the Author

Steve V. Coxon, Ph.D., is a veteran public school teacher who now serves as assistant professor of gifted education at Maryville University in St. Louis, where he directs the graduate programs in gifted education and the Maryville Summer Science and Robotics Program for High Ability Students. Along with building LEGO DUPLO with his two young children, Steves primary interests are illuminating means by which schools can develop spatial ability, creativity, and other important STEM talents in children and identifying and serving high-ability children from poverty. Visit him on the web at http://stevecoxon.com and follow him on Twitter at @GiftedEdStLouis.

Author Note

Correspondence concerning this book should be addressed to Steve V. Coxon, School of Education, Maryville University, 650 Maryville University Dr., St. Louis, MO 63141. E-mail:

Theory, Definitions, and the History of Spatial Ability

Although Howard Gardner introduced the term spatial ability into popular knowledge in his 1983 book, Frames of Mind, Francis Galton first theorized the construct more than 100 years earlier in 1880 as what he called mental imagery. Galton (1880) defined this as the vividness with which different persons have the faculty of recalling familiar scenes under the form of mental pictures (para. 2). Lohman (1993) suggested that spatial ability has multiple facets, each focused on different aspects of image processing: generation, storage, retrieval, and transformation. Visualization, spatial-visualization, spatial capacities, and spatial intelligence have been terms used by various researchers and theorists as synonymous with spatial ability.

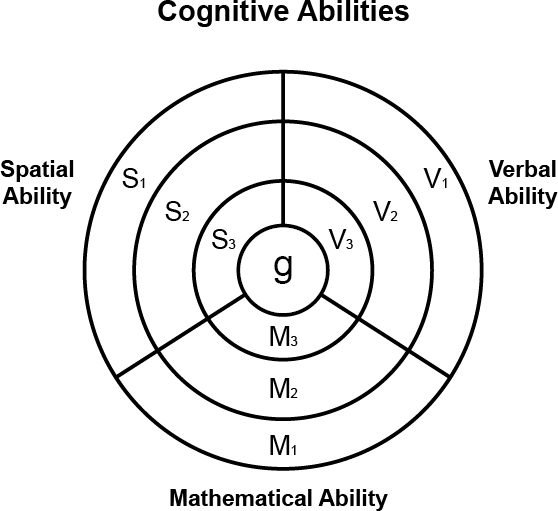

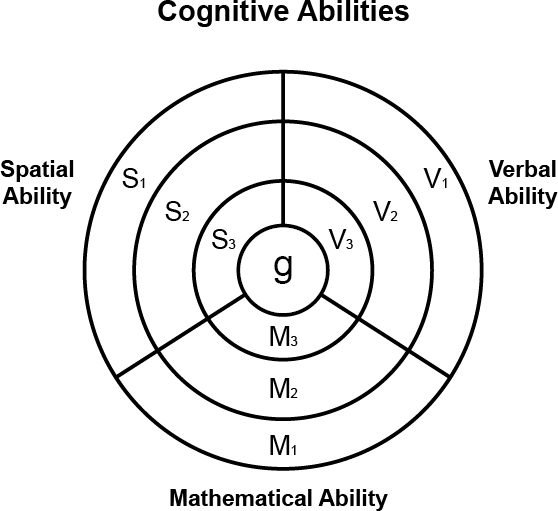

Spatial ability is a factor of intelligence. The Cattell-Horn-Carroll three stratum theory of cognitive abilities has been adapted as a simple radex that displays three abilities that are important to school and life success: spatial, verbal, and mathematical (Wai et al., 2009; see ). The radex centers on g, or general intelligence, the construct measured by intelligence tests that generally report scores on an IQ metric. Assessments of different abilities tend to have a high correlation, usually around .65 (Jensen, 1984). The common factor is g, which represents common processes of the brain, not common items of knowledge, skill, or learned behavior (Jensen, 1984, p. 98). This means that assessment scores are largely explained by test takers g and partly explained by lower order factors like spatial ability as well as learned knowledge and skills.

Radex of cognitive abilities based on Carrolls model. From Spatial Ability for STEM Domains: Aligning Over 50 Years of Cumulative Psychological Knowledge Solidifies Its Importance, by J. Wai, D. Lubinski, and C. P. Benbow, 2009, Journal of Educational Psychology, 101, p. 821. Copyright 2009 by the American Psychological Association. Reprinted with permission.

Although differences in measured spatial ability are in large part explained by g, Jensen (1984) did find that measures of spatial ability increased validity in predicting performance in jobs requiring spatial ability. More recent longitudinal research affirms the predictive validity of spatial assessments (Wai et al., 2009). On spatial assessments, we can assume that we are actually measuring g, innate spatial ability, developed spatial talent, and a small amount of error. When intervention studies demonstrate improvements for research participants on a spatial measure and carefully control for error, we can assume that the improvement is primarily based on an increase in developed spatial talent.

It is a common mistake to assume that spatial ability is somehow equated with mathematical ability or that math courses are also spatial courses. In fact, math and language abilities correlate together very highly at .76, whereas math and spatial abilities correlate at only .61 and verbal and spatial abilities correlate at only .59 (Wai et al., 2009). One can even consider math and verbal abilities to be dichotomous with spatial ability; the former use symbol systems in thinking and expression while the latter is visual. Some math coursework may contain spatial facets, especially geometry, but the focus is in manipulating symbol systems. Likewise, high-ability adolescents who grow up to become teachers as adults tended to have tested with verbal strengths and relative mathematical and spatial weaknesses (Wai et al., 2009).

The importance of spatial ability in STEM fields has long been known. With the launch of Sputnik in 1957, the U.S. had a flurry of interest in both giftedness and STEM education. In their report for the National Science Foundation, Super and Bachrach (1957) emphasized spatial ability as an important characteristic in the development of future STEM contributors. They recommended that longitudinal studies be conducted to better understand the importance of spatial ability and that school programs be created to develop spatial talents. Two longitudinal studies that solidified the importance of spatial ability to STEM success are described in the Review of Key Research section of this book. However, school programming has largely neglected developing spatial ability in students despite the fact that a growing body of research has suggested benefits of such programming for participants (e.g., Coxon, 2012a; Sorby, 2005; Uttal et al., 2012; Verner, 2004). This book seeks to offer teachers, parents, and others who work with pre-K12 students a variety of means by which they can offer spatially-focused education to help improve the flow of talent along the STEM pipeline from our youngest potential innovators through high school to ensure they are prepared and motivated to engage in postsecondary STEM programs.

Characteristics of Spatially-Able Learners

Of gifted adolescents, about half are equally strong in both math/verbal and spatial abilities and another quarter have relative strengths in math/verbal abilities and relative spatial weaknesses (Wai et al., 2009). Both of those groups tend to do better in school and end up with better jobs than the remaining quarter, those with spatial strengths and relative math/verbal weaknesses (Mann, 2006). This is not because the spatially able do not have a wealth of potential to offer society, but because of the traditional focus on math and verbal abilities in schools, testing, and college entrance requirements.

Spatially-able learners tend to be different than their peers similarly gifted in math and verbal domains. Spatial ability is developmental, with facets emerging and strengthening as children age. The spatially able are more often creative (Liben, 2009), more likely to be introverted (Lohman, 1993), more likely to have hobbies (Humphreys, Lubinski, & Yao, 1993), and possibly more likely to have reading disabilities and other verbal difficulties that make it difficult to be successful in traditional classrooms (Lohman, 1994; Mann, 2006). They are also considerably more likely to become engineers, artists, and physical scientists (Flanagan, 1979; Humphreys et al., 1993; Wai et al., 2009). Females are less likely to have high spatial ability, but are more likely to go into fields requiring high spatial ability when they are spatially able (Humphreys et al., 1993).

A word about characteristics is warranted here. These are tendencies, not rules. We can apply them to the group as a whole, but characteristics among individuals will vary. There are spatially-able children who will grow up to be uncreative engineers or extroverted scientists. Some have no hobbies or have hobbies that are not obviously spatial. Plenty are advanced readers. There are females who score at the highest levels on spatial assessments. To believe that a child with spatial ability has all of the characteristics discussed here without knowing him or her personally is stereotyping and must be avoided.

Next page