Open University Press

McGraw-Hill Education

McGraw-Hill House

Shoppenhangers Road

Maidenhead

Berkshire

England

SL6 2QL

email: enquiries@openup.co.uk

world wide web: www.openup.co.uk

and Two Penn Plaza, New York, NY 10121-2289, USA

First published 2011

Copyright Andy Tolmie, Daniel Muijs and Erica McAteer 2011

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence from the Copyright Licensing Agency Limited. Details of such licences (for reprographic reproduction) may be obtained from the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd of Saffron House, 610 Kirby Street, London, EC1N 8TS.

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

ISBN-13: 978-0-33-523377-9 (pb) 978-0-33-523378-6 (hb)

ISBN-10: 0335233775 (pb) 0335233783 (hb)

e-ISBN: 9780335240609

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

CIP data applied for

Typeset and eBook by Graphicraft Limited, Hong Kong

Printed in the UK by Bell and Bain Ltd, Glasgow.

Fictitious names of companies, products, people, characters and/or data that may be used herein (in case studies or in examples) are not intended to represent any real individual, company, product or event.

The Open University Press MediaCentre allows eBook purchasers to access digital resources that accompany the printed book. Visit www.openup.co.uk/mediacentre

Contents

Professor Andy Tolmie, Psychology and Human Development, Institute of Education, University of London, has a background in developmental psychology and more than 20 years experience of teaching statistics to psychology undergraduates and postgraduates.

Professor Daniel Muijs, School of Education, University of Manchester, has a background in educational research, particularly the analysis of large-scale datasets on school performance, again coupled with lengthy experience of teaching statistics to education students at all levels.

Dr Erica McAteer, Psychology and Human Development, Institute of Education, University of London, has a background in both psychology and educational research, and has particular expertise relating to teaching and learning within higher education, and to research capacity building.

1.1 What is modelling?

Faced with quantitative approaches to data collection and analysis for the first time, many students are inclined to wonder why such methods are necessary, and what they add to our understanding. Those who make extensive use of quantitative methods have many answers to these questions, some practical and others more philosophical in nature. However, the key answer that we want to focus on here is based on the idea that scientific approaches to investigation in any discipline including education, psychology and other fields of social research are characterized by systematic collection of data, in order to gain as clear and unbiased a picture of some aspect of the world as possible. For instance, if we want to know something about how students verbal abilities change with years of schooling, we would gather data from a representative range of students at different levels of education, using the same measures, to make sure that the information collected from each student was directly comparable to that of others.

This may not seem to be an answer as to the value of quantitative methods, but the notion of systematic data collection leads on in turn to that of systematic data processing , in which we attempt to extract some sense of the patterns revealed by our data when viewed collectively (hence the importance of direct comparability). A picture of this kind would not only describe the basic character of the phenomenon under investigation (in our example, how verbal abilities change over time, and whether the pattern is one of smooth, gradual increase or shows periods of accelerated change); it would also capture the relationship between different elements of that phenomenon (e.g., whether ability to provide explanations is related to the ability to generate ideas what we might term verbal fluency). In other words, then, what we are trying to do is to construct a model of our data, which allows us to explore its features, including those that might not be immediately evident from the raw observations themselves .

This is where quantitative methods come in. It is certainly possible to conceive of models of data that are not quantitative in character we always tend to reduce even quantitative models to verbal descriptions in order to capture and think about their meaning (see the next section). Nevertheless, models based on numbers and numerical relationships are generally more convenient in terms of their manipulability and the ease of exploring unsuspected properties. This is partly because numbers lend detachment to the process of investigation they help us to see general patterns beyond individual cases. More importantly, though, the development of statistical techniques over some 150 years means that we have a considerable range of systematic methods for extracting and exploring these patterns. It is these methods that are the focus of this book.

Quantitative methods provide us with an extremely powerful set of tools for generating and analysing data in scientific terms, therefore, but at the core of these approaches is always the idea that what we are trying to do is to build and test models of the world, as a central aid to understanding it in systematic fashion.

1.1.1 Some key characteristics of models

Quantitative research involves describing reality through numbers, in order to build models of different kinds. However, it is not possible to fully describe the complexity of the world using numerical data, nor would we want to. That is one key reason why we use models smaller-scale or stripped-down representations of reality, which reflect our understanding in focused fashion, so that we can explore it further without distraction (as far as possible) from other aspects of the world that are of less immediate interest.

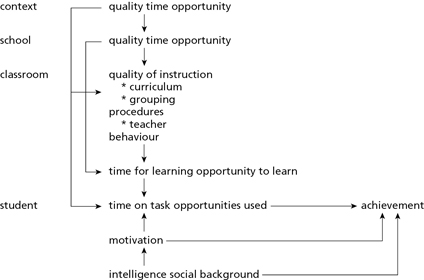

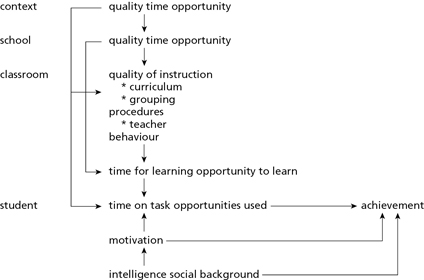

Modelling is used in a range of fields. In designing a skyscraper, architects nowadays will first develop a computer model and test that against known or estimated forces or constraints before building it. In education, we use models to try and capture the complexity of what goes on in classrooms and schools. We might, for example, want to develop a model of how school and classroom factors can influence pupil performance. An example of this is Creemers model of educational effectiveness , which attempts to capture what is known about the main factors that affect pupil achievement and how these interrelate (see ).

Figure 1.1 Creemers model of educational effectiveness, reproduced from Reezigt et al. (1999, p. 195)

Table 1.1 Classroom- and school-level factors related to the key concepts of quality, time and opportunity, reproduced from Reezigt et al. (1999, p. 196) |

Classroom level |