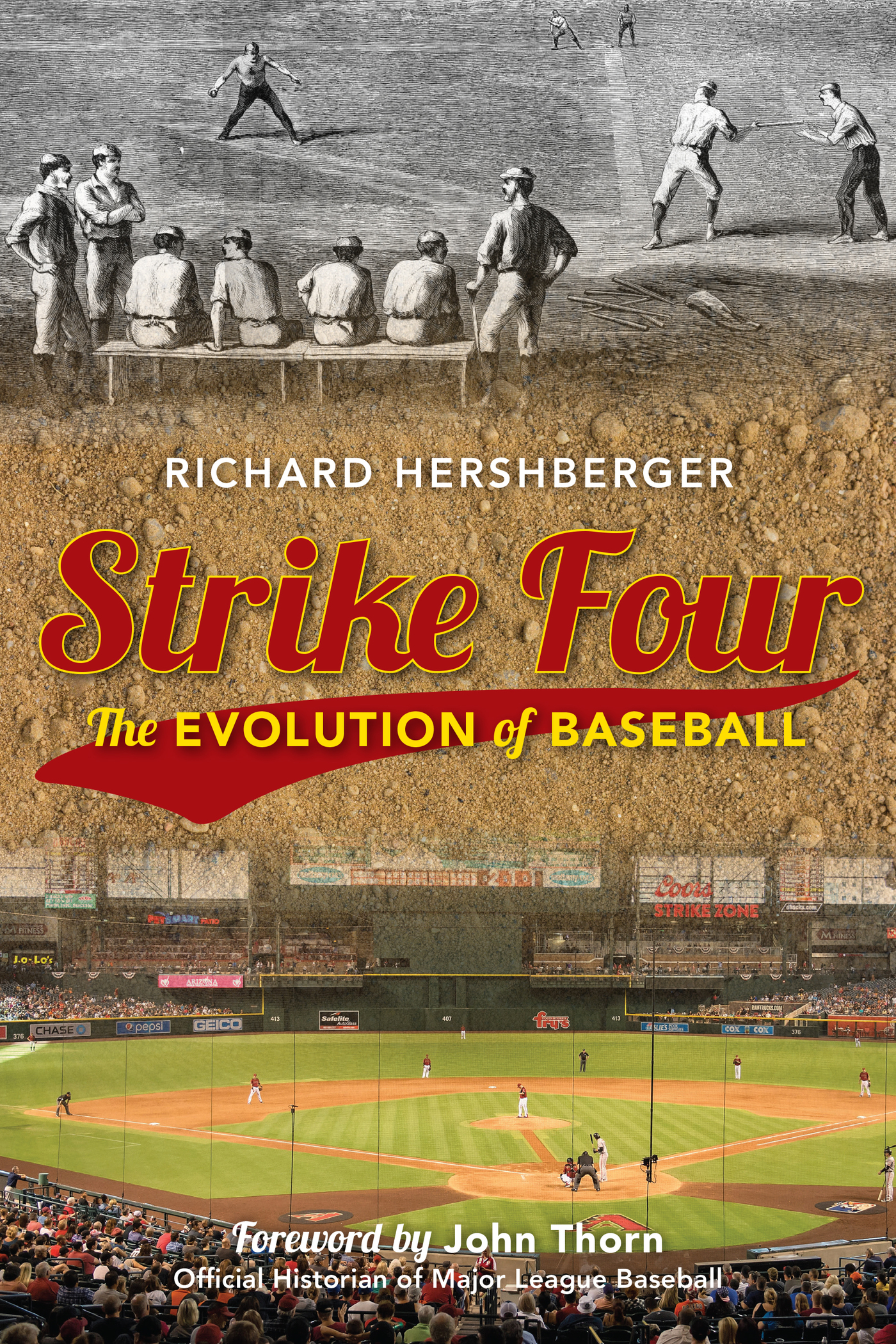

Strike Four

Strike Four

The Evolution of Baseball

Richard Hershberger

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

6 Tinworth Street, London SE11 5AL

Copyright 2019 by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hershberger, Richard, author.

Title: Strike four : the evolution of baseball / Richard Hershberger.

Description: Lanham, Maryland : Rowman & Littlefield, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018034781 (print) | LCCN 2018052194 (ebook) | ISBN 9781538121153 (electronic) | ISBN 9781538121146 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: BaseballHistory.

Classification: LCC GV862.5 (ebook) | LCC GV862.5 .H47 2019 (print) | DDC 796.357dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018034781

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

To Anne, Rebecca, and Margaret

My womenfolk

Foreword

John Thorn

Every baseball fan believes that he knows the rules of the game, and has always known them, ever since playing ball as a kid. Three strikes and youre out. Three outs and you change sides. If nine men are not available, hitting to right field might be ruled an out.

One of the great charms of baseballand the reason that so many of us become fans for lifeis its basic simplicity and slowly emerging complexity, along with its quality of fairness and balance, both in how the game is played and how its events are recorded. A run scored by one team is a run allowed by the otherin a way unmatched in real life. For nerds like me, and author Richard Hershberger, such elements of the game were and continue to be at the core of the games allure.

Why do we keep score? Because victory is important even in simulated or sublimated combat, which in large measure is what sport is about. Why do we preserve records? As the tangible remains of games contested long ago, records transform play into an artifact of culture and thus the basis of a repeatable common experiencewhich is a fine way to describe a rite or ritual. To those who say baseball is unimportant, I say it is one of the central life experiences that binds us as Americans.

The starting point for this splendidly conceived book are the rules of the 1845 Knickerbocker Base Ball Club of New York. While an earlier set of rules, recorded by William Rufus Wheaton of the Gotham Club of 1837, survived even beyond the formation of the Knicks, it was presumed to have been lost more than 150 years ago.

In 1854, the Knicks, Gothams, and Eaglesthe three principal clubs of the dayagreed to consolidate their somewhat separate understandings of how the game was to be played. This paved the way for the great convention of New York area clubs in 1857, when at last baseball was formalized as a game of nine innings; until then the first team to score 21 runs in an even number of innings was the victor. As players skills developed, particularly on defense, it became more difficult to reach 21 runs and drawn games became more prevalent, along with the ethically questionable practice of stalling for darkness so that the lesser club might play for a draw and thus attain a moral victory. In the years that followed, the called strike and the called ball were introduced so as to speed things along.

All the same, most veteran fans believe the game remains pretty much the same as it always has been, even if many complain that the game of their youth has become too long and/or too slow. As Bruce Catton noted in American Heritage in 1959:

The neat green field looks greener and cleaner under the lights, the moving players are silhouetted more sharply, and the enduring visual fascination of the gamethe immobile pattern of nine men, grouped according to ancient formula and then, suddenly, to the sound of a wooden bat whacking a round ball, breaking into swift ritualized movement, movement so standardized that even the tyro in the bleachers can tell when someone goes off in the wrong directionthis is as it was in the old days. A gaffer from the era of William McKinley, abruptly brought back to the second half of the twentieth century, would find very little in modern life that would not seem new, strange, and rather bewildering, but put in a good grandstand seat back of first base he would see nothing that was not completely familiar.

As in real life, baseballs statutes tend to lag behind evolving custom and practice: Savants and scoundrels are always seeking an edge, in a gray realm barely outside black-letter law. Movie mogul and malaprop master Sam Goldwyn once noted that a verbal contract isnt worth the paper its printed on. Maybe so, but much of how we come to agree or disagree is based upon common understandings, even if those stray from the text.

Player conduct left unfettered may descend quickly to anarchy, which was a hard sell to paying patrons of the game in the 1890s, when rowdyism was the frequently leveled charge. Yet, reins held too tightly will rankle the participants, squelch free expression, and deter innovation. There is a balance to be struck by the sachems of the game, and despite the occasional whipsaw creation and deletion of a new rule, the game and its players are undeniably better with each new generation.

Umpires, once routinely accused of favoritism and ineptitude, have become, throughout the years, more proficient, as well as more plentifulit was a long time before the leagues were willing to employ two per game. No one comes to the park hoping for an umps brilliant interpretation of the rules or the performance of his duties anyway; invisibility is the hallmark of competence.

Richard Hershberger writes of the rules with humor and a deep erudition lightly worn. While no one but he reads the rules for fun... there is no better word to describe his book about the rules. It is, if you will forgive the shopworn term, a page-turner.

Hershberger even makes bold to offer a solution, born of baseballs primordial age, for the extra-inning marathons that try fans patience and decimate pitching rotations: Revive the draw as an acceptable outcome, as it was for all the years of baseball before it came to be played under the lights. I agree.

It is now 60 years since Bruce Cattons observation that the game that was good enough in Ansons day is good for that of Trout and Betts. Baseballs rules continue to evolve in the present century, particularly with the advances in digital technology, and the day may not be far off when balls and strikes are called robotically. Speaking for myself, I hope that day does not come.

Acknowledgments

This book would never have been written were it not for the Society for American Baseball Research and its Nineteenth Century Committee creating an environment of encouragement and collegiality. No book is created in a vacuum. SABR provided the air for this one. I owe particular thanks to Cliff Blau and David Nemec for their assistance with the manuscript. They have saved me from several pratfalls. Matt Rothenberg at the Giamatti Research Center at the Baseball Hall of Fame faithfully filled in the gaps in my collection of rule books, and J. Thomas Hetrick prepared the index.

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.