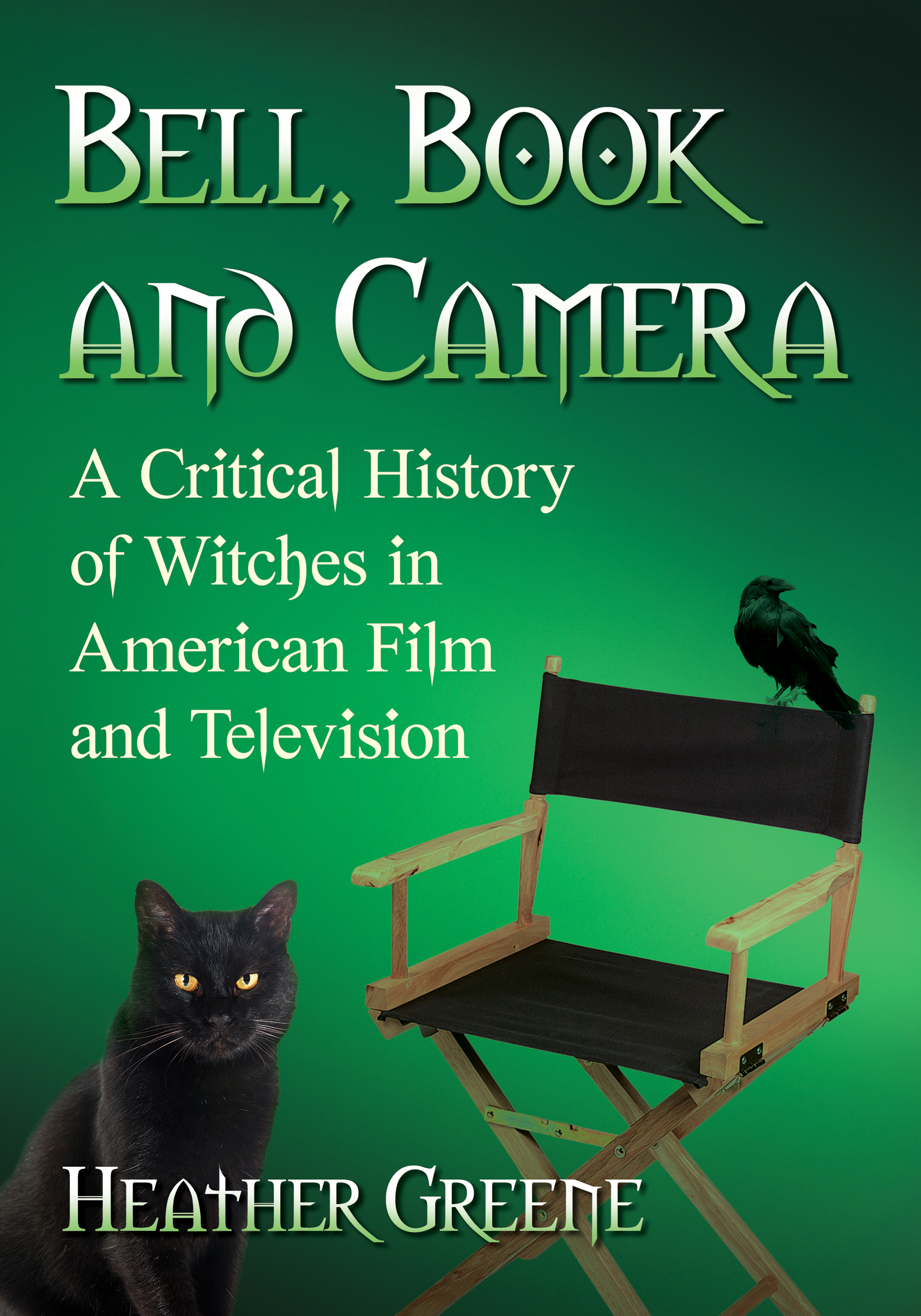

Bell, Book and Camera

A Critical History of Witches in American Film and Television

HEATHER GREENE

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-3206-3

2018 Heather Greene. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover images 2018 iStock

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

This book is dedicated to my parents,

who taught to me to always believe in magic.

And to my three wonderful children:

Magic is creating what you dream.

Dont ever stop dreaming.

Acknowledgments

There have been many people who have supported this project and allowed me the time to walk through this magical journey of cinematic witchcraft. Id like to thank, first and foremost, my family who left me alone to watch endless hours of movies and endured my non-stop chatter on the subject. Their unconditional support and love is inspiring, and can never be repaid.

Id like to also thank the administrative and writing teams at The Wild Hunt who supported this project and kept the vital news service running in my absence.

Finally, I want to acknowledge a few people who took time for personal correspondence to clarify and assist with various topics, including Thomas Doherty, Philip Heselton, Penny Cabot, Dr. Emerson Baker, Ashley Mortimer, the Rev. Selena Fox, Jason Mankey, Ed Stedman, Adam Simon, Michael Henry, Bob Sennett, Emily Uhrin, Anna Biller, Tomas Zurek, Sean Bridgeman, and Jeff Miller.

Im sure there are others. It has been a long road, and projects like this cannot be done without a team of excellent people pushing them along.

A Woman Unleashed:

An Introduction

We are the weavers, we are the web;

We are the spiders, we are the thread.

We are the Witches back from the dead.

Wiccan Chant, Shekinah Mountainwater

The word witch and what it evokes is complicated, but yet it seems so simple. The witch is a woman with a black hat, green skin, and a broom. She is a deviant mistress of the dark arts. She understands how to work with herbs and roots, and eats children for supper. The witch owns crystals, books, beads, and a black cat. She dances under the moon and cackles while stirring her brew. She is the seducer of husbands and the consort of Satan. She worships the great Goddess and loves nature. She wears a lace bonnet to church, breaks glass with her mind, and serves mousse with Tannis root. We know who she is. We recognize her.

As a child, I adored MGMs classic film The Wizard of Oz (1939). I looked forward to watching it each year when CBS aired the movie on Halloween. I was particularly fascinated with, and simultaneously terrified, by Margaret Hamiltons portrayal of the Wicked Witch of the West. I loved her loud cackle and how her cape flew as she spun dramatically in the orange-colored smoke. Over the years, as I became increasingly interested in the occult and reality-based Witchcraft, I never abandoned my childhood love of that film. To this day, after years of film study and occult study, The Wizard of Oz still remains my favorite movie of all time. While the film as a whole is undoubtedly one of Hollywoods gems, it is the Wicked Witch who ultimately stood out for me. She triggered something that I understood on a deeper levelsomething inspirational. Although clearly the antagonist, this green-skinned woman in her jet black dress depicts someone who commands her own power. She is a woman unleashed, a non-conformist, and a rebel.

Within fictional narratives, the witch is, at her most basic, a woman who lives in the space society has chosen to abandon. She practices crafts that community marks as unacceptable or that religion defines as sinful. She is the adolescent girl discovering her sexuality, the woman who commands it, and the crone who no longer needs it but still understands it. That is the witch; she is all of those things and more. At her very essence, she is the woman who knows too muchabout society, about life, and about herself. She is both the oppressed and the empowered.

In the introduction of her book The Witch in History, Diane Purkiss writes, I argue that the witch is not solely or simply the creation of patriarchy, but that women also invested heavily in the figure as a fantasy which allowed them to express and manage otherwise unspeakable fears and desires, centring on the question of motherhood and children. Purkiss statement hits on one of the central reasons I began this study. The witch archetype exists in two modes: one of oppression and one of empowerment. How is it possible that one single cultural construct can contain two strikingly different and seemingly opposed central meanings? Moreover, when and how does this meaning shift and how does it affect narrative presentations?

In her book A Skin for Dancing In: Possession, Witchcraft and Voodoo in Film, Tanya Krzywinska observes the same point, saying:

The figure of the female witch has commonly been seen in critical works on the horror film as a product of male fantasies about the otherness of womens bodies. Beyond this, the figure of the female witch in cinema has received fairly limited critical attention, and little consideration has been given to the idea that the cinematic witch is likely to appeal to a different set of fantasies specific to women.

As noted by Purkiss and Krzywinska, Western manifestations of what we know as a witch are far more complicated as the curtain is pulled back. While it would seem that her construction is wholly driven by patriarchal concepts and a very specific religious bias, the story is far more intricate. Upon closer observation, it appears that the witch archetype is not only dependent upon traditional religious or political views stemming from a male-centered eye, but she is also dependent on shifting social contexts with regard to gender politics, sexuality, demographics of reception, and even modes of storytelling, which in this discussion would be limited to cinema and television.

The witch, as a narrative character construction within Western culture, is not as fixed in her meaning as one might first think. Centuries of influence are woven into a very weighted and tangled mess of iconography and symbolic value that has modulated through belief systems, time, and cultural experience. As a result, the witch archetype exists in a type of liminal space, where she has been used and used again as both a tool of oppression and an inspiration for self-making. The Wicked Witch, for example, was for me both a source of fear and one of empowerment. I understood that she was bad but also indulged in her decisiveness and strength.

Before going forward, it is important to note that Hollywood did not re-create the wheel, so to speak. The witch archetype was already a very recognizable, fully functioning cultural icon prior to the birth of the American film industry. She came to Hollywood already loaded with a depth of meaning derived predominantly from European origins, but also from African Tradition Religions such as Vodun. More specifically, the dominant iconography found within the construction of the American narrative cinematic witch is primarily from fairy tales or folklore (e.g., Charles Perrault, Grimm Brothers, Hans Christian Andersen), classic literature (e.g., Shakespeares

Next page