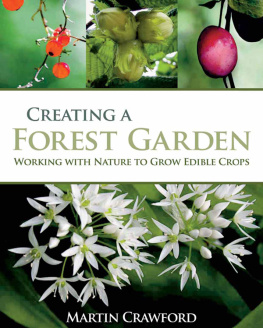

C REATING A

F OREST G ARDEN

W ORKING WITH N ATURE TO G ROW E DIBLE C ROPS

M ARTIN C RAWFORD

First published in 2010 by

GREEN BOOKS

Foxhole, Dartington

Totnes, Devon TQ9 6EB

www.greenbooks.co.uk

Martin Crawford

All rights reserved

Design & layout

Stephen Prior

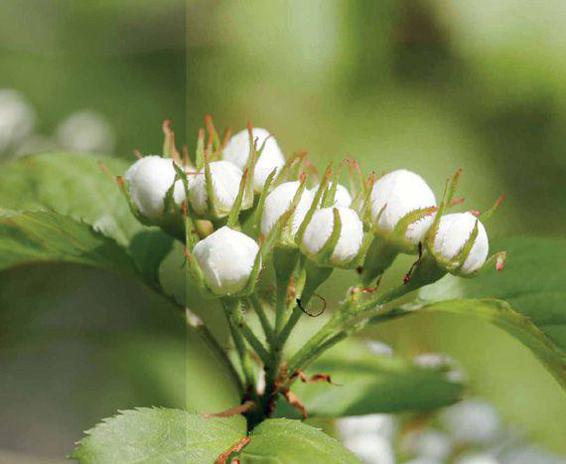

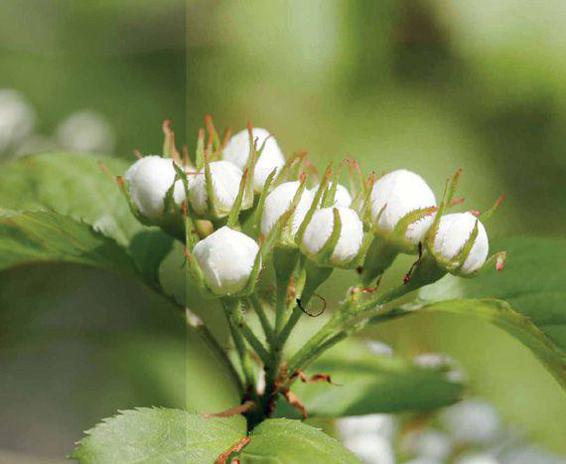

Photographs by Martin Crawford and Joanna Brown www.jozart.co.uk

(see for credits)

Illustrations by Marion Smylie-Wild

www.marionsmylie.co.uk

Disclaimer:

Many things we eat as a matter of course potatoes, beans, rhubarb, sorrel (to name but a few) are all toxic to some degree if not eaten in the right way, at the right time and with the right preparation. At the time of going to press, the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate, and if plants are eaten according to the guidance given here they are safe. However, someone, somewhere is allergic to almost anything, so if you are trying completely new plants to eat, try them in moderation to begin with. The author and the publishers accept no liability for actions inspired by this book.

Print format ISBN 978 1 900322 62 1

PDF format ISBN 978 1 907448 30 0

ePub format ISBN 978 1 907448 31 7

Acknowledgements

The journey that has culminated in this book has relied on many authors and innovators, but in particular I would like to acknowledge Miguel Altieri, Ken Fern, Masanobu Fukuoka, Robert Hart, Dave Jacke, J. Russell Smith and Eric Toensmeier.

Thanks to the Dartington Hall Trust for making land available for my forest garden and agroforestry experiments.

Thanks to Justin West for his useful comments and feedback on the manuscript, and for his challenging questions in the forest garden.

Thanks to Marion Smylie-Wild for her line drawings and to Joanna Brown for her photos.

Picture credits

All photographs in this book were taken in Martin Crawfords forest garden in Dartington. All are by Martin Crawford except those on the following pages, which are by Joanna Brown.. Back cover: middle left.

To Sandra, without whom none of this would have happened.

Contents

Foreword

In 1992, in the middle of my Permaculture Design course, about twelve of us hopped on a bus for a day trip to Robert Harts forest garden, at Wenlock Edge in Shropshire. On arrival we were greeted by the short, somewhat eccentric Mr Hart himself, who had pioneered the concept of temperate forest gardening, and who lived a rather lonely existence in what was in effect a lean-to shed in an advanced state of dilapidation, surrounded by, and seemingly sustained by, his forest garden. He seemed to live for the visits of other people to his garden an extraordinary three-dimensional jumble of trees and shrubs, many of which I had never heard of before.

In spite of his advancing years, a forest garden tour with Robert Hart was like a tour of Willy Wonkas chocolate factory with Mr Wonka himself. Look at this! Try one of these! Every tree had a story about how he had heard of it, where it came from and why he had planted it. There were very few fruits there that I recognised. Little berries, warty knobbly things, delicious-looking colourful fruits, odd-looking objects vaguely recalled from Eliza bethan fruit books a riot of colour, shape and texture.

I was surrounded by Roberts diet, hung from wildly different trees and shrubs. Here, he felt at home. Me, I felt bewildered, yet profoundly intrigued. There was something extraordinary about this garden, something that touched many of those who made the pilgrimage to Wenlock Edge. As you walked around the garden, and as you lay under the trees eating your sandwiches once the tour had finished, an awareness dawned that what surrounded you was more than just a garden. It was, like that garden that Alice in Alice in Wonderland can see only through the door she is too big to get through, a tangible taste of something altogether new and wonderful, yet also instinctively familiar.

This seeming riot of plants and trees, when explained, proved to be an intelligently designed, three-dimensional food system, based on perennial plants, which offered a whole new way of imagining agricultural systems. Above all, it created an extraordinary space with height, with colour, with scents and wildlife yet one in which one instinctively felt at home. Perhaps what Hart created was the closest to what we imagine the Garden of Eden as being. I remember being taken with the idea of a garden one could get lost in.

After Harts death, the garden was lost to the world as a working model. Over subsequent years his books, as well as the taste of what was possible that people had gained from their visits to Wenlock Edge, acted as an inspiration for thousands of such gardens around the world. Using Roberts books, and then Patrick Whitefields How to Make a Forest Garden, people began trying to replicate Harts garden many of them, as Dave Jacke and Eric Toensmeier discovered when researching their Edible Forest Gardens books, replicating Harts mistakes as much as his successes.

Martin Crawford was one of those early visitors to Harts forest garden, and since then has made the single most extraordinary contribution to our understanding of what makes a forest garden actually work. For many years, as a permaculture teacher, I have been in awe of Martins work. Here is a man who, virtually singlehandedly, runs a demonstration forest garden, a larger research site, a mail-order business, training courses and tours, and publishes a quarterly journal. I have subscribed to Agroforestry News for many years, and whenever I meet other teachers we always rave about Martins work and its extraordinary potential.

When, in 2005, I moved to Devon, just up the road from Martin, I was struck by how few people had heard of his work, which is so respected internationally. With his appearance in Rebecca Hoskings film A Farm for the Future, and now with this book, Martins vision of what food production in this country could look like, and indeed needs to be like, is starting to spread. Not before time. The challenge we need to grapple with is nothing less than this: how do we transform everything we do, including the systems by which we feed ourselves, in such a way that at the end of each day we have locked more carbon into the ground than we have emitted? To say that this calls for a rethink of many basic assumptions is to greatly understate the magnitude of the challenge. One of the key questions for farming is how to move it towards something that is diverse, robust, perennial, based not on tilling the soil but on building soil instead, and able to draw up its own nutrients and lock up carbon. It is such systems that Martin has both researched and developed, and he is an unrivalled source of knowledge on the subject.

I have waited a long time for this book, and I am delighted that you finally hold it in your hands. It is the distillation of many years of Martins work, and it offers a toolkit for forest gardeners; both novices and old hands. When I am asked to articulate a vision for the future, that vision contains urban agriculture, localised food systems, local markets and so on, but always agroforestry whether as urban fruit and nut tree plantings or as intentionally designed and abundant large-scale agroforestry. What I always point out to people is that these things are not fanciful and somehow Utopian; rather they are all things one can see working already in different places Martins demonstration forest garden on the Dartington Estate in Devon being one of the key examples. The power of Martins work is not just that it offers a vision of an abundant, post-fossil-fuel farming system, but also that it offers research to back that up, the tools for designing it, the models and even the plants themselves. And now, the definitive manual. Once one has tasted the potential of what Martin suggests in this book, one cannot look at food production in the same way again. I have nothing but the deepest gratitude for Martins work.

Next page