First published in 2010 by

GREEN BOOKS

Foxhole, Dartington

Totnes, Devon TQ9 6EB

www.greenbooks.co.uk

Reprinted 2010 and 2012 with minor amendments

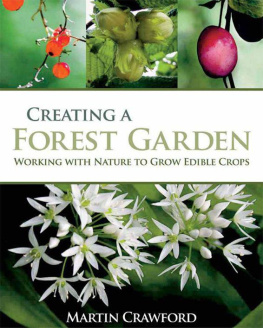

Martin Crawford

All rights reserved

Design & layout

Stephen Prior

Photographs by Martin Crawford and Joanna Brown www.jozart.co.uk

(see page 6 for credits)

Illustrations by Marion Smylie-Wild

www.marionsmylie.co.uk

Print edition ISBN 978 1 900322 62 1

PDF format ISBN 978 1 907448 30 0

ePub format ISBN 978 1 907448 31 7

Disclaimer

Many things we eat as a matter of course potatoes, beans, rhubarb, sorrel (to name but a few) are all toxic to some degree if not eaten in the right way, at the right time and with the right preparation. At the time of going to press, the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate, and if plants are eaten according to the guidance given here they are safe. However, someone, somewhere is allergic to almost anything, so if you are trying completely new plants to eat, try them in moderation to begin with. The author and the publishers accept no liability for actions inspired by this book.

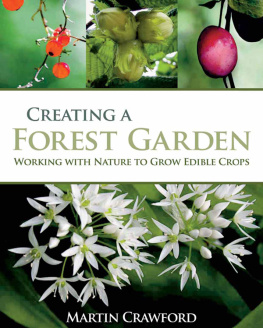

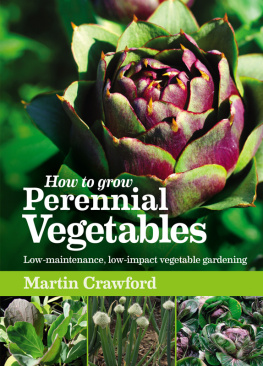

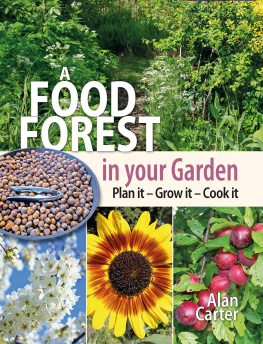

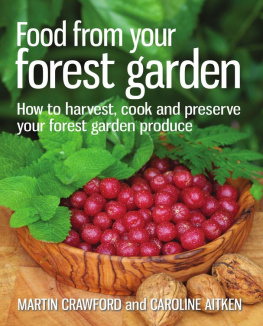

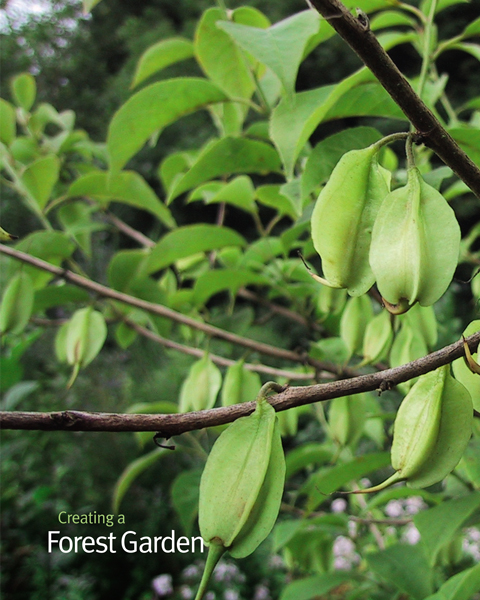

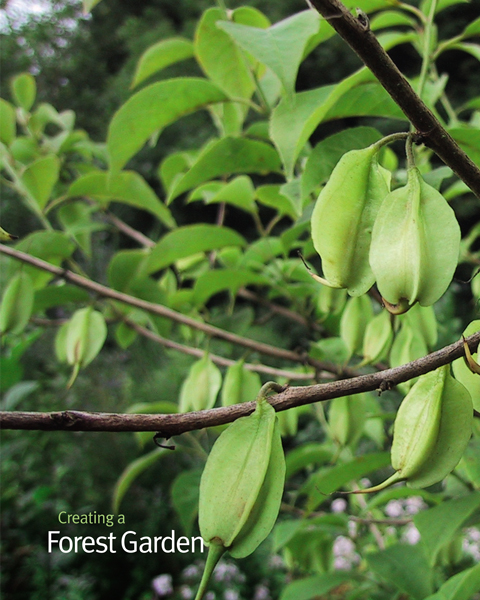

Cover and preliminary page images

Front cover: Top left: redcurrants (Ribes rubrum). Top centre: hazelnuts (Corylus avellana). Top right: plum (Prunus domestica) Purple Pershore. Bottom: ramsons (Allium ursinum). Back cover: Top: heartnuts (Juglans ailanti folia var. cordiformis). Centre: honey bee on apple blossom. Bottom: new shoot of fishpole bamboo (Phyllostachys aurea). Page 1: snowbell tree (Halesia carolina). Page 2: autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata). This page: hawthorn (Crataegus pinnatifida var. major) Big Golden Star. Page 8: cones of stone pine (Pinus pinea).

Acknowledgements

The journey that has culminated in this book has relied on many authors and innovators, but in particular I would like to acknowledge Miguel Altieri, Ken Fern, Masanobu Fukuoka, Robert Hart, Dave Jacke, J. Russell Smith and Eric Toensmeier.

Thanks to the Dartington Hall Trust for making land available for my forest garden and agroforestry experiments.

Thanks to Justin West for his useful comments and feedback on the manuscript, and for his challenging questions in the forest garden.

Thanks to Marion Smylie-Wild for her line drawings and to Joanna Brown for her photos.

Picture credits

All photographs in this book were taken in Martin Crawfords forest garden in Dartington. All are by Martin Crawford except those on the following pages, which are by Joanna Brown. 4/5, 12, 16, 24, 26, 27, 40, 49, 50, 76, 88, 97, 98, 107, 117, 119 bottom left, 122 top left, 131, 141, 146, 158 top right, 159, 172, 178, 183, 185, 191 top right, 194, 211 bottom left, 212, 213, 217 bottom right, 224 bottom right, 229, 236, 237, 243, 247, 252 bottom right, 253, 254, 269 bottom left, 276, 287, 290, 296, 302, 305, 307, 320. Front cover: top left & top right. Back cover: middle left.

To Sandra, without whom none of this would have happened

Foreword

In 1992, in the middle of my Permaculture Design course, about twelve of us hopped on a bus for a day trip to Robert Harts forest garden, at Wenlock Edge in Shropshire. On arrival we were greeted by the short, somewhat eccentric Mr Hart himself, who had pioneered the concept of temperate forest gardening, and who lived a rather lonely existence in what was in effect a lean-to shed in an advanced state of dilapidation, surrounded by, and seemingly sustained by, his forest garden. He seemed to live for the visits of other people to his garden an extraordinary three-dimensional jumble of trees and shrubs, many of which I had never heard of before.

In spite of his advancing years, a forest garden tour with Robert Hart was like a tour of Willy Wonkas chocolate factory with Mr Wonka himself. Look at this! Try one of these! Every tree had a story about how he had heard of it, where it came from and why he had planted it. There were very few fruits there that I recognised. Little berries, warty knobbly things, delicious-looking colourful fruits, odd-looking objects vaguely recalled from Eliza bethan fruit books a riot of colour, shape and texture. I was surrounded by Roberts diet, hung from wildly different trees and shrubs. Here, he felt at home. Me, I felt bewildered, yet profoundly intrigued. There was something extraordinary about this garden, something that touched many of those who made the pilgrimage to Wenlock Edge. As you walked around the garden, and as you lay under the trees eating your sandwiches once the tour had finished, an awareness dawned that what surrounded you was more than just a garden. It was, like that garden that Alice in Alice in Wonderland can see only through the door she is too big to get through, a tangible taste of something altogether new and wonderful, yet also instinctively familiar.

This seeming riot of plants and trees, when explained, proved to be an intelligently designed, three-dimensional food system, based on perennial plants, which offered a whole new way of imagining agricultural systems. Above all, it created an extraordinary space with height, with colour, with scents and wildlife yet one in which one instinctively felt at home. Perhaps what Hart created was the closest to what we imagine the Garden of Eden as being. I remember being taken with the idea of a garden one could get lost in.

After Harts death, the garden was lost to the world as a working model. Over subsequent years his books, as well as the taste of what was possible that people had gained from their visits to Wenlock Edge, acted as an inspiration for thousands of such gardens around the world. Using Roberts books, and then Patrick Whitefields How to Make a Forest Garden, people began trying to replicate Harts garden many of them, as Dave Jacke and Eric Toensmeier discovered when researching their Edible Forest Gardens books, replicating Harts mistakes as much as his successes.

Martin Crawford was one of those early visitors to Harts forest garden, and since then has made the single most extraordinary contribution to our understanding of what makes a forest garden actually work. For many years, as a permaculture teacher, I have been in awe of Martins work. Here is a man who, virtually singlehandedly, runs a demonstration forest garden, a larger research site, a mail-order business, training courses and tours, and publishes a quarterly journal. I have subscribed to Agroforestry News for many years, and whenever I meet other teachers we always rave about Martins work and its extraordinary potential.

When, in 2005, I moved to Devon, just up the road from Martin, I was struck by how few people had heard of his work, which is so respected internationally. With his appearance in Rebecca Hoskings film

Next page