To Gabriel and Daniel,

who help me keep everything in perspective

Science and art share a common mandateto find surprise in the ordinary by seeing it from an unexpected point of view.

Howard Bloom

My mother meant well. Never compare yourself to others, she taught me. Itll do nothing but bring you misery. I see her point, but comparing ourselveswhether to other people or to other thingsis what we humans do. We compare; we contrast. We sift and segregate, then order, analyzing similarities and discovering differences. Thats why we have eyes, ears, taste buds, nerve cells, brains: to compare ourselves with things larger or smaller, faster or slower, hotter or cooler. Through comparisons we create our understanding of the incredibly complex world around us, we realize aesthetic beauty, and we structure our societies.

When you compare two things, you create a duality: this or that, zero or one, black or white. But compare four, or eight, or sixteen things, and you begin to find spectrumsranges, or continuums from this to that, a bit darker or lighter, a tad louder or more quiet. The more careful your observation, and the more sensitive your tools of measurement, the better you can gaugeand engage withyour environment.

My religion consists of a humble admiration of the illimitable superior spirit who reveals himself in the slight details we are able to perceive with our frail and feeble mind.

Albert Einstein, physicist

I attempt, in this book, to provide a sense of scale across six spectrums with which we interact every day: numbers, size, light, sound, heat, and time. Certainly, there are many more spectrums we could exploredensity, weight, chemical concentration (which we can sense through smell and taste), and so onbut these six are among the best understood in science and, themselves, represent a good spectrum of our everyday experience. True, in the process of discovery, well find that we must compare ourselves with others, but rather than misery, I believe well find awe, astonishment, and a sense of humility.

I use the plural spectrums instead of spectra for a reason: While both are correct, the latter has unfortunately gained the supernatural connotation of ghosts and spirits. Although spectrum , spectra , spectral , and specter all derive from the Latin word for vision, we often apply them to phenomena that have nothing to do with what we can see. This is similar to how, over the last century, a number of words with roots in sciencesuch as dimension , evolution , and even energy have expanded their meanings far beyond their original intention. Today, the word spectrum indicates virtually any broad range of characteristics or ideas.

Human Scale In his classic novel The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy, Douglas Adams tells the tale of a massive fleet of alien spacecraft that attack Earth, only to discover that they have made a critical error in scale just before landing in a park and being eaten by a small dog. While none of us (I hope) is planning an interplanetary invasion, the lesson remains valid: Its crucial that we constantly evaluate our own perspectives and assumptions as we interact with the world.

Unfortunately, we tend to base our sense of reality on our own human scale and ignore the invisible and often surprisingly nonintuitive worlds beyond. As the biologist Richard Dawkins notes, Our brains have evolved to help us survive within the orders of magnitude of size and speed which our bodies operate at. Were comfortable within these realms, which Dawkins calls the middle world... the narrow range of reality which we judge to be normal, as opposed to the queerness of the very small, the very large and the very fast. The middle world encompasses distances easily walked, times and durations within our average life span, and temperatures more or less within the range we experience here on Earth, from ice to inferno.

No doubt its crucial to consider these human scales in the fields of architecture, ergonomic design, retail, and entertainment. But for millennia, weve intuited that there is something more, beyond our senses, both greater and deeper. The idea that we live in a somewhat muted middle world inspired both shamanic traditions and many of our greatest myths. The ancient Greeks and Hindus described us as sandwiched by worlds above and below, which are populated by gods and demons. The Christian and Nordic theologies told of realms to which we middle-worlders aspire (or fear), just beyond our mortal veilworlds higher and lower, transcendent and immanent.

And true enough, as we look through microscopes, we find worlds within worlds, realms that explain our everyday rules of physics and biology, but in which, amazingly, those same rules dont always apply. As we peer through telescopesnot just at visible light, but also at the invisible wash of X-rays, gamma rays, and microwaves that we can detectwe discover a universe grander, and weirder, than anything we had imagined.

Science has led us to realize that there is far more outside our human scale than within it, and there is actually very little in this universe that we can feel, touch, see, hear, or possibly even comprehend. The vast range of phenomena around us boggles the mind. Its not an easy task to stretch our imagination to encompass both billions of years and billionths of seconds, or trillions of atoms and trillionths of a meter. And yet, we must explore all these spectrums to gain perspective on our place in the universe.

Spectrums, Everywhere Spectrumsnot just the physical spectrums discussed in the chapters that follow but also the very concept of spectrums in generalare useful for far more than just analyzing the world in which we live. Spectrums allow us to communicate our insights and desires, no matter how mundane, with others.

If youre trying to describe a color to a graphic designer, for example, you might explain, yellow, a bright sunshiny yellow like a pound of butter. In that one phrase you invoke two spectrums: hue and brightness (or, technically, frequency and amplitude). Each spectrum is like a model, or a map, that reflects a dimension of the world around us or within us. So if you hear a specific note played on a piano or violin, you can probably imagine another tone a little higher or lower. Sip your coffee and you viscerally know it would taste better if it were warmer. These daily comparisons may seem minor, but the fact that we can build internal maps like this, often extrapolating beyond the ranges of our own personal experience, is an amazing example of what the human mind can do.

Of course, even tiny bacteria show their preferences, or fundamental tendencies, based on simple comparisons between more or less acidic environments. But as life becomes more complex, the more you can name spectrums, or categories, and the more you can name differences in those spectrums, the more you can comprehend, communicate, and thrive. After all, would you rather draw with a box of eight crayons or the jumbo 64-pack?

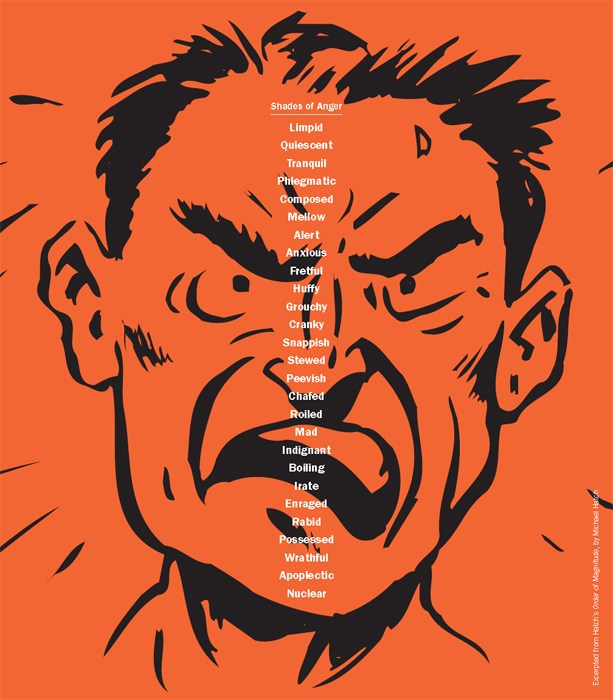

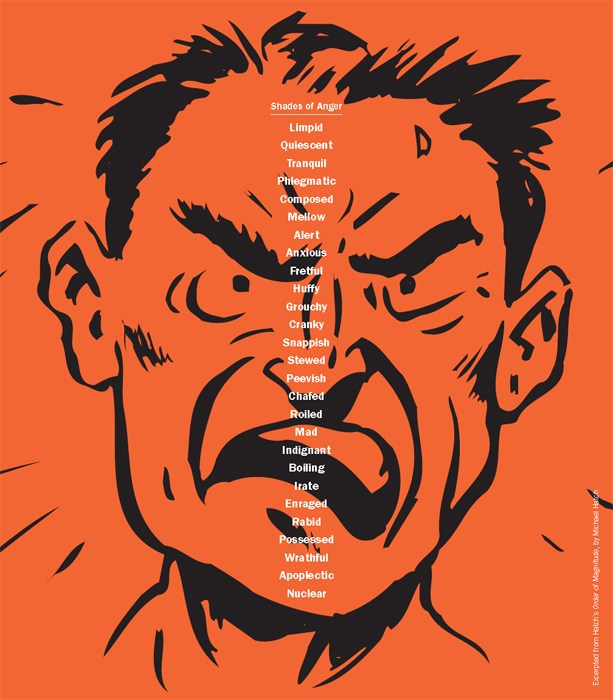

These spectrums can describe far more than physical measurement; we can use them to describe personal values and aesthetics, too. Any psychologist will tell you that if youre trying to explain how angry you are, its more helpful to say Im about an eight on a scale of one to ten than to insist on the binary Im angry or Im not. The same rule applies, of course, to sports competitions such as Olympic ice dancing, where judges rate technical ability and style against an agreed-upon spectrumeveryone has an intuitive understanding of the difference between a 7.4 and a 7.8; one is just

Next page