THE NEW NATURALIST

THE SEA COAST

by

J. A. STEERS

PROFESSOR OF GEOGRAPHY

AND PRESIDENT OF ST. CATHARINES COLLEGE

IN THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE

TO

James and Grace

EDITORS:

JOHN GILMOUR M.A.V.M.H.

SIR JULIAN HUXLEY M.A. D.Sc F.R.S.

MARGARET DAVIES M.A. Ph.D.

KENNETH MELLANBY C.B.E. Sc.D.

PHOTOGRAPHIC EDITOR:

ERIC HOSKING F.R.P.S.

The aim of this series is to interest the general reader in the wild life of Britain by recapturing the inquiring spirit of the old naturalists. The Editors believe that the natural pride of the British public in the native flora and fauna, to which must be added concern for their conservation, is best fostered by maintaining a high standard of accuracy combined with clarity of exposition in presenting the results of modern scientific research. The plants and animals are described in relation to their homes and habitats and are portrayed in the full beauty of their natural colours, by the latest methods of colour photography and reproduction.

CONTENTS

THE RELATION OF THE COAST TO THE GENERAL STRUCTURE OF GREAT BRITAIN

THE MOVEMENTS OF BEACH MATERIAL

EROSION AND ACCRETION EVIDENCE OF COASTAL CHANGES

THE COAST IN PROFILE AND PLAN

CLIFF SCENERY

SAND AND SHINGLE SPITS, AND SALT MARSHES

MAJOR SHINGLE STRUCTURES

STUDIES IN THE EVOLUTION AND SETTING OF OUR COASTAL SCENERY

EVIDENCES OF ELEVATION AND DEPRESSION OF COASTLINES

THE STORM OF 1953 AND ITS AFTERMATH

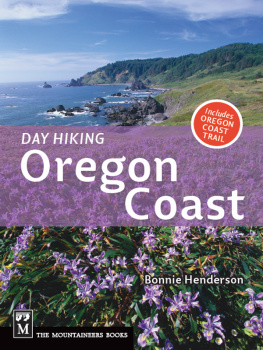

S OMEWHERE in the heart of the Midlands of England is a spot which can claim to be the most distant in these islands from the sea. Yet the distance from the nearest tide water is less than 70 miles. If the sea is a part of every Britons natural heritage, then the sea coast is doubly so; and it must be rare to find an inhabitant of the British Isles of mature years who has never seen the sea. Another volume in the New Naturalist series has disclosed the richness of the flora of our coasts and that wealth in plants is due in large measure to the great variety of coastal habitats. The British coasts have indeed everythingfrom towering cliffs rising several hundred feet sheer from deep water to mud flats a mile or more wide uncovered by every tide; from restless shingle spits and moving sand dunes to granite headlands which see little change in a century. How is it that along some stretches, despite all the efforts of man, the sea succeeds in gnawing away several feet of land a year, only to throw back the discarded material a few miles away? In this book Professor Steers seeks to explain, as far as the present state of knowledge will permit, how the varied types of coastline have been evolved and how the changes still taking place provide such a remarkable range of differing conditions for plant and animal life.

Now Professor of Geography and President of St. Catharines College, in the University of Cambridge, and previously Dean and Tutor of his College, his special field of study has been the evolution of coasts and coastlines. His studies took him early to the Great Barrier Reefs and to the cays of the West Indies, but these expeditions were but holidays from the long continued detailed studies of the Norfolk coastresulting in a book devoted exclusively to Scolt Head Island. When the Ministry of Town and Country Planning was set up he was commissioned by the Minister to make a comprehensive survey of the whole coastline of England and Wales. The lengthy report which resulted provides the essential basic information on which policies of coastal preservation and development can be based. When this was completed Professor Steers undertook a similar survey of Scottish coasts. As a natural consequence he became a member of The Nature Conservancy and so retains a continuing interest in work which must of necessity be greatly concerned with the natural history of coastal lands.

Clearly no-one is better qualified to write on the Sea Coast, and in this book we believe he has successfully combined a clear exposition of what we know, with an indication of the many directions in which the amateur observer can help in the elucidation of outstanding problemsin the true tradition of the field naturalist.

T HE E DITORS

T HERE ARE many ways of studying the coast of a country. In this book the approach is physiographicalthat is to say a study of coastal scenery in relation to its origin. This is a vast subject, and cannot be treated fully in a volume of this size, nor by one author. The proper understanding of the coast must be the result of the combined research of workers in several subjectsincluding geography, geology, ecology, and botany. In the meantime it is perhaps worth while for someone to try to give a comprehensive picture and to call attention to some of the ways in which our knowledge of the coast needs augmenting. I can only make two claims to do this; first I love the coast, and secondly it has been my good fortune to see the whole of the mainland coast of Great Britain and by far the greater part of that of the adjacent islands. This experience has emphasized only too clearly how impossible it is for any one person adequately to deal with so big a subject!

In this volume there are three main themes: (1) A brief synopsis of the relation of coast to the structure of the country and a summary analysis of the physical agencies working on the coast; (2) a discussion of the nature of different types of coastal scenery; and (3) a short account of the evolution of parts of our coastline. The final chapter on raised beaches and submerged forests is conveniently treated by itself, but its subject matter is relevant to all the other chapters.

So far as I am aware no one has attempted to deal physiographically and in some detail with the whole coast of Scotland. To do so at this stage would, I think, be difficult, much as the subject deserves it. This is so for several reasons. First of all a great deal more local work is required on specific problems and places. The interesting and extensive dunes of Aberdeenshire are now for the first time being studied. The Machair of the Western Isles, the Ayres of Orkney and the numerous saltmarshes all demand attention. Extremely little has been written about the cliffed coasts of Scotlanda study involving the relation of structure to marine erosion and other factors along miles of interesting and beautiful coast, and presenting problems for many workers. The investigation of raised beaches and associated phenomena has hardly begun in the sense of explaining how they were cut and the human uses to which they are now put. Moreover, the actual sequence is not always quite clearwhere, for example, does the pre-Glacial beach of Islay, Colonsay, and the Treshnish Isles fit? Perhaps the controvery concerning the origin of fiords is settled, but there is still scope for much work on the local differences in form of the western sea-lochs. Still more important, and this applies to England and Wales with equal force, is the examination and mapping of the topography of the adjacent sea floor. The full study of a coast must depend a great deal on a knowledge of the adjacent submarine floorand yet how little is this matter discussed in many coastal studies in which its introduction would be highly relevant!