Table of Contents

Introduction

Drawing Out the Dragons

JAMES A. OWEN

When I get a little money I buy books; and if any is left I buy food and clothes.

ERASMUS

That quote by Desiderus Erasmus is usually mentioned, wryly, by someone who doesnt share Erasmus point of view about someone who does. Im so far in the latter category I cant even see the other side. I am utterly addicted to print, and am physically incapable of passing a newsstand, bookstore, or secondhand shop without giving the books on display at least a cursory glance. More often than not (which means practically every single time) I make some kind of a purchase, and for a moment that new book might as well have been under a Christmas tree for all the love I foster on it.

To a lot of people, it might seem as if my priorities are a bit skewedbut Im really just engaging in something as old as humanity itself: Im searching for connections to everything and everyone around me. And buying books is the best way I know to do that because books, and more precisely stories, are as important and vital and essential as food and clothesand Im not entirely convinced about the clothes.

Stories are what bind us together as families, and communities, and cultures. Stories are what connect us to our past, anchor us in our present, and lay the groundwork for the future. Stories are how we communicate understanding to one another both literally and through metaphor. And as one essayist in this collection noted, stories are important because none of them are new. All stories have already been toldonly our point of view changes. And it is that unique point of view that makes every story at once individual and collective. Our differences make us interestingbut our similarities make us family. And that brings me to the storyand storiesof Christopher Paolini.

It was the stunning blue-visaged dragon painted by John Jude Palencar that first caught my attention. Ive always considered myself an artist who writes rather than the other way around, so it was the design of the book jacket for Eragon that drew my eye before I cared one iota about reading the book itself. It wasnt until the next book Eldest, with its matching red dragon, appeared that I really paid attentionand still, it wasnt to read the books, but to take note of an interesting cultural trend: dragons were cool.

Not that dragons hadnt always been coolbut usually they were cool to a subset of fans of a genre (fantasy) that most people considered, well, juvenile. So when a book set firmly within that genre was marketed to that exact audience (juvenile readers) to amazing and continuing success, dragons suddenly became cool to people who had never liked them before, or who had but didnt realize it until Eragon came along. It was icing on the cake that the author of this literary fireball was himself barely old enough to drive. And suddenly, everyone in the world seemed to be reading books with dragons on the covers.

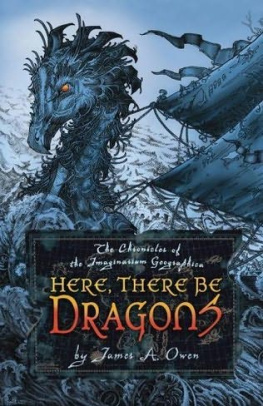

Having been one of that previous subset of readers, I already knew dragons were cool, which was one of the reasons I had written and drawn a book called Here, There Be Dragons. But it can only be chalked up to happy convergence (rather than astute planning) that my book (featuring a dragon on the cover, colored blue at the request of my publishers sales and marketing department) happened to be published just as the Eragon movie promotions were getting underway and every bookstore worthy of the name was assembling displays of books featuring dragonsincluding mine.

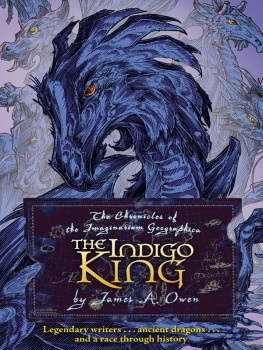

(The fact that Owen and Paolini sit next to each other alphabetically has resulted in a running joke among booksellers that I owe Chris dinner any time he asks, since he helped sell so many of my books. This became less of a joke and more of a potential accounting concern when my second book, The Search For The Red Dragon, appeared with a [naturally] red dragon on the cover. I would like to state for the record that there was espionage, research, and prayer involved in planning to make my next book, The Indigo King, purple so it would not match up with the gold cover of Brisingr, Chriss third book. At the rate were already selling, though, Im going to be picking up his dinner tab until hes forty.)

My love for the cover art aside, it became a matter of professional courtesy to read the books and discover for myself just what all the hubbub was about. So I did. And amidst the thrilling tales of dragons and elves and heros journeys I found something else in Christopher Paolinis booksI found myself.

A lot has been made about Paolinis relative youth, to which I can relate. I was writing, drawing, and publishing my own comic books at the age of sixteenand while I did not enjoy the same early and vast success nor endure the same harsh scrutiny that he has had to grapple with at such a tender age, I can empathize to a degree that many others cannot. I was the youngest publisher to ever exhibit at the San Diego Comic-Conand I was constantly questioned, not because of my professionalism or the quality of my work, but because of my age. Had he been less persistent and not gotten the publishing deal he did, or had his books not been so commercially successful, Paolini might well have had an easier time of it. Under the glare of so much scrutiny, even praise has a certain kind of weight, because with success comes expectations, and life is difficult enough at fifteen without being world-famous to boot.

But whatever else critics might question, the achievement itself, to have written (and published) so young, is worthy of note. It requires an innate maturity to be able to convey so much in a work of fiction when one has had relatively less life experience. (It should also be notedand is utterly appropriatethat two of the finer essays in this collection are written by authors who are as young [or even younger] now as Paolini was when he first conceived Eragon.)

The story itself is one that has been both lauded and criticized as not new. More than one essayist touches on this concept, that Paolini has drawn upon well-known and well-used archetypes for both character and plot. Paolinis detractors claim that the work is therefore merely derivative, and brings nothing new to the world of fiction. But his advocates (of which I am one) maintain that he has simply done what all the great authors have done before him: retold the stories common to us all from a unique point of view. And it is a point of view that has been embraced by millions upon millions of readers around the world.

The question has been posed whether the story of Eragon is also the story of Christopher Paolini. I maintain that it might bebut the same can be said of us all, writers and readers alike. We write to express how we see things to the rest of the world, and we read to try to make sense of the world around us. Both are efforts to communicate, to make connections with the larger Story. Our dragons are metaphors, used to tie together the things we know and the things we hope to understand. Readers may find themselves drawing close to Eragon or Saphira, or perhaps Roran, and in the process discovering something about themselves. Its been no different for any other story thats gone before, whether its a tale of Perceval or Gilgamesh or even Luke Skywalker. They are all the same story. They are all our story. And the tales told in the Inheritance Cycle are our stories, too, told as they are by a storyteller who understands this, and put them into words in the way he believes they should be told.