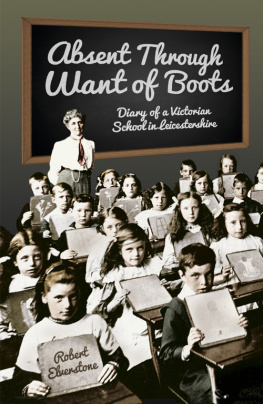

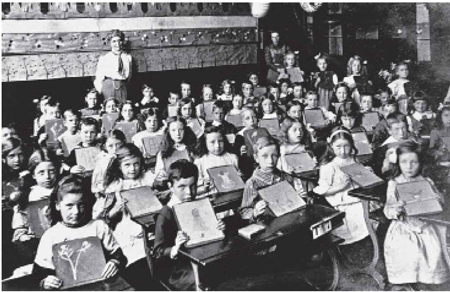

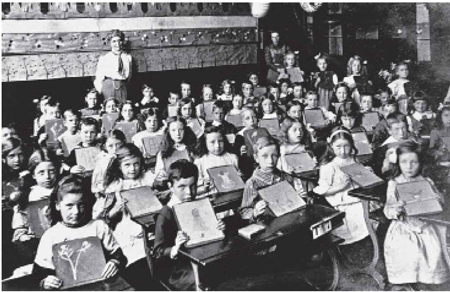

Class , Hinckley Board School.

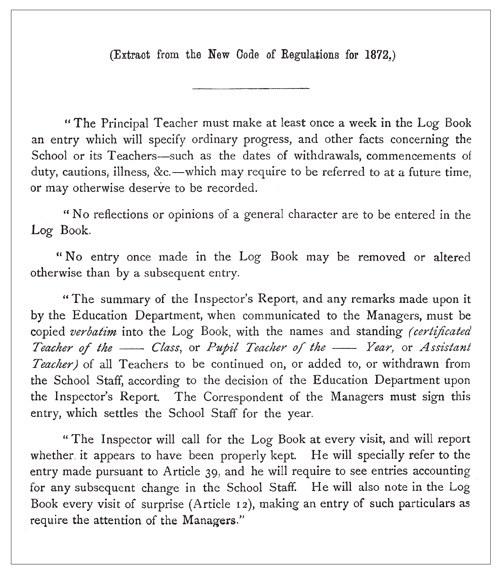

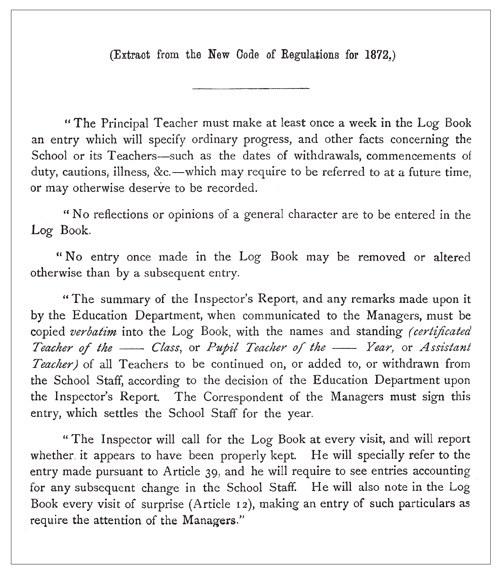

The New Code of Regulations for 1872 required the Principal Teacher to make an entry in the logbook at least once each week.

I am extremely grateful to Lesley Hagger, Director of Children and Young Peoples Service in Leicestershire, for granting permission to transcribe extracts from the logbooks of the Hinckley Board Schools.

Many thanks to Mrs Cath Allison, head teacher of Holliers Walk Primary School, for allowing access to the books, and to Maggie and Michaela for ensuring their care and survival!

Thank you to the staff of the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland for their help and support in tracking down information, and especially to Jenny Moran, Senior Archivist (Access and Information), for granting permission to include extracts from the logbooks held in the county collection.

Thanks also to the staff at Chilvers Coton Heritage Centre in Nuneaton for permission to take photographs of their classroom, especially to Rob Everitt for the guided tour. It was very much appreciated.

Many thanks to my wife Julie for help with the pictures and illustrations and for putting up with the hours of research and editing.

A big thank you to all the staff, pupils and parents with whom I had the enormous pleasure to work with for over thirty-five years at this school. And for those whose journey in education is just beginning, especially Eloise and Lizzie, school days are some of the most important in your life. so make good use of them!

Finally, sincere thanks to Mr R.D. Brookes, without whose inspiration this book would never have got started.

All photographs and illustrations, unless otherwise indicated, are attributed to and remain copyright of the author. Every attempt has been made to trace copyright and apologies to anyone I may have inadvertently missed.

Contents

one |

two |

three |

four |

five |

six |

seven |

eight |

nine |

ten |

W hen Queen Victoria ascended the throne in 1837 , education was, at best, an ad hoc affair. Whereas wealthy families could afford to pay for private education, for most of the population schooling was dependent on geographical location and the generosity of local benefactors.

In the early nineteenth century, Sunday schools, charitable schools and ragged schools had all attempted to provide a basic education for children from poorer families.

By 1851 , over , National Schools had been opened by the Church of England. British Schools provided a similar education for children of Nonconformist families.

Some children attended a local Dame School, but there was no formal system of education and no standards by which childrens progress could be measured. Neither was there any requirement that children should attend school, many families and employers preferring to keep children working and earning money.

The 1870 Education Act was the first Act of Parliament to pave the way for a compulsory system of National Education for all. The Act placed the responsibility of providing suitable accommodation and teachers firmly in the grasp of local, elected Boards. These schools were known as Board Schools.

The Act gave elected Boards the power to pass by-laws to enforce full-time compulsory education at a local school for all children between the ages of and , and for half-time attendance for children up to age thirteen. Boards could charge children d per week and had the power to prosecute parents who did not ensure the attendance of their children.

School Boards were obliged to ensure there were enough school places for all children in the local area. In Hinckley, this meant the provision of new, purpose-built accommodation.

Victorian schools were generally of red-brick construction with high ceilings. Windows were placed well above the height of children to prevent them being distracted by looking outside. Large rooms to accommodate the children were divided into smaller spaces by hanging curtains.

Each classroom was equipped with a free-standing blackboard and wooden desks placed in rows. Boys and girls were seated separately and, in some schools, in separate classes with their own entrance. The walls would be plain brick, possibly with a poster of Queen Victoria and a map of the British Empire displayed. The teacher would have a desk at the front facing the children. A regime of strict discipline was maintained.

Younger children would each have a slate or sand-tray on which to write. These could be wiped clean and re-used. Older children would write with a pen which was dipped in ink. Left-handed children would be forced to use their right hand to prevent the ink from being smudged.

Class sizes were often huge, up to children in a single class not being uncommon. Because of this, lessons often required copying from the blackboard, rote learning and repetition. Children would be asked to memorise poems, lists of British monarchs and multiplication facts.

Children were able to pass standards which determined which class they were in. With little or no understanding of children with additional needs, this often meant that much older children would find themselves labelled as a dunce and put in a class with much younger children.

Lessons consisted of reading, writing and arithmetic. Once each week an object lesson would take place. The teacher would introduce an object to the classroom and then initiate discussion. In the early days of education, this is as near as most children would ever come to a science lesson.

Boys and girls were taught differently. In addition to basic lessons, girls would be taught needlework while the boys went off to do woodwork. Boys were also taught marching skills, often by a local retired drill sergeant.

Many teachers were unqualified and trained on the job. Children, on leaving school at thirteen, could apply to become pupil teachers. This was a kind of apprenticeship. Pupil teachers received daily lessons from the head teacher. Each year, pupil teachers were examined to see if they could progress to the next year. After five years, these teenagers then qualified as uncertified teachers or assistants. It wasnt until 1946 that government policy required all teachers to be qualified.

Some schools used a monitor system. These were generally older children who assisted the teacher in the classroom. Monitors received additional lessons after school which they would then teach to a small group of younger children the following day. Children who acted as monitors often went on to become pupil teachers.

The school day usually began at nine oclock with the ringing of the school bell. A midday break was long enough to allow children to go home for dinner and then return in the afternoon. The school day generally finished around half past four or five oclock.

Children in Hinckley often came from very poor families and, especially in the winter months, were inadequately clothed. The logbooks refer to children being cold or not attending due to poor weather. Particularly in deep snow, some children were marked as absent through want of boots.

Next page