LIFE IN

A VICTORIAN

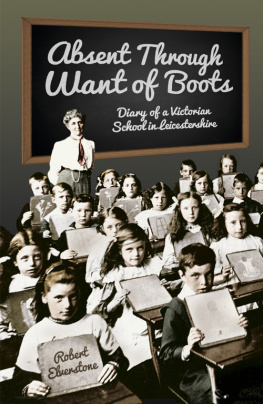

SCHOOL

PAMELA HORN

Pitkin Publishing

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

Text Pitkin Publishing, 2013

Written by Pamela Horn. The right of the Author, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Edited by Gill Knappett

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5619 2

Original typesetting by Pitkin Publishing

C ONTENTS

I MPORTANT D ATES

1808 Establishment of the non-sectarian Royal Lancasterian Association (later the British and Foreign School Society) to promote elementary schooling.

1811 Establishment of the National Society for the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church (usually shortened to the National Society) the main school provider pre-1870.

1833 First state grant of 20,000 is made for elementary education.

1833 The Factory Act states that working children aged 9 to 13 must attend school for 2 hours daily, increasing to 3 hours in 1844.

1839 The first two of Her Majestys Inspectors of Schools are appointed.

1846 Introduction of the teachers certificate examination.

1862 The Revised Code for elementary education introduced, initiating the payment by results system and annual examinations.

1870 Elementary Education Act designed to provide a school place for every child.

1870 National Union of Elementary Teachers established.

1880 Compulsory attendance at school for children aged 5 to 10, and thereafter to 13.

1891 Free elementary education becomes available; a government grant of 10s (50p) a year is payable for each pupil in a public elementary school.

1893 Minimum school leaving age raised from 10 to 11.

1899 Establishment of the Board of Education to superintend matters relating to education in England and Wales.

1899 Minimum school leaving age raised to 12, although in some agricultural districts 11 is still accepted.

A N E LEMENTARY E DUCATION

E ducation in Britain can be traced back to Roman times; great institutions such as the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge were developed in the 13th century; and by the time Henry VIII was on the throne a wider emphasis was being placed on education for privileged boys. In Scotland an Act of 1696 stated that each parish should provide a school building and finance a teachers salary, but it was not until Victorian times that provision was made in England and Wales for every child both boys and girls to have an elementary school place, whatever their background. New buildings were constructed, changes made in educational administration, and comparisons drawn with developments in other European countries. As a result, literacy rates improved. When Queen Victoria ascended the throne in 1837, when the population of Britain numbered around 18 million, only just over two-thirds of all men marrying and just over half of the women could sign their name rather than having to make a mark; by 1901, the year of the Queens death, more than nine out of ten of her subjects could sign their name when they married.

The content and scope of the schooling provided gradually extended and compulsory education was introduced for elementary school pupils between 1870 and 1880. This revealed the special needs of some children, such as the poor diet of pupils from deprived areas and the difficulties experienced by blind, deaf, and physically and mentally disabled children. The first tentative steps were taken to remedy these.

Older middle- and upper-class children, too, had a greater range of schools available to them and a wider curriculum developed to meet the countrys growing professional and commercial needs. But it is the children from ordinary families, who attended elementary schools, where the changes had the biggest effect on Victorian Britain. When W.E. Forster, Vice-President of the Education Department, introduced the 1870 Elementary Education Bill in the House of Commons, he said: Upon the speedy provision of elementary education depends our industrial prosperity. It is of no use trying to give technical teaching to our artisans without elementary education and if we leave our work-folk any longer unskilled, notwithstanding their strong sinews and determined energy, they will become over-matched in the competition of the world. Upon this speedy provision depends also, I fully believe, the good, the safe working of our constitutional system.

S CHOOLS FOR THE M ASSES

T he early aim of Victorian schools was to instil religious principles and moral values into the pupils. Religious instruction, and sometimes lessons in reading and writing, was something the Sunday Schools had sought to achieve for working-class children from the late 1700s but with limited success, given their restricted finances, inexperienced teachers and the limited time pupils attended. They did have the virtue, however, of being free, which did not apply to most elementary day schools. In addition they did not disrupt any work plans the children might have.

But while religion was important, throughout the Victorian era the general organization of schooling was essentially class-based, designed to fit children for the station in life into which they had been born. This affected all aspects of their school life, from the curriculum they followed to the length of time they attended, and the age at which they were expected to leave.

The general philosophy was expressed in 1867 by Robert Lowe, a former Vice-President of the Committee of Council on Education (in effect an Education Minister) when he declared: The lower classes ought to be educated that they may appreciate and defer to a higher cultivation when they meet it, and the higher classes ought to be educated that they may exhibit to the lower classes that higher education to which, if it were shown to them, they would bow down and defer.

DAME SCHOOLS

The lack of a firm moral and religious message led to doubts about the role of the many small private dame schools which had been set up by a variety of so-called teachers. Dame schools usually run by elderly women, and sometimes men, of varying abilities also offered instruction, especially to young children, but most were conducted in cottage rooms by a teacher who combined her schooling with domestic chores. In 1871 it was reported that 53-year-old Maria Busbys school in Chelsea, London, was attended by eight boys and two girls, who were taught in Mrs Busbys kitchen, while she was carrying on mangling. One girl, aged over 7, could read and another child could write, but clearly the education offered was minimal. Parents may have chosen it for its informality and its childminding service, and were willing to pay the weekly fee of 4d or 5d (2p) she charged, rather than seek out a more efficient school.