By the same author

Victorian Farm with Alex Langlands & Peter Ginn

Edwardian Farm with Alex Langlands & Peter Ginn

Wartime Farm with Alex Langlands & Peter Ginn

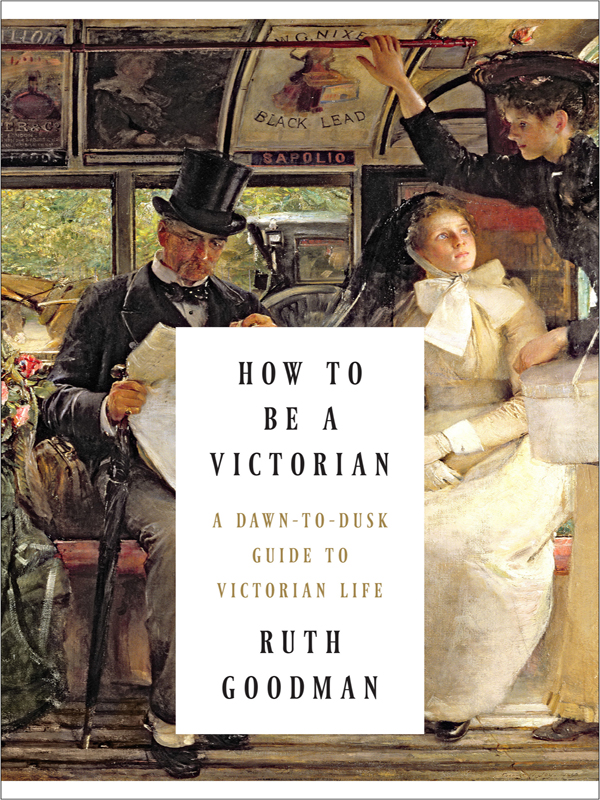

How to Be a Victorian

A Dawn-to-Dusk Guide to Victorian Life

RUTH GOODMAN

LIVERIGHT PUBLISHING CORPORATION

A Division of W. W. Norton & Company

New York London

To all those who persuaded me to step forward into the nineteenth century

Copyright 2013 by Ruth Goodman

First American Edition 2014

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Penguin Books Ltd.

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Production manager: Anna Oler

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Goodman, Ruth, 1963

How to be a Victorian : a dawn-to-dusk guide to Victorian life / Ruth Goodman. First American edition.

pages cm

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Penguin Books Ltd.T.p. verso.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-87140-485-5 (hardcover)

1. Great BritainSocial life and customs19th century. 2. Great BritainHistory Victoria, 18371901. 3. Great BritainSocial conditions19th century. I. Title.

DA533.G557 2014

941.08--dc23

2014023719

ISBN 978-0-87140-853-2 (e-book)

Liveright Publishing Corporation

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

Contents

I want to explore a more intimate, personal and physical sort of history, a history from the inside out: one that celebrates the ordinary and charts the lives of the common man, woman and child as they interact with the practicalities of their world. I want to look into the minds of our ancestors and witness their hopes, fears and assumptions, no matter how apparently minor. In short, I am in search of a history of those things that make up the day-to-day reality of life. What was it really like to be alive in a different time and place?

History came to life for me as a hobby, but once that spark was lit it quickly became a passion and, finally, a profession. From the very start, an element of practical experimentation has been key to the way I try to understand the past. I like to put time and effort into studying the objects and tools that people made and used, and I like to try methods and approaches out for myself.

Take, for example, a dark wool coat lying in a drawer at a small museum in West Sussex. Heavily worn and lined with a patchwork of fabrics, it belonged to a farm labourer and dates back to the 1880s. The coat reminds us that here was a man who sweated and left stains on his clothes, who physically felt the cold and whose wife spent hours carefully and neatly sewing up the tear still just visible on the right-hand side, next to the buttons. When I look at that careful repair, Im reminded of the sewing textbooks in use in Victorian schools for working-class children. A trawl through the bookshelves leads to a set of instructions, accompanied by beautifully drawn diagrams. With needle and thread in hand, I can attempt to follow these instructions on a tear in one of my own garments. His wife was evidently well trained (particularly if my own struggles are to be noted). Questions spring forth. How widespread was such needlework education, and was it likely to have been women who carried out such repairs? If it takes me over an hour to do the work, would my Victorian forebears have been quicker? When would they have fitted such a chore into their day?

Such intimate details of a life bring a feeling of connection with the people of the past and also provide a route into the greater themes of history. As a tear in a mans coat can lead one to question the nature of mass education, or to look into the global nature of the textile industry, so too the great sweeps of political and economic life bring us back to the personal. The international campaign against slavery and the American Civil War would, in combination, have devastated the trade in cotton, driving weavers back into hunger. This would have pushed up the price of the labourers coat, making that repair more necessary.

Queen Victorias reign spanned more than sixty years and encompassed vast social, political and economic changes. Industries rose and fell and scientific revolutions overturned the old understanding of how the world worked. Peoples ideas of right and wrong were challenged, and legislation was dragged along in the wake. With all these different things going on, how, then, can one talk about what it was like to be a Victorian?

This book is my attempt. It is a personal exploration, following my own fascinations, questions and interests. There is much that I have missed, and there are many excellent books that relate in more detail the political, economic and institutional shifts of the period. I aim to peer into the everyday corners of Victorias British subjects and lead you where I have wandered in search of the people of her age.

I have chosen to move through the rhythm of the day, beginning with waking in the morning and finishing with the activities of the bedroom, when the door finally closes. Where I can, I have tried to start with the thoughts and feelings of individuals who were there, taken from diaries, letters and autobiographies and expanding out into the magazines and newspapers, adverts and advice manuals that sought to inform and shape public opinion. Glimpses of daily life can be found in items that people left behind, from clothes to shaving brushes, toys, bus tickets and saucepans. More formal rules and regulations give a shape to the experience of living, from the adoption of white lines to mark out a football pitch to the setting of a standard of achievement for school leavers.

In this hunt for the ordinary and the routine I have tried to experience elements of the life myself. Many of these experiences came when I spent a year on a Victorian farm, and later some time at a pharmacists shop, over several television series. Others have come as part of my own ongoing explorations: testing recipes, making clothes, following hygiene regimes, whittling toy soldiers. All these experiences have been useful, if not always successful, and have helped me frame questions and think more critically about what the evidence is telling us. Ultimately, there is also a degree of empathy and imagination involved. Let us begin then, with imagining ourselves waking up at the end of a Victorian night.

It began with a shiver. Rich or poor, in city dwelling or farm labourers cottage, the first step out of bed was likely to leave you cold. The wealthier classes often had coal fireplaces and iron grates in their bedrooms, but these were rarely lit. Jane Carlyle, the wife of Scottish essayist Thomas Carlyle, lived in a fashionable London town house in the 1850s (see Plate 8). Despite her familys income, fires were only prepared upstairs at desperate times, when bedrooms were used by the sick. Once, when a fire was indeed lit for her at a wealthy friends home, she described it as a wanton luxury, one that made her feel quite guilty about her own robust good health.

Next page